Table of Contents

Rising censorship, falling trust: How lack of transparency erodes trust in higher ed and beyond

In early February, in a flagrant breach of community trust, the president of George Washington University expressed his intent to uncover individuals responsible for engaging in protected expression on campus. The expression in question? Posters featuring artwork by Chinese dissident artist Badiucao, which, despite their glossy illustrative style, explore a dark theme: China’s human rights abuses.

Fortunately, President Mark S. Wrighton, who initially claimed to be “personally offended” by the posters, later announced in a public letter that there would be no investigation, and even proclaimed the value of free speech. “I support freedom of speech — even when it offends people,” said Wrighton, “and creative art is a valued way to communicate on important societal issues.”

FIRE agrees, and applauds this sentiment. But the question remains: Why the about-face?

Perhaps Wrighton, initially under public pressure from the GW Chinese Students and Scholars Association and GW Chinese Cultural Association to investigate the posters, was inspired to defend free speech when faced with public pressure of a different sort, from civil-liberties-minded individuals and institutions.

Luckily, organizations like FIRE exist to hold institutions like GW accountable to their stated promises, artists like Badiucao are not easily cowed into silence by pressure, and some keyboard warriors use their voices to protect expression, not to stifle it. But what if they didn’t? Can we trust the leaders of our once-venerated institutions to uphold and consistently apply the principles that once earned them widespread respect? Or are policies and their selective enforcement just determined by a giant game of public-pressure tug-of-war?

Beyond higher ed

“Trust must be earned to be given,” goes the old cliche. Or is it, “Trust must be given to be earned”?

By choosing PR over principles, institutions like GW impressively manage to violate both interpretations of this phrase, at once failing to act in ways that merit trust and failing to entrust their communities to contend with complicated topics with maturity.

Indeed, trust in most major U.S. institutions has generally trended downward over the course of the past 20 years.

According to a Gallup poll, between 2020 and 2021, Americans’ trust declined in almost all institutions about which they were surveyed. The 2021 findings reveal that fewer than half of those polled have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the presidency, the medical system, and public schools. Fewer than one-fourth have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in Congress, newspapers, and television news.

Pair this with a Pew Research Center poll on public trust in government from 1958 to 2021 — revealing near-record low levels of trust in 2021 — and the phenomenon of our collective “trust issues” appears in stark relief.

A censorial culture

Is it a coincidence that this decline in trust has occurred in an age in which many institutions and individuals openly advocate for — and engage in — censorship?

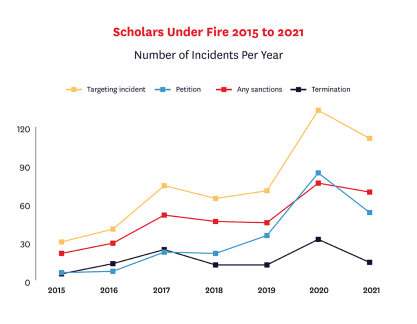

The past few years have been some of FIRE’s busiest on record due to disturbing trends toward censorship in higher education. FIRE’s recently released Scholars Under Fire report reveals that since 2015, the number of targeting incidents — in which people call for the sanctioning of their ideological adversaries — at colleges and universities has risen. More worrying still is the fact that nearly half (46%) of targeting behavior is driven by undergraduate students. If this is a sign of what’s to come it might read, “Warning: illiberal times ahead.”

As the global community weathers a pandemic and escalating international tension, censorship and cancelation attempts, once thought of as uniquely #HigherEdProblems, have become undeniably prevalent in the world beyond it. While FIRE does not take an institutional position on censorship by private entities that don’t promise free expression, such as social media companies, censorial policies in this sphere undoubtedly shape our culture.

At the helm of American censorship, heads of social media giants like Facebook and Twitter act as self-appointed captains of the digital public square, steering users toward murky informational waters by instituting selectively enforced content moderation policies relient on subjective definitions of “misinformation,” perhaps taking a page from the U.S. government’s own concerningly vague definitions of “mis-,” “dis-,” and — wait for it — “malinformation.”

Understanding that even hateful opinions and misinformed claims reflect real perspectives, we might publicly unpack, disprove and refute them instead of sending them away to metastasize somewhere else.

