Table of Contents

Political tolerance, academic freedom, and support for faculty free expression

A recent data snapshot published by the American Association of University Professors draws on data from the General Social Survey and concludes that American public opinion about higher education may be related to ideological differences in attitudes toward academic freedom. Survey data on how the general public views academic freedom and controversial scholarship is fairly scant, so the exploration of the topic is certainly a welcome one. Yet, even though the conclusion is plausible given the analyses reported, it is grounded in some curious analytical decisions.

First, although the GSS is a long-running survey of American public opinion and is frequently employed to analyze changes in social attitudes over time, the questions analyzed in the data snapshot are considered measures of political tolerance and may only tangentially measure people’s attitudes toward academic freedom.

Second, the analyses exclude two of the controversial figures the GSS asks about: a homosexual and a Muslim clergy member preaching hatred of the United States. Excluding these figures from the analyses underestimates the overall tolerance for controversial figures and masks a good deal of agreement between liberals and conservatives on who should be allowed to speak, teach, and keep a book in the public library.

The final point is a methodological one: A good deal of scholarship on political tolerance contends that the method employed by the GSS to measure tolerance of controversial figures may conflate affinity with tolerance and as a result suggests the use of an alternative method. Each of these points is discussed in more detail below.

The GSS has not been validated as a measure of academic freedom

The questions analysed from the GSS were first asked in 1954 by Samuel Stouffer in his landmark study of American attitudes about civil liberties and political tolerance for atheists, communists, and socialists. Stouffer’s study was conducted during the Second Red Scare and on the heels of the Army-McCarthy hearings, a time when many scholars had their intellectual integrity questioned, were denied or stripped of tenure, and even lost their positions because they were suspected of holding communist sympathies. The conclusions were presented as an analysis of political tolerance of nonconformists and no explicit conclusions about attitudes toward academic freedom were drawn.

When the GSS began in 1972, the questions about all three controversial figures from Stouffer’s 1954 study were included. Although the questions about a socialist have not been asked since 1974, the questions about an atheist and a communist have been asked in every administration of the GSS. In later years, different controversial figures were added to the battery of questions. The consistent inclusion of the Stouffer questions in the GSS has produced a voluminous literature on political tolerance and how it has changed in the United States over the past five decades. Although, just like Stouffer, almost all of this scholarship draws conclusions about political tolerance, not academic freedom.

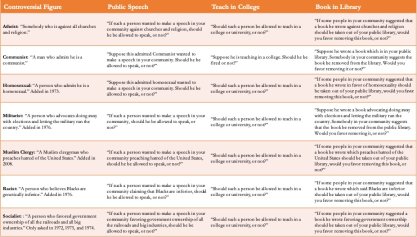

It is not unreasonable to think that such questions may also measure attitudes about academic freedom, particularly the one focused on teaching in a college or university. However, such a conclusion requires, at the very least, a demonstration of strong correlations between responses on the GSS questions (all items listed in the table below) and other questions measuring attitudes towards academic freedom. For instance, a question such as, “There’s no room in the university for professors who defend the actions of Islamic militants,” taps into attitudes toward academic freedom because it clearly indicates a controversial view that the professor has expressed, either in the classroom or outside of it. In contrast, a question that describes a controversial figure as “admitted homosexual” and then asks if “Such a person should be allowed to teach in a college or university?” is focused on the identity of the controversial figure. In the absence of such correlational evidence, it remains an open empirical question as to whether the questions analyzed from the GSS also provide a valid measure of attitudes about academic freedom.

Distorted conclusions about political tolerance

All of the conclusions in the AAUP’s data snapshot rely on combining “[t]he average percentage of respondents who support free expression in the three venues across the various views over the last six decades.” This is a curious decision for a few reasons:

First, although there are some scholars who suggest that all of the questions from the GSS should be combined into a single measurement scale of general tolerance, this is not typically done. Second, the analyses excluded two of the hypothetical controversial targets that the GSS asks about: a homosexual and a Muslim clergy member preaching hatred of the United States. These decisions are problematic because they distort overall levels of tolerance and somewhat mask the level of agreement between liberals and conservatives on who should be allowed to speak, teach, and keep a book in the library.

