Table of Contents

John McWhorter’s ‘Nine Nasty Words’ is my May book of the month — with a serious digression into academic freedom & teaching about epithets

Key Concept — Use-mention distinction: The philosophical difference between using a word and mentioning it. E.g. the sentence “That is a blue bike.” uses the word “blue,” while the sentence “The sign read ‘Blue bikes rule’.” only mentions the word “blue.” In the context of slurs, the use-mention distinction holds that mentioning a slur when discussing it or quoting accurately is not morally equivalent to calling someone a slur.

Because I did my Excessively Prestigious book of the year last month, I had decided not to have a May book award, but one spectacular May release made me change my mind.

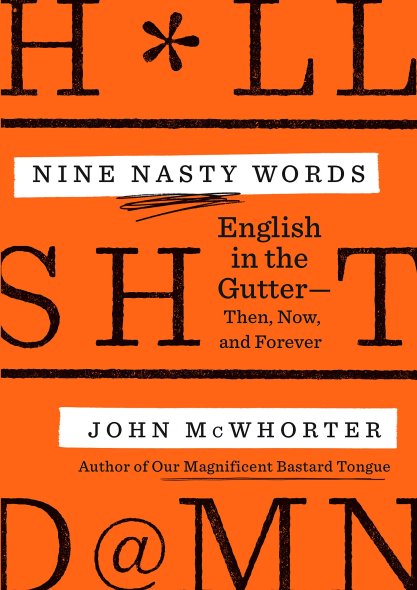

The Prestigious Ashurbanipal Award: “Nine Nasty Words: English in the Gutter: Then, Now, and Forever” by John McWhorter

One of the delightful things about being a father of small children is watching their natural sense of language in action. Sometimes they come up with formulations for grammar or invent new words that are intuitively correct, and even express ideas we can’t express easily. For example, my five-year-old truly believes the word “hidive” (pronounced “hi-div”) is a word for being very good at hiding. He explains with otherwise perfect grammar which insects are very “hidive.” Even better, my three-year-old likes to state what is on his mind when he has a particular feeling, leading to the formulation “I am thirsty about water,” “I am hungry about apples,” and “I am lonely about mommy.”

As a First Amendment lawyer married to a speech-language pathologist, we come at speech from different angles, but those interests intersect at the amazing lexicographical work of John McWhorter.

While I hesitate to say it, his new book on profanity, its history, its myths, and where it comes from in evolution is an utter delight. (I will get to why I hesitate a bit later.)

In this book he covers nine words (close your eyes and close the tab if you can’t abide cussing) and includes the classics: shit, fuck, bitch, motherfucker, and more. The book is filled with wit, insight, and historical analysis that makes use of everything from notes scrawled by monks in the margins of 16th-century illuminated manuscripts to a potty-mouthed underground stag record by blues singer-songwriter Lucille Bogan to early cartoons, including a mildly foul-mouthed Porky Pig.

I cannot do the scope, scale, and precision of the book justice, but I must share with you an excerpt about the great Dorothy Parker that will stay with me forever:

Dorothy Parker wrote theater reviews early in her career, which were just as funny as anything she wrote or said later, and in 1922 included a comment on one justly forgotten trifle: “If I were to tell you the plot of the piece, in detail, you would feel that the only honorable thing for you to do would be to marry me.”

It has also left me dying to know more about the “Flip the Frog” cartoon, to see Peter Shaffer’s play “Lettice and Lovage,” and to introduce him to my wife to talk about the brilliant show “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend.”

But why am I hesitant to say I’m delighted by it?

Because I’m afraid it will be misread. Because he touches on a radioactive topic: the etymology of racial epithets.

While these have always had outsized power throughout my life, they have become even more taboo in just the past few years. Society’s tolerance for these slurs has developed nuance over the years, with most vilified when directed at individuals, yet generally accepted in popular culture when used by in-groups. But until recently, there was a shared understanding that when you put your scholarly hat on to talk about particular epithets, or quote literature or case law, that use was not inappropriate. Indeed, you can’t read case law or histories without encountering these words, used in ways that violate current norms. It was understood that accurately quoting the word or uttering it in discussion was different than hurling the word as an insult. In other words, the “use-mention distinction.”

But there have been efforts in recent years to collapse the use-mention distinction and to treat any utterance of a slur regardless of context as not only worthy of criticism, but as requiring sanctions up to and including loss of employment.

I first ran into this in the case of Donald Hindley at Brandeis in 2007, and at the time I considered it one of the worst cases I’d ever seen. In that case, he was explaining and condemning the slur “wetback.” Hindley was investigated, punished for “harassment,” and monitored in his classroom. Eventually Brandeis revoked the punishments but kept the harassment finding. That was the start; since then, cases like this have become extremely common, and more egregious.

