Table of Contents

Video of AHA Free Speech Debate

The History News Network has posted video from the debate over speech codes that took place this past weekend at the American Historical Association (AHA) conference—a debate that ended with the rejection of a resolution providing that “the American Historical Association opposes the use of speech codes to restrict academic freedom.”

The AHA debate featured opponents of the resolution dragging out some of the same tired old chestnuts they have been using for years to defend speech codes on campus. In particular, Pamela Smith, who opposed the resolution, said that:

This resolution negates the complexity of the problem of balancing the constitutional right to free speech with the responsibilities that must go along with this right. This is a complexity and a problem particularly for administrators.

This is a fundamental mischaracterization of the First Amendment. The First Amendment is not something that can simply be taken under advisement and “balanced” against other concerns. When it applies (when the speech in question is constitutionally protected, and the would-be censor is a public university), it trumps other, non-constitutional rights that a university might wish to guarantee its students, such as the right to a civil and tolerant environment. Certainly, people should exercise their right to free speech responsibly, and universities can—and even should—encourage them to do so. But the responsibility to show restraint in one’s speech is a purely moral responsibility incumbent upon speakers, and not something that can lawfully be codified in policies at a state university (or at any college or university that promises free speech).

Smith also expressed concern that condemning “speech codes” would mean condemning “state-mandated sexual harassment policies.” Again, this concern stems from a misunderstanding of the First Amendment. The type of harassment that universities are required to prohibit under federal anti-discrimination law—harassment “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively bars the victim’s access to an educational opportunity or benefit”—not only isn’t protected by the First Amendment, it is an unlawful pattern of behavior that is not even considered speech at all (harassment may be effectuated by the use of words, just as fraud may, but in both cases what is prohibited is the conduct itself). Just as academic freedom does not include the right to make defamatory statements or to threaten students’ lives, academic freedom does not include the right to engage in unlawful harassment of the variety prohibited by state-mandated sexual harassment policies. Thus, Ms. Smith’s concern is inapposite. However, should the resolution’s sponsors decide to reintroduce the resolution at a future meeting, they could easily address this concern by simply defining speech codes in the resolution explicitly to mean policies restricting constitutionally protected speech. Again, the use of the academic freedom language has essentially the same effect, since academic freedom does not include the right to engage in unprotected speech, but perhaps that minor clarification would help a future version of the resolution pass.

It is a sad commentary on the state of free speech in academia that the AHA could not agree to something as basic as condemning policies that restrict student and faculty speech that would otherwise be protected by academic freedom. Resolution sponsor Ralph Luker commented to the crowd that he would be “a little hesitant to move the adoption of the Bill of Rights in a body like this.” His comment drew laughs from the audience, but there was no doubt more than a grain of truth in what he said. Let’s hope that the AHA reconsiders and passes this resolution at its next meeting.

Recent Articles

FIRE’s award-winning Newsdesk covers the free speech news you need to stay informed.

TikTok legislation sets grave precedent for free speech

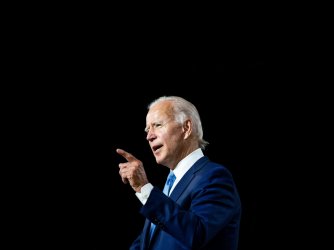

President Biden today signed legislation that kickstarts a process to ban TikTok and empowers the president to block other communications platforms used by millions of Americans.

FIRE joins animal advocates, free speech groups urging Ninth Circuit to affirm ruling that allows undercover audio recording

Secret recordings are essential to news gathering, exposés, say advocates in Project Veritas case.

Louisiana Tech earns top rating for free speech

Louisiana Tech University is the latest school to receive a “green light” rating from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression

German police forbid ‘speaking Irish’ at Berlin protest — Free Speech Dispatch April 2024

Free speech trouble spreads across Europe, app censorship in China, and how Iran suppresses critics abroad.