Such easily abused policies give fuel to armchair activists’ efforts to deplatform people who they believe have transgressed the norms of acceptable speech. Even when unsuccessful, campaigns to convince big companies like Spotify to remove Joe Rogan’s podcast or Netflix to remove Dave Chappelle’s comedy special reveal a disturbing new reality in which many view censorship as a valid and necessary means of leading the public to the “correct” consensus on important issues, and believe that if they demand it loudly enough, leaders of our institutions will oblige. While the public awaits new developments in stories of attempted takedowns of globally recognized celebrities, how many lower-profile cancellations occur quietly, never to garner widespread attention?

In this environment, in which restrictions are many, tensions are high, and rules are arbitrarily applied, is it any wonder that trust is low?

The censor’s dilemma

Critics of unfettered free expression often cite the problem of information siloing, the idea that with unlimited options available, people gravitate toward content that suits their preconceptions and choose to interact only with those who share their views — which become more and more extreme as they wander down the rabbit hole. Don’t those in positions of power, the argument goes, have a responsibility — a duty — to mitigate this undesirable effect?

Maybe so, but can we trust the very people who benefit — financially and reputationally — from the proliferation or suppression of particular information with the responsibility of curating it?

While it’s true that people gravitate toward information that confirms their biases, it is unclear to what degree this behavior occurs naturally and to what degree it is manufactured by systems that incentivize it. Without employment infrastructures that reward conformity, or social media algorithms specifically designed to exploit tribalist tendencies, perhaps the dominant discourse would be more nuanced and friendly, in which case, the argument for cracking down on free expression would naturally hold less sway.

Not to mention the fact that peoples’ mere awareness of censorship and its inconsistent application surely drives some with “unacceptable” views away from some institutions and toward others, filtering them into more siloed spaces that they otherwise would not have sought out. In other words, even when censorship is well-intentioned, it may produce more of what it seeks to destroy.

Breaking barriers, building trust

Co-founders of publishing platform Substack, Hamish McKenzie, Chris Best, and Jairaj Sethi believe that their platform’s newsletter-based subscription model — free of manipulative algorithms — holds the key to higher-quality content. In a Substack article, “Society has a trust problem. More censorship will only make it worse,” they claim that institutions which wish to mitigate mistrust should interfere less with content-curation and allow more expression. “Knowing that they are on a platform that defends freedom of expression can give writers and readers greater confidence that their information sources are not being manipulated in some shadowy way,” they write.

Indeed, honesty is central to trust. In interpersonal relationships, trust is built over time as patterns of open communication and reliable behavior are established. Likewise, trust develops between institutions and individuals over time through transparency and consistency.

Can we trust the very people who benefit — financially and reputationally — from the proliferation or suppression of particular information with the responsibility of curating it?

Leaders of institutions like George Washington University might talk a big game when their commitment to free speech is publicly questioned, but “integrity,” as the famous saying goes, “is doing the right thing even when no one is watching.” The more often an institution’s private actions mismatch its public promises, the flatter those promises will fall, and the more public skepticism it will warrant.

In the U.S., even if we have little else in common, we share a political system and countless public and private institutions. Building and maintaining enough trust in these institutions to enable them to perform their purpose and exercise their expertise, for our mutual benefit, is essential to society’s basic functioning.

Fortunately for our not-so-revered institutions, trust, once lost, need not be lost forever. But it can only be rebuilt when information-curation is left largely to the people, who are at least as capable of deciding for themselves what to read and how to think as are our industry and government leaders, who, notwithstanding “lizard-person” memes, are human too, after all. Understanding that even hateful opinions and misinformed claims reflect real perspectives, we might publicly unpack, disprove and refute them instead of sending them away to metastasize somewhere else.

Finally, knowing that people lose trust in those who are deceptive, perhaps we have reason to be optimistic that fewer restrictions on expression will lead, over time, not to a hellscape of vitriol and disinformation, but to an imperfect yet vibrant society in which — more often than not — accurate and constructive commentary wins the day.

Of course, achieving this vision depends on leaders’ willingness to practice transparency and phase out systems that rely on manipulative designs. As long as this seems far-fetched, those of us who spend more time navigating than designing our systems are right to view their governing authorities with heavy scrutiny, to remain vigilant to abuses of power, and to exert social pressure to produce positive change.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

A third of Stanford students say using violence to silence speech can be acceptable

FIRE survey shows Judge Duncan shoutdown had ‘chilling effect’ on Stanford students

USC canceling valedictorian’s commencement speech looks like calculated censorship