Table of Contents

So to Speak Podcast Transcript: Remembering 'free-thinking' writer Nat Hentoff

Note: This is an unedited rush transcript. Please check any quotations against the audio recording.

Nat Hentoff: My name is Nat Hentoff. I am 88½ years old, and I am a reporter. Sometimes I write books. And my reporting has essentially been, for well over 60 years, in large part, about how to keep this country what it’s supposed to be, a self-governing public.

MLK: Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech.

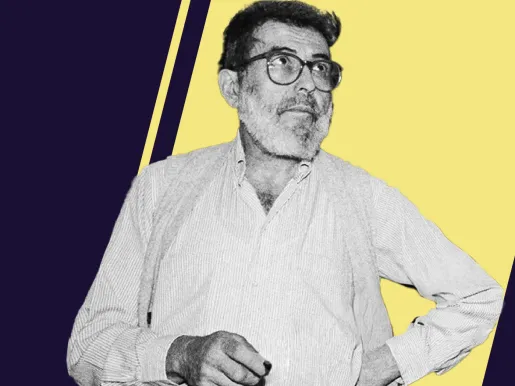

Nico Perrino: You’re listening to So To Speak: The Free Speech Podcast, brought to you by FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. All right, folks, welcome back to So To Speak: The Free Speech Podcast, where every other week, we take an uncensored look at the world of free expression through the law, philosophy, and stories that define your right to free speech. I am your host, Nico Perrino. On January 7th, 2017, the Associated Press announced that free-thinking author and columnist Nat Hentoff is dead at 91. I came to know Nat early in my FIRE career. Occasionally, Nat would call Greg Lukianoff, FIRE’s president, and ask for some information about one of our cases.

Nat famously didn’t do email, so he would ask Greg to fax him the information. I was Greg’s assistant at the time, so the task fell to me. The problem was, I was just out of college and didn’t know how to use a fax machine, but I had to learn. It was the Nat Hentoff asking. For well over 60 years, Nat was one of America’s foremost public intellectuals and a familiar byline to free speech advocates and jazz aficionados the world over. He was arguably the world’s preeminent jazz critic and a pioneering crafter of so-called liner notes for jazz albums.

In 2004, Nat was the first non-musician to receive the title of jazz master by the National Endowment for the Arts. Nat moved to New York City from Boston in 1953. And in the towering writing career that followed, he wrote dozens of non-fiction books, novels, children’s books, and memoirs. He interviewed some of the 20th century’s most prominent cultural figures for his newspaper columns, including Malcom X, Che Guevara, and Bob Dylan.

In fact, he wrote two of the most famous profiles of Bob Dylan, one for the New Yorker and another for Playboy. And he provided liner notes for Dylan’s second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. In 1980, Nat published his first book on free speech, which covered the history of free speech in America. And in 1992, he published Free Speech for Me — But Not for Thee: How the American Left and Right Relentlessly Censor Each Other, which remains a classic defense of free speech, even to this day, with the book’s title also becoming an online meme.

For Nat, free speech was a defining characteristic of the individual. It imbued all aspects of life. Indeed, seemingly disparate passions for the constitution and jazz weren’t so different according to jazz percussionist and composer Max Roach, who once remarked to Nat, “You know, Nat, you write a lot about. . .”

Nat Hentoff: “You write a lot about the Constitution.” What do you think we do? What we do in jazz, we are individual voices, right? Have to be. And we come together, and that voice is different, sometimes larger, than some of the parts. Isn’t that what you’re talking about?

Nico Perrino: For my part, Nat Hentoff was the quintessential free speech civil libertarian, always principled and always fiery. And this marked his 100th birthday. So, to commemorate the occasion and discuss his life and legacy, we are joined by his son, Nick, and filmmaker David Lewis, who directed the Pleasures of Being Out of Step, a fantastic documentary profiling Nat’s life as a jazz critic and a civil libertarian. Nick Hentoff, Davis Lewis, thank you for joining us on So To Speak.

David Lewis: Thank you for having us.

Nick Hentoff: Thank you, Nico.

Nico Perrino: David, let’s start with you. Why make a movie about Nat Hentoff?

David Lewis: It was really a personal choice, I have to say. I grew up reading the Village Voice and always admired his work and his willingness to be outspoken and speak truth to power, at least as I saw it then. And I didn’t know that much about jazz music, and I wanted to learn about it. So, that was an added benefit.