Since the beginning of 2020, FIRE has investigated 105 cases involving potential punishment for both using but mostly mentioning racial epithets, most commonly the n-word. An unusual number of those cases involve what would historically have been viewed as academically-protected speech:

- In March 2020, Emory University ended a year-long investigation into law professor Paul Zwier, who used the n-word when discussing a racial discrimination case in class, and again during his office hours when defending his decision to do so. FIRE wrote to Emory in January 2019, calling on the institution to defend academic freedom.

- In June 2020, Central Michigan University fired journalism professor Timothy Boudreau for refusing to promise he would never again invoke the n-word in class, after a former student posted a year-old, nine-second video of Boudreau teaching a First Amendment class about the Matal v. Tam case, which overturned a federal ban on slurs in trademarks. FIRE represented Boudreau in a case which was ultimately settled.

- Also in June 2020, UCLA investigated political science lecturer (and former Air Force pilot) Lt. Col. W. Ajax Peris for reading from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” which recounts the use of racial slurs. FIRE wrote to UCLA asking it to uphold its obligations as a public institution bound by the First Amendment.

- In October, Duquesne University terminated education school professor Gary Shank for using the n-word in a class discussing how its use is broadly deemed inappropriate. FIRE wrote to the Department of Education about this, noting that Duquesne appeared to be misrepresenting its program to the public (and its accreditor) by promising academic freedom and free expression rights it did not provide.

- In January, the University of Illinois at Chicago suspended law professor Jason Kilborn for having, in a prior semester’s Civil Procedure exam, asked a question with a racial discrimination fact pattern in which the following text appeared verbatim: “. . .managers expressed their anger at Plaintiff, calling her a ‘n____’ and ‘b____’ (profane expressions for African Americans and women) and vowed to get rid of her.” FIRE wrote to UIC, but the investigation continues.

- In April, Georgetown University opened a formal bias complaint against American government professor Michele Swers who read the n-word out loud when quoting from the Brandenburg v. Ohio decision, which set out the “imminent lawless action” test. FIRE wrote to Georgetown calling on the school to recognize it could not punish Swers without violating its speech promises. The school seems to have silently closed the investigation.

While cases like these are not new, the frequency with which they happen — and the reluctance of professors to go public with them — has increased.The failure to respect the use-mention distinction may ironically deprive students of some of the most important voices in the battle for civil rights.

In 2014, Jeannie Suk Gersen noted that anxiety over violating Title IX was convincing some professors not to teach the law of sexual assault. Now, the anxiety over racial slurs has led to professors facing adverse administrative action for having taught the works of James Baldwin; Mark Twain; Martin Luther King, Jr.; and the Supreme Court of the United States. Where this ends is anyone’s guess, but in the meantime, the failure to respect the use-mention distinction may ironically deprive students of some of the most important voices in the battle for civil rights.

But back to John McWhorter’s book: If you love words, you will love the “Nine Nasty” ones — and more — the author presents for examination. I especially recommend listening to the audiobook because hearing McWhorter explain it himself makes it that much more fun. I only regret that he couldn’t get the rights to my “My Gallant Crew, Good Morning” from H.M.S. Pinafore so he could sing it to the listeners. (A fact he laments.)

The Prestigious Fats Waller Award: ‘Hamilton’

The “Hamilton” soundtrack.

I know. I am pushing for a popular production again.

But this is inspired by John McWhorter’s love of musicals. When I met him for the first time, I had just seen it and was blown away, and we went on to gush about our favorite musicals together.

But I must say it was kind of interesting to see that when it got to the small screen (Disney+) and everyone could watch it, the expectations built could never be met. People thought it was going to be much more than a musical could ever be, as it’s been so romanticized in praise and in exclusive environments.

So what did listeners get? I had one friend who was disappointed that it wasn’t particularly innovative hip-hop. My response was that it was incredibly innovative musical theater, about as good as it gets, and one of the most important musicals in history. And it might even be just a little bit patriotic as well.

The Prestigious Jack Kirby Award: The ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’ musical episode (S6:E7), “Once More, With Feeling”

Yes, I know I’ve already made the series as a whole one of my picks, but I want to emphasize the Buffy musical episode (Season 6: Episode 7, if you’re looking for it) in particular. It’s better if you’ve seen the whole series and not bad if it’s all you ever see. I find myself asking where else will you hear a vampire croon, “If my heart could beat it would break my chest”?

Next up: In June’s awards, perhaps the LEAST surprising choice for the Prestigious Ashurbanipal Award in our short history!

Disclaimer: John McWhorter joined FIRE’s Board of Directors this year, but I was a fan of his work years before, and I couldn’t allow his affiliation with us to stop me from honoring his work. And, yes, I am extremely excited for his next forthcoming-in-October book (yes, two books in one year!), “Woke Racism: How a New Religion has Betrayed Black America.”

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

BREAKING: New Title IX regulations undermine campus free speech and due process rights

Stanford president and provost cheer free expression in open letter to incoming class