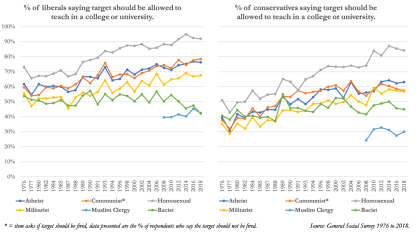

The main reason the GSS questions are not often combined into a single measure of political tolerance is because tolerance of the target depends on who that target is. As can be seen in the figure below, there is a good deal of variance in tolerance for a professor who holds a controversial idea among liberals and conservatives. This pattern largely holds for making a public speech and for keeping a book by a controversial figure in the public library, although the differences between the different controversial figures are not as stark in those domains. Thus, the AAUP is right to observe that there is a consistent difference in tolerating a potentially, controversial professor on the one hand, and a controversial speaker or author on the other hand.

Furthermore, as noted in the data snapshot, liberals in 2018 were more tolerant of allowing most of the controversial figures to teach in a college or university. At the same time, both liberals and conservatives were overwhelmingly tolerant of a homosexual professor, and a majority of conservatives were tolerant of an atheist professor, a militarist professor, and even a communist professor. At the other end of the spectrum, majorities among both liberals and conservatives were reticent to extend tolerance to a racist professor or one who is a Muslim clergy member preaching hatred of the United States. Yet, averaging responses across controversial figures and the different venues of expression distorts the conclusions reached about tolerance. Specifically, they mask similarities between liberals and conservatives and ultimately underestimate the levels of tolerance that exist for most of the controversial figures the GSS asks about among the American public.

The least-liked group method: A superior, content-controlled measure of political tolerance

The consistent inclusion of the Stouffer questions in the GSS has produced a voluminous literature on political tolerance and how it has changed in the United States over the past five decades. One of the conclusions more often cited is that tolerance for nonconformists tends to increase with each subsequent generation primarily because of increased education, although there are reasons to be skeptical of this conclusion. But, a number of scholars contend that political tolerance is better measured with the least-liked groups method.

The least-liked group method was developed by Sullivan, Pierson, and Marcus. It is considered a content-controlled method because, unlike the Stouffer questions, people are asked to identify controversial groups or figures they dislike before being asked if they will tolerate them. This method has been referred to as “the standard technology” for measuring political tolerance by James L. Gibson.

When the least-liked group method is employed, scholars typically report that:

- Large majorities are politically intolerant of their least-liked political groups;

- The least-liked group changes in response to political events; and

- The selection of targets for political intolerance is primarily driven by ideological identification, with people on the right more intolerant of groups on the left, and people on the left more intolerant of groups on the right.

As a result of these consistent findings, scholars employing the least-liked group method maintain that it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions about tolerance of a controversial figure if one does not know what a given person actually thinks of that figure. It is therefore not that surprising that the GSS data shows liberals are more tolerant of atheists, communists, and homosexuals compared to conservatives. Furthermore, it is likely that if the GSS assessed attitudes toward different controversial figures, one would see a different and more nuanced pattern of results.

Conclusions

In sum, although the AAUP’s data snapshot brings attention to the important issue of academic freedom and attempts to ascertain what the American public may think about the issue, it is not clear that the analysis tells us much about people’s attitudes toward academic freedom. This is because the questions used in the analyses from the GSS have long been considered measures of political tolerance, a related but presumably distinct construct. Firm conclusions about what the American public thinks about academic freedom require data that more narrowly assesses such attitudes. Furthermore, the decision to collapse controversial figures and venues into a single measure of tolerance distorts conclusions about the overall levels of tolerance for most of the controversial figures the GSS asks about. It also masks some prominent similarities in tolerance among liberals and conservatives with regard to who can speak in one’s local community, who can teach in a college or university, and who can have a book in the public library. This more detailed analysis reveals that a good number of both liberals and conservatives are tolerant of controversial views in a university setting, however this tolerance is less likely to be extended to a professor who is racist or a professor who is a Muslim clergy member known for preaching hatred of the United States.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

BREAKING: New Title IX regulations undermine campus free speech and due process rights

Stanford president and provost cheer free expression in open letter to incoming class