Nico Perrino: What do you think Nat was most known for? At that time, when you were making the film, the late 2000s, early 2010s, what were people associating with the name Nat Hentoff?

David Lewis: Well, by that time, he had been writing for the Village Voice for 50 years, or so, I guess. So, I would have to say that is how he was best known. Although if you were a jazz fan and you grew up reading his liner notes, you knew him very deeply.

Nico Perrino: And what are liner notes, for our listeners who are maybe younger, and haven’t heard that phrase before?

David Lewis: Well, the liner notes, you don’t see them that much anymore, are for the big 12” LPs when they were invented on vinyl. I guess vinyl is coming back now. I don’t know if liner notes are coming back, but there was a lot of space on the back of those album covers, and so they hired writers to write about the album, about the music that was being made. Nat often focused on that exclusively.

I think in rock, a lot of bands put their own liner notes on the albums, but back in the day, they used to hire writers to write them, and Nat would interview the musicians and ask them about the music and what they were trying to accomplish with the music, and use his own ear, and write it up that way. Some of them are quite memorable, and a lot of people learned about jazz by reading those liner notes.

Nico Perrino: And Nick, what was it like to be Nat Hentoff’s son?

Nick Hentoff: Well, from my earliest memories, it seemed perfectly normal that everyone was talking about your father. Didn’t everybody have a father who appeared on TV frequently? Didn’t everybody have a father who was on the radio, or who wrote and was published and was talked about? And the most frequent question I got growing up, after I told the person what my name was, the question would be, “Are you related to Nat Hentoff?”

And it’s something that’s been a feature of my life, from the very beginning, all the way up to the present. I remember that the first time I appeared in a newspaper was when I did the unusual thing for a 12-year-old, and I bought at auction an autographed document signed by both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. And the gallery owner, a guy named Charles Hamilton, who was kind of like an impresario, a P.T. Barnum of the autograph industry, he released that to the AP wire.

Back then, the AP wire was fed to all the little newspapers all across the country. Hundreds and hundreds of newspapers, unlike today, where you only have one or two newspapers mainly surviving in a state. And so, the article started out, was, “Nicholas Hentoff, 14 years old, 13 years old, son of journalist Nat Hentoff, bought a $2,200.00 autograph signed by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.”

And that was when I was 13, 14, and it continued up until I went to my reunion recently at Cornell University, and a friend of mine, Tom Allen, and I ran into the editor of that Cornell Daily Sun, which we both work for. And he said, “Francis, do you remember Nick?” And she said, “Oh yeah, Nat Hentoff’s kid.”

Nico Perrino: Nat famously was described by the editor of the Washington Post as someone who would walk into a garden party and put on a skunk suit. He had some controversial opinions. He wasn’t afraid to speak his mind, as the Associated Press put in its lede to his obituary. Was any of that kind of baked into the conversations you were having with your peers who recognized his name?

Nick Hentoff: Yeah. It was never really negative. It was always people approached it with a great deal of respect. They were very impressed when they would learn that my father was Nat Hentoff. You know, I got to use a stock line after a while, where people would ask me, “Are you related to Nat Hentoff?” And my response was, “Only by paternity.” And it changed a little bit in the 1980s, late ‘80s, the ‘90s, when he started to take on a little bit more controversial subjects that weren’t exactly part of the liberal orthodoxy that developed during the 1960s.

Nico Perrino: He was prolife, famously, right?

Nick Hentoff: He was. He was very prolife, and he was a believer, although he was not a Catholic, and although he did do a book-like profile for the New Yorker that actually became a book on Cardinal O’Connor of the New York diocese. He believed in the Seamless Garment, and he believed in the sanctity of life from birth to death, and he was against the death penalty.

David Lewis: Actually, he said from conception to death, I think.

Nick Hentoff: From conception to death, and it was very important to him. It became an issue when people started to talk about reproductive rights.

David Lewis: I’m just thinking here. He wasn’t the skunk at the garden party in his jazz career. He rarely wrote about musicians that he didn’t like, and rarely criticized musicians, so it’s interesting to think about it that way. When he went to the Voice, and he started writing about other things, that’s when he really started to speak freely.

Nick Hentoff: David, didn’t he lose a friendship with, wasn’t it, Miles Davis, for his review of Bitches Brew? I don’t know if you guys recall that.

