Table of Contents

America’s most controversial publisher

Research & Learn

The life and times of Lyle Stuart, publisher of The Anarchist Cookbook and The Turner Diaries.

By award-winning writer Amy Sohn.

In April 1995, a Gulf War veteran named Timothy McVeigh bombed a federal office building in Oklahoma City, killing 169 people in the largest domestic terror attack in American history. Inside a white envelope in his car were pages from a 1978 novel called The Turner Diaries, a book that has allegedly inspired 200 murders since its first publication. Written by the neo-Nazi William Luther Pierce, it depicts a race war between an underground white group and a Jewish-dominated government, blacks, and other minority groups.

Before the bombing, the book had been mostly available through hate groups, but afterward, a New York free speech advocate and publisher, Lyle Stuart, decided to republish it. He appended his own foreword that criticized the book, writing that the public had “the right to know what the enemy is thinking.” Stuart himself was Jewish by birth, but recognized the publicity value of reissuing a book said to have inspired a shocking act of domestic terror.

He told reporters he was publishing The Turner Diaries to “alert the average American to what these people advocate.” The Southern Poverty Law Center tried unsuccessfully to get bookstore chains not to sell it, calling it “an invitation to kill blacks and Jews.”

“I’m a First Amendment fanatic,” Stuart said. “I feel the American people should have a right to read anything.”

‘To think as they wish’

Stuart was one of the most important free speech publishers of the 20th century, and his legacy is especially relevant in the wake of the Trump administration’s assaults on the constitutional rights of publishers, broadcasters, and comedians. He believed publishing could, and should, explore controversial ideas, and did not agree with everything he printed. In a 1951 essay, he wrote, “If democracy is to survive, there must always be dissent . . . There must always be the struggle for the complete freedom for all men to think as they wish, to speak as they wish, to write as they wish.”

Born Lionel Simon in Brooklyn to a secretary and a salesman on Aug. 11, 1922, he attended James Madison High School with future Mad magazine publisher William Gaines. He dropped out of school to join the Merchant Marines and served in the Air Force during World War II. While in the military, he changed his name to Lyle Stuart because of the antisemitism he encountered. He was five-nine and had lifelong struggles with his weight.

After the war, Stuart bounced from one writing gig to another. He worked as a journalist for the International News Service in Ohio, covering censorship in film and radio and writing an investigative piece on a bill that benefited the beer lobby. When INS apologized to the beer barons — who had taken out ads supporting the bill — he resigned in protest and moved to New York City. He wrote radio scripts for the State Department and took a job writing for Variety. His self-published novel about newspaper reporting, God Wears a Bow Tie, sold 275,000 copies.

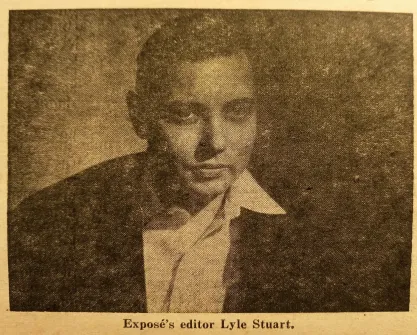

In 1951 Stuart got the idea to launch a publication “where a story could appear without its editor and/or publisher being concerned about whether it might irritate an advertiser, or stir up a boycott by a pressure group, or anger a stockholder.” He named it Exposé. In America in the early 1950s, as he wrote, “there was an undercurrent of tension that was turning into fear and hysteria, that was acting to silence people, to shrink free expression.”

Stuart founded Exposé with his first wife, the former Mary Louise Strawn, and childhood friend Joe Whalen, subletting an apartment in midtown Manhattan from a man he called a “white Russian sympathizer.” The office had a single desk and a couch, cardboard boxes for file cabinets, and one typewriter.

A publication such as yours

To find subscribers, Stuart compiled a list of 100 contacts including Congressmen, newspaper reporters, and executives. Seventy-one subscribed. After Alan Reitman, the ACLU assistant director, read the first issue, he wrote Stuart, “It is vital that we have a publication such as yours on the American scene.”

Though the first issue only sold around 1,000 copies, Stuart hit the jackpot with the second, selling nearly 100,000.

