Table of Contents

Maricopa County, Arizona: Where press freedom goes to die

Rob Schumacher / The Republic / USA TODAY NETWORK

Clint Hickman, Maricopa County Board of Supervisors vice chairman, makes comments about the integrity of the 2022 election during the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors meeting in Phoenix on Nov. 16, 2022.

Late last Friday, FIRE filed an amicus curiae — “friend of the court” — brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, asking it to protect journalists’ right to cover the recently concluded 2022 midterm elections in Maricopa County, Arizona. If it doesn’t, county elections officials will go back to blocking journalists they don’t like from important press conferences, in violation of the First Amendment.

After finding themselves at the center of a national debate over alleged election fraud in the 2020 presidential election, Maricopa County elections officials wanted to tamp down negative coverage of their election oversight. So in September 2022, they implemented a press pass regulation that blocked journalists from election press conferences if they showed “conflicts of interest” and were not “free of associations that would compromise journalistic integrity or damage credibility.”

If you’re confused by what those terms mean, you’re not alone — they’re vague enough to empower county officials to make viewpoint-based decisions on which outlets can and cannot attend press conferences.

As FIRE’s brief explains, government officials can disagree with or express dislike for their critics, but the government “crosses a constitutional line when government officials cite that prior criticism as grounds to restrict press access.”

During the 2022 midterm elections, county officials used that rule to deny press conference access to Jordan Conradson, a reporter for online news site The Gateway Pundit, one of the most prominent proponents of claims that Maricopa County officials engaged in or ignored election fraud. After the denial, Conradson and The Gateway Pundit sued for press access, but lost in district court. Despite acknowledging the press regulation raised “thorny questions” and relied on “fraught consideration[s],” the court held it was a neutral attempt to regulate “journalistic integrity.”

Conradson and The Gateway Pundit filed an emergency appeal to the Ninth Circuit, which granted them temporary press access while the case is pending. FIRE filed an amicus brief in support of their appeal.

As our brief argues, government actors violate the First Amendment when they create arbitrary standards that enable them to discriminate against viewpoints they dislike:

The Press Pass Regulation’s standards for determining objectivity are so malleable and undefined that they grant officials unbridled discretion to deny press passes based on whether they think a journalist’s prior reporting is accurate, regardless of so-called objectivity. Granting government a free license to determine what makes a “good” journalist and then allowing it to exclude “bad” journalists based on the content of their prior journalism violates the rule that “[t]he government may not discriminate against speech based on the ideas or opinions it conveys.” Iancu v. Brunetti, 139 S. Ct. 2294, 2299 (2019).

The risk of viewpoint discrimination is particularly high when government officials try to gatekeep press access based on whether a journalist is sufficiently “objective” or “truthful.” That’s because truth is often in the eye of the beholder, especially when it comes to politics. What’s more, almost 50 years ago, the Supreme Court held the government can’t force newspapers to be objective, because the First Amendment protects their right of “editorial control and judgment.”

Here, Maricopa County officials did even worse than create an arbitrary regulation. They actually used it to ban Conradson because they didn’t like his political reporting. County officials testified that they blocked his press pass because, in their opinion, his work was “poorly sourced, researched, and reported,” and because he used “inflammatory and/or accusatory language, such as ‘Fake News Media,’ ‘globalist elitist establishment,’ and ‘highly flawed 2022 Primary Elections.’”

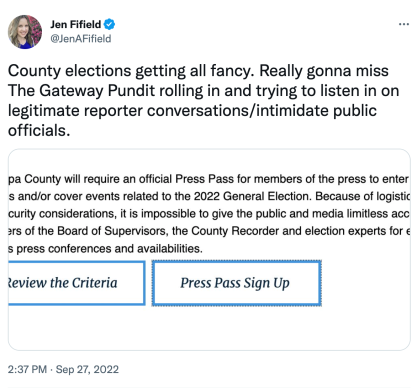

The top elections official in Maricopa County, Stephen Richer, even retweeted the tweet below, implying his endorsement that the press pass regulation was implemented specifically to exclude The Gateway Pundit and Conradson (his retweet has since been deleted):

As FIRE’s brief explains, government officials can disagree with or express dislike for their critics, but the government “crosses a constitutional line when government officials cite that prior criticism as grounds to restrict press access.” Here, Maricopa County officials abused their regulatory power to exclude a critical reporter and his publication. Whether or not you agree with Conradson’s views on the election or his reporting style, that abuse of power violates the First Amendment. That’s true whether it’s Maricopa County officials excluding The Gateway Pundit or the president of the United States kicking disfavored reporters out of his press room. FIRE urges the Ninth Circuit to quickly reverse.

You can read more about the case and view FIRE’s full brief here.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

Australian regulator wants to dictate what the whole world can see online

Montgomery College student and faculty groups’ film screening canceled just minutes after college president’s 11th hour condemnation

Don’t turn commencement season into cancellation season