David Lewis: It’s possible. It’s possible. Amiri Baraka was a famous activist and poet, got his start as a writer. Nat hired him to write about jazz. He tells the story in the film about going up to Miles and asking Miles for an interview. And Miles says, “No.” Baraka says to him, “I bet if I was Nat Hentoff, you would do it.”

Nick Hentoff: I wanted to put it in context. The skunk in the garden party comment had to do with his willingness to be unpopular if he felt that it was right to be unpopular. And he learned that at a very early age. He went to Boston Latin School, which was the leading public secondary school in Boston at the time in Massachusetts. And during that time, he worked for an activist and journalist named Francis Sweeney. And Francis Sweeney was an Irish immigrant Catholic who spent most of her time fighting against other Catholics who were antisemitic. She fought against church leaders like Father Coughlin and cardinals who would support his virulently antisemitic and right-wing views.

Coughlin was an active supporter of Hitler during the 1930s and of Mussolini. And she was the prototypical skunk at the garden party. She would walk into Catholic gatherings and tell them that what they were talking about was wrong, and he worked for her as a very young student in middle school and going forward. And he had an affinity for labor leaders who would go in and disrupt the status quo at workplaces. He famously organized the candy shop that he worked at when he was a young boy. And that’s the kind of context that you want to understand in the garden party comment.

It wasn’t going in, like we have politicians today that are skunks at garden parties all the time, and they stink things up just to be controversial, or just to offend people. That’s not what we’re talking about here. What we’re talking about here is going in and being willing to speak truth to power, even when that’s going to be unpopular and put you at odds with people in the room that you’re speaking with.

Nico Perrino: David, Nick brings up Francis Sweeney, who is someone that you also discuss in your film. I’m wondering if you can tell us about how those early years of Nat’s life helped shape him. He was born in 1925, as I had mentioned at the top. This would’ve been his 100th birthday. He grew up in Roxbury, which is a neighborhood in Boston. He spent his first 28 years in the city. And he said he had managed to grow up unmaimed in the most antisemitic city in the nation. How did antisemitism, his parents’ immigrant background, and just the environment in Boston in those early years help shape who he would become in his later years?

David Lewis: Well, he often told me how his father loved to listen to Father Coughlin’s radio show to hear all the antisemitism being spewed and would pull over the car to the side of the road when they were driving and Father Coughlin came on the radio. But I think that he did experience antisemitism. There’s no doubt about that. He tells the story of being accosted by a gang of young toughs, I guess we would call them. They asked him, “Are you Jewish? Are you Jewish?” And he thought, and he responded, “No. I’m Greek.” And he was always ashamed of that. In later years, he still talked about it.

As far as Francis Sweeney goes, I can tell you that when I showed him the film for the first time, and there were photos of Francis Sweeney in it, he said to me afterwards, he said, “I’ve written two or three volumes of memoirs, but nothing has brought it back home to me than this film, and being able to see Francis Sweeney in real life.” All those years later, just seeing her photo triggered that in him. So, that’s how important that experience was to him.

Nico Perrino: Nick, your dad was culturally Jewish, right? He wasn’t religious. He tells the story in one of his memoirs about eating a salami sandwich on one of the holy days, as his neighbors were walking to synagogue. And he sort of reveled in the experience of being a heretic. And he was even excommunicated by some rabbis at some synagogue, I guess, in Massachusetts, and he didn’t have the opportunity to defend himself, I believe, is how he described it. How did his Jewish background, although he always associated himself with Judaism, I believe he writes in one of his memoirs that so long as Jews are persecuted, he will be associated with Judaism. How did that shape his early life in the years to come?

Nick Hentoff: I think the excommunication occurred during the first war in Lebanon.

Nico Perrino: Yes.

Nick Hentoff: When he opposed the invasion of Lebanon by Israel.

Nat Hentoff: I wrote against the invasion of Lebanon by Israel in 1982. Never received so many letters inviting me, showing me various ways to commit suicide expeditiously, on anything I’ve ever written.

Nick Hentoff: And I think it was in a motel on Long Island. And they weren’t serious rabbis who excommunicated him, but just another example of him willing to take an unpopular position with a core group of people that he felt comfortable with initially. And, well, Nat came from an immigrant community in Boston. And it was segregated by neighborhoods, so you had Jewish neighborhoods. You had Irish neighborhoods. You had Italian neighborhoods, something that you don’t see very much anymore, but back then, it was the way that all the different immigrant communities interacted with each other.