By publishing information which ordinarily would not be available elsewhere, I believe Exposé can render the American people a much-needed service. Expose’s growth will depend on a chain reaction: that readers will tell readers; that subscribers will encourage new subscribers.

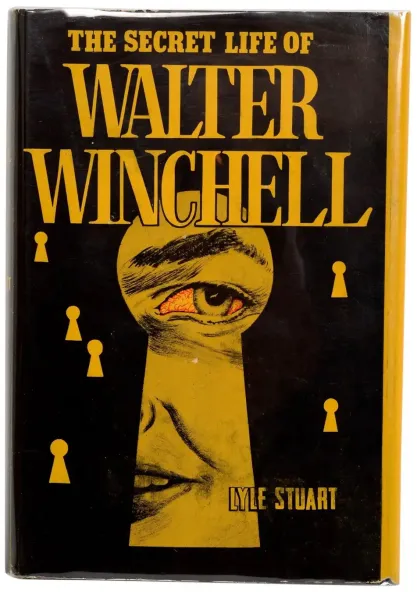

Earlier in his career, he had been a contributor for the notorious gossip columnist Walter Winchell, who had exposed the secret lives of the rich and famous since the 1920s. Winchell had allied with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Sen. Joseph McCarthy in their attacks on Hollywood, and was known for being racist and antisemitic despite being Jewish himself. By the early 1950s, Stuart, a civil rights supporter, had come to loathe Winchell.

So when Stuart read a column in which Winchell smeared the black chanteuse Josephine Baker, the bald racism enraged him and he set out to ruin Winchell. He stayed up all night to write a hit job — “The Truth About Winchell” — that called the columnist vain and “psychopathic” and said his work was “one of the greatest hoaxes ever put over on newspaper readers.”

That issue of Exposé flew off the newsstands (Stuart claimed that eventually 91,000 copies were sold). He turned the article into a book, which was republished by the Ulysses publisher Sam Roth (of Roth v. United States notoriety).

Winchell attacked Stuart and Roth in print, radio, and television, saying Stuart had been convicted for extortion (he had received a suspended sentence in 1942) and calling them both communists. In retaliation, Stuart launched three separate libel suits against Winchell and collected on all of them. With $8,000 from one suit, he launched his first publishing company: Lyle Stuart, Incorporated.

Testing the limits of the First Amendment

There is no present-day comparison for Exposé (which Stuart renamed The Independent in 1956). It was a mix of investigative reporting — much of it on American foreign policy — and issues of interest to consumers. Think The Nation meets Mother Jones meets Consumer Reports. Similar magazines, like Ralph Ginzburg’s Fact, would follow.

In its nearly two decades of existence, it ran investigative stories about Big Tobacco, Hearst newspapers, the Du Pont family, the American Medical Association, and the Catholic Church, taking down powerful institutions and railing against their hypocrisy, duplicity, and secrecy. Early stories covered life insurance, cost-conscious shopping, Jim Crow laws, sex in prison, and General Electric’s dealings in the metal black market. Stuart never revealed a source or published a retraction. Within two years, circulation was high enough that he stopped selling it at newsstands.

Stuart’s own willingness to turn to the courts for revenge was part and parcel of a grudge-keeping personality.

A major but overlooked figure in the sexual revolution, Stuart hired the very first sex columnist in an American newspaper, Albert Ellis, founder of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy and one of the most significant psychologists of the 20th century. Stuart’s young managing editor, Paul Krassner, sent Ellis a letter to see if he had articles other magazines had refused to publish. He said yes. (Krassner would later name the Yippies, for “Youth International Party,” and become a major player in the group’s 1960s and 1970s free speech and antiwar protests.)

The column was a hit — though many readers canceled subscriptions — and covered topics like masturbation, clitoral orgasms, and “sex fascism,” or narrow-minded thinking. Stuart became Ellis’s book publisher and titles like Sex and the Single Man (1963) and The Art and Science of Love (1960) were among his bestsellers.

