Table of Contents

80 years ago the Supreme Court introduced ‘Fighting Words’

Eighty years ago today — on March 9, 1942 — the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire that “fighting words” was a category of unprotected speech. The Court unanimously determined that Walter Chaplinsky, a Jehovah’s Witness, uttered such words at a marshal who arrested him under a breach of the peace law.

Chaplinsky allegedly had been proclaiming the virtues of his religion on the public streets of Rochester, New Hampshire — which displeased others. At some point, Chaplinsky cursed a local marshal as a “God-damned racketeer” and “damned fascist.”

This led to Chaplinsky’s arrest under a broadly worded New Hampshire law that provided “no person shall address any offensive, derisive, or annoying word to any other person.”

Today, such a law would be considered overbroad, but in 1942, the New Hampshire Supreme Court had limited the law, writing that it applied only to “fighting words.” On appeal, the Supreme Court accepted this term and narrow construction. Writing for the Court, Justice Frank Murphy explained:

There are certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem. These include the lewd and obscene, the profane, the libelous, and the insulting or “fighting” words — those which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.

Not only did Justice Murphy define fighting words, but he also uttered what would become the most famous (or infamous) and oft-cited passage in American jurisprudence for the principle that the First Amendment does not protect all types of speech. In other words, there are some narrow, unprotected categories of speech that do not receive First Amendment protection.

Walter Chaplinsky was arrested and punished for criticizing a local government official.

An important facet of modern First Amendment jurisprudence is a gradual narrowing of these unprotected categories of speech. For example, there used to be obscenity prosecutions for booksellers who sold novels by James Joyce and D.H. Lawrence. Now, obscenity is relegated to an occasional prosecution of someone who traffics in very violent hardcore depictions of sexual conduct.

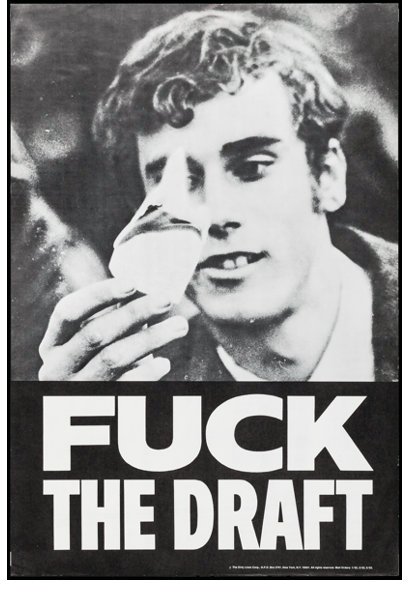

The same narrowing has occurred for fighting words. In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently struck down convictions based on the fighting words rationale and limited the doctrine. Most notably, the Court limited “fighting words” to direct, face-to-face personal insults in Cohen v. California (1971), ruling that Paul Robert Cohen did not utter fighting words when he wore a jacket bearing the message “Fuck the Draft” in a Los Angeles County courthouse. Justice John Marshall Harlan II explained in his majority opinion that Cohen’s jacket was not a “direct personal insult.”

The Court also reversed a fighting words-type conviction in Lewis v. New Orleans (1974), ruling that the New Orleans ordinance that prohibited the use of “obscene or opprobrious language” toward police officers was too broad. In a concurring opinion, Justice Lewis Powell reasoned that police officers, because of their enhanced training, are expected to exercise greater restraint than the average person.

Years later, the Court ruled that government officials cannot engage in viewpoint discrimination under an ordinance that targets only certain types of fighting words. Justice Antonin Scalia explained in R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul (1992) that city officials had “no such authority to license one side of a debate to fight freestyle, while requiring the other to follow Marquis of Queensberry rules.”

Critics contend that the doctrine is unsound. Professor Burton Caine, in his impressive piece, “The Trouble with the Fighting Words Doctrine: Chaplinksy v. New Hampshire is a Threat to First Amendment Values and Should be Overruled,” calls the doctrine a “tragedy for the jurisprudence of Freedom of Speech.” Caine explains that “what the Court in Chaplinsky labels as fighting words is, in reality, ‘political’ speech or speech on public issues, which deserves the utmost protection in the American democracy.”

For example, Walter Chaplinsky was arrested and punished for criticizing a local government official. The essence of the First Amendment, its shining principle, is that individuals should have the freedom to criticize the government.

The U.S. Supreme Court has invalidated convictions based on the fighting words doctrine. However, the concept remains part of First Amendment law.

Caine, Mark P. Strasser, and others have also noted that the U.S. Supreme Court has invalidated convictions based on the fighting words doctrine. However, the concept remains part of First Amendment law and has been used by many lower courts to uphold convictions for breach of the peace or disorderly conduct decisions.

As I explain in “The Fighting Words Doctrine: Alive and Well in the Lower Courts” for The New Hampshire Law Review, key factors in fighting words cases include whether the speech is coupled with aggressive conduct, whether the volume of the speech is loud or more subdued, whether there is a single foul utterance or a string of profanities, whether the recipient of the communication is a police officer or an average citizen, and whether the speech includes racial slurs.

I conclude that the “doctrine remains a vibrant and controversial part of First Amendment law.”

And it all started eighty years ago today.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

No, the Berkeley Law student didn’t have a First Amendment right to interrupt the dean’s backyard party

Salman Rushdie calls out left-wing censorship in CBS interview

Falsely claiming a First Amendment right at a dinner party at private home — FAN 419.1