They had their own turfs, but in Nat’s house, for instance, his father immigrated to Boston from a town called Volkavichy, and it’s spelled various ways, but essentially exists today in Belarus. And it was a small-to-mid-size city with a Jewish community. It was part of the pale of the imperial Russia. His father came here at 15 by himself, and his brothers were already here. This is a town that was decimated during World War II. It was basically eliminated in the Holocaust. I have found a newspaper article from the New York Times that actually mentions the town and said there are 1,000 Jews left in the town.

It became a railroad hub that was used to deport all of the surrounding Jewish communities to Auschwitz. And so, from his father’s perspective, his father, everyone he knew growing up was destroyed in the Holocaust, and all of the extended family. His brothers and his father survived because they came to the United States, but everyone else with that surname was gone.

And when he arrived, when his father, Simon Hentoff, arrived in the United States, he immediately, when he turned 18, joined the Army, and was sent over to Europe in World War I, and was injured in a gas attack during one of the attacks. And he became a United States citizen when he was commissioned out of the Army, on the Army base. Then he was released from the Army after becoming a US citizen.

David Lewis: Nat always described himself as a Jewish atheist. So, I think that your characterization is spot on. Culturally, he identified as Jewish, but not religiously.

Nico Perrino: There was this great story or anecdote in one of his memoirs, where he described how his father, if he was reading the newspaper, and saw some sort of injustice brought upon a group or an individual, he would kind of mutter to himself, “Very un-Jewish, very un-Jewish.” The idea being that the Jews were on the side of the rights, the righteous, the oppressed people, and that’s the story of Nat Hentoff’s career, is that he’s always on the side of the little guy, of the oppressed, of those who have had injustice done unto them. Nick, his dad, though, was worried about Nat growing up, right? Nat spent time in jazz clubs. He was interested in civil rights. Didn’t he approach Nat’s doctor about that as sort of an ailment?

Nick Hentoff: Yeah. It’s really interesting because it’s sort of like a jazz singer phenomenon, the old film with Al Jolson, where you had a cantor, a rabbi, and his son wanted to sing the blues. His son wanted to sing a different tune from the religious songs that his father sang. In Nat’s case, he was interested in things that his father didn’t really understand. And I think it concerned him because he wanted him to be traditionally a success. He wanted him to go into a career that would provide a good life for him. And he just didn’t see how any of this jazz stuff was gonna produce anything that was gonna allow him to make a living or to raise a family, and it was just he was hanging out with jazz musicians.

And he was just not interested in things that good Jewish boys should be interested in. And so, he asked him to go into the family physician to check him out to make sure that he was okay. And it’s a hilarious letter that the physician wrote back, a very polite letter to the father, saying, “I’ve talked to your son, and the fact that he’s interested in civil rights, and he’s interested in jazz music is absolutely nothing to worry about. He’s gonna do just fine.” And of course, he did.

David Lewis: He saw a connection between Jewish cantorial music and jazz. He kept a collection of Jewish cantorial music, of LPs, and he always talked about how the cantor singing had the same cry as he heard in the jazz musicians.

Nat Hentoff: Jazz hit me hard when I was 11 years old, the first music that really got inside me. I was so excited by it. My family belonged to an orthodox synagogue, a shul, in Roxbury. Now, the shul had cantors, hazzans, and they were partially improvisatory, and they sang, largely, improvisations based on, of course, religious text. And the first time I heard music that made me feel inside that way, I was walking down Boston’s main street, and I heard a sound that got to me. And I rushed into the record store. “What was what?” It was Artie Shwa, a clarinetist, playing Nightmare.

David Lewis: And he said he told his friend Charles Mingus, the jazz bassist and composer this is the Jewish blues he played. He’d play the cantorial music for Mingus, and say, “This is the Jewish blues.”

Nick Hentoff: That’s the music I played for him as he was dying. I alternated between Billie Holiday and the cantorial music of his youth.

Nico Perrino: When I think of Nat Hentoff, I often associate him with New York City. He just seems like this quintessential New York character. He did spend his first 28 years in Boston, however. How does he end up in New York City?