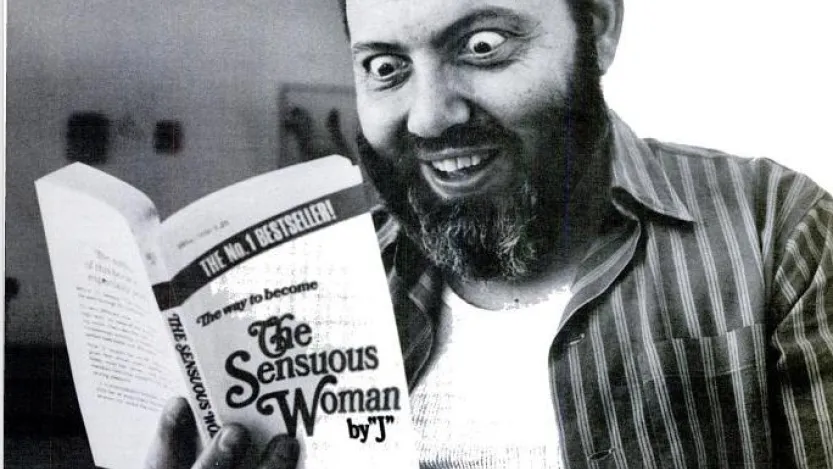

All Lyle Stuart books had broad appeal but also unearthed aspects of life not commonly discussed — like experimental medicine, American policies in Latin America, and marital intimacy. Stuart used direct mail to sell them in an era when many bookstores would not carry difficult material, which also allowed him to maximize profits. A 1961 book defending Castro’s activities in Cuba caused the State Department to deny Stuart a visa to visit Cuba. Naked Came the Stranger (1969) was a sexual satire claiming to have been published by a housewife but actually written by a bunch of journalists to prove how easy it was to sell shlock. The Anarchist Cookbook (1971) taught the author of this article how to get high off banana peels and other readers how to make bombs.

Stuart was extremely successful. The New York Times reported in 1969 that he made around $4 million a year — $35 million in today’s dollars. He loved taking down powerful figures, with books on subjects like J. Edgar Hoover, Howard Hughes, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and Anna Nicole Smith. But he never carried libel insurance because he felt it was too expensive.

Stuart’s final years

In 1990, Stuart sold his publishing company and started a new one, Barricade Books. By 1995, when he republished The Turner Diaries, he was in his early 70s. “I’m a nut,” Stuart said to The Washington Post in 1996. “I’ve always tested the limits of the First Amendment. I’m a great believer in letting anybody publish the most outrageous, unpopular things there are.”

But then his luck started running out. In 1995, he published an unauthorized biography of casino mogul Steve Wynn and called him a front man for the Genovese family. Wynn sued and won a $3 million defamation award. The judgment was later reversed, but Barricade Books went into bankruptcy. Stuart died in Englewood, New Jersey, in 2006, at age 83.

Stuart’s own willingness to turn to the courts for revenge was part and parcel of a grudge-keeping personality. “There’s nothing Lyle loves better than giving an enemy a stomach ache,” recalled his former classmate Bill Gaines.

In the inaugural issue of Exposé Stuart laid out what would become the mission of all his ventures: “By publishing information which ordinarily would not be available elsewhere, I believe Exposé can render the American people a much-needed service. Exposé's growth will depend on a chain reaction: that readers will tell readers; that subscribers will encourage new subscribers.”

By fundamentally believing that many Americans wanted to read truthful and good writing about important and under-reported stories, he created a niche that at that point did not exist on a large scale. This laid the foundation that enabled other countercultural publications (Fact, The Realist, The Village Voice, the alternative press in the 1960s-1970s, Spy) to find readers, too, and brought investigative reporting into the modern era.

Amy Sohn is the author of 13 books including the novels "Prospect Park West" and "Motherland." Her most recent, "The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age," tells the stories of eight women prosecuted under the Comstock law. It won a First Amendment award in book publishing from the Hugh M. Hefner Foundation and was named a Smithsonian Top Ten History Book.

Read More

The Deported: Emma Goldman and activist persecution under the 1917 Espionage Act

History

‘All who think outside the conventional ruts’: A history of the Free Speech League

History