David Lewis: He got a job, you know? He got a better job, you know? Nat was a hustler in the good sense of the word. He likes to work, and he needed to work, and he went where the jobs were. And so, he got a job writing, I think, for a magazine in New York. Picked up the family and moved.

Nico Perrino: You. And it was Down Beat, right? He got a job as a jazz journalist, but he wanted to break into more popular journalism, opinion journalism about broader political and social issues of the day. He had made a name for himself, of course, in jazz, right, Nick? But how did he find his way into more popular writing?

Nick Hentoff: When he was a kid, he and his father used to go to all the different synagogues in the neighborhood and listen to the cantorial music, and they would appreciate that music together. And that led to Nat, once he discovered the local jazz clubs, to hanging outside of the jazz clubs. And he would hang out religiously and get in just to listen to the music. And finally, when he was a very young man, he spoke very well. He was extremely articulate. He knew everything about jazz. He started doing what was essentially the first jazz blog, and it was a newsletter that they would type out on a typewriter, he and his partner in Boston.

And they would write gossip about the local jazz community. That got him a radio gig, and he started broadcasting live from the various jazz clubs. And some of these recordings still exist, and eventually, he got offered a job on Down Beat in New York, and he moved to New York. And that was a very rich environment for him.

And the beat scene and eventually the folk scene, and eventually rock and roll, was all boiling up out of Greenwich Village in New York, and that’s where he lived, and he knew everybody, and everybody knew him, and he was one of the few people in the ‘60s, who not only was writing — I mean, like, there are certain things that are important in people’s lives. One is music. Another is politics. And he agreed to write for free for the Village Voice in ’57 and ’58. And his only condition was that he wouldn’t write about music. He wouldn’t write about jazz.

He wanted to write about politics, but he continued to write about jazz for the rest of his life, and he continued to write about politics for the rest of his life. So, here are the two things that matter most to people, politics and jazz, and he’s writing about it constantly. He’s doing 30,000-word profiles regularly for the New Yorker. I mean, think about it. They talk about long reads nowadays, but that was a long read, 30,000 words in two parts in the New Yorker, Part 1 and Part 2.

At the same time, he’s doing the Playboy interview of Bob Dylan. At the same time, he was writing for every magazine that was published out of New York that dealt with progressive politics, and a lot having to do with music. And so, he became widely known in New York City, and as I said at the beginning of the program, everybody always used to ask me, “Are you related to Nat Hentoff?” And it wasn’t until I was graduating from college and I moved out to Saint Johns, Arizona, to work as a newspaper reporter, an hour south of the Navajo Indian Reservation, that I ran into my first people who had no idea who he was.

Nico Perrino: David, what was Nat’s approach to writing? You kind of see some of his unique peculiarities come through in your film. He’s surrounded by books. He’s still writing on a typewriter. How did he approach his craft, and what were the sort of stories that he gravitated to and that you found most interesting in your research for the film?

David Lewis: Well, he wasn’t a stylist. He wasn’t a high stylist. His voice was very straightforward and plainspoken. He said that he always had to have the lede in the first sentence of the article, first, and then everything else flowed from that. You know, I was mostly interested in the historical stuff, his famous early profile of Malcom X, meeting him in a diner up in Harlem. He respected Malcom. He respected his intellect, and they became, I wouldn’t say friends, but it wasn’t the last time that he interviewed him and communicated with him.

The Dylan stuff, in addition to the liner notes, there was a profile, a very early profile, in the New Yorker where Nat sat in on a recording session and profiled him. And that’s really where the Dylan myth started to take shape, was in that article, because Dylan told all these wild stories as part of his biography. And the New Yorker fact checkers, the famous fact checkers, missed a lot of it, or had a lot of it to get through. But, you know, I remember as late as the Obama administration, him writing articles critical of President Obama’s practice of using drones to kill Americans abroad who he felt were terrorists or enemies of the state.

He did a famous cover for the Village Voice, George W. Obama, and they had a profile where George W. Bush’s head morphed into Obama’s head. So, all through his career, it’s just exciting to pick up and read. I started the film with a friend of mine, the great journalist Tom Robbins. We were talking about what might be a good project for me, and he called me up when he got home that night. He said, “You know, I was just on the subway, and there was a college kid. He’s sittin’ there cross-legged on the subway platform, reading the Village Voice,” and he was reading Nat. And here’s this guy in his mid-‘80s, and the college kids are still reading him.

Nico Perrino: The tenure at Down Beat ended kind of on a sour note, didn’t it, Nick?

Nick Hentoff: Yeah, I believe so. It had to do with the hiring of a woman that the owners perceived, I believe, to be African American, and it turns out that she was actually Egyptian. Am I completely incorrect about that, David?

David Lewis: No, you’re correct. That’s right.

Nick Hentoff: And he just wouldn’t tolerate that. He found it particularly absurd at a publication that was writing about people that were creating music, who were, the majority of the jazz musicians at the time, were Black, African American.

David Lewis: It’s important when we talk about Nat as a jazz writer, he wasn’t just writing about it as playing music. He was writing about it as an art form. And he treated these musicians with the respect that they deserved, and he respected the amount of work that they put into it. He respected their knowledge of the music. He respected the history of the music.

And that really gave him entrée into the jazz community and to the musicians, who are famously not very good interviews, usually, and don’t like to talk to journalists that much. But Nat was a charter member of the community. He came up at Down Beat when jazz was really changing from popular music to more art forms and different styles of jazz. And Nat was really at the forefront of writing about that and recognizing it.

Nick Hentoff: And it’s interesting because, one of the things I found interesting, is that when you’re a jazz critic, it’s sometimes difficult to have close relationships with the jazz musicians because you’re gonna have to review their work critically, and so that doesn’t really foster close, personal relationships, if you’re gonna be honest about what you’re doing. And yet, he had some very close relationships with jazz musicians like Mingus, who just felt very close to him, and he was a color-blind person. Just absolutely, literally, he was a color-blind person.

He didn’t like pigeonholing people and believing that the only thing you can talk to with a Black person is jazz. And one of my favorite stories about him that he had in his memoirs is the time he was able to meet a former slave. He was a young man in Boston. He had a Black friend whose grandfather had been a slave, and was in his 80s or 90s, and who loved to read. He spent his days, the former slave, in the Boston Public Library, reading everything that he could lay his hands on.

And when Nat went over to meet him, he wanted to talk to him about the origins of music and jazz, and the guy only wanted to talk to him about reading the classics because he learned that he went to Boston Latin School with his grandson, and he wanted to know what he thought about the various classical poets and playwrights. He realized that the guy was dismissing him as an unserious person because all he wanted, all Nat wanted, to talk to him about was jazz. I think that was an important event for him, and it changed the way he dealt with people.

David Lewis: One of my favorite moments in the film was — it’s a very quiet moment — but where he’s interviewing Mingus, and he happens to be recording it. But they were old friends, and they were sitting in Mingus’s living room. And Mingus starts talking about a song that he was working on, and he starts singing it to Nat. It’s just a very quiet, sort of intimate moment between these two friends that really has always stayed with me.

Nico Perrino: David, what motivated Nat’s interest in free speech? You talk about how, in your documentary, free speech for Nat Hentoff is sort of a way of life, a way of being. How did that become a way of being for Nat? What were those early motivations?

David Lewis: Well, I think that antisemitism and the war had a lot to do with it. He equated American democracy with free speech. And he always talked about how jazz was kind of like the American democracy, with everybody playing, expressing themselves, with their own voices, but when it all came together, it was a full composition, like the American democracy. I think that he loved this country and loved its history, for all the criticism that he gave it, probably because of all the criticism that he had for the country.

Nick Hentoff: Well, you know, the American Civil Liberties Union was born out of the Espionage Act, and it was born out of the imprisonment of Eugene Debs and other anti-war activists during World War I. The Red Scare of the 1950s had a deep impact on Nat. I was talking to my mother just a couple of weeks ago.

My mother is 95 years old, and were talking about, she said, “You have no idea just the kind of atmosphere that existed in the 1950s,” where you walked into a store, and people had certain books that were under the counter, and that people, if you read a certain book, or a certain book was found on your bookshelf or in your academic office, you faced your life being ruined, being fired, and a little bit why FIRE was created as well. It started out as an academic defender of free speech. And for Nat, that had a deep impact on him. And for the rest of his life, he was a proselytizer of free speech.

He didn’t just write about it. He didn’t sit at home and talk about it. He went out on the road, like a preacher, preaching about it, and he would speak at hundreds of different college campuses and different little community groups. And I actually found this on eBay. And this one is a poster that’s from a college campus in the 1960s, and it says, “Nat Hentoff,” and the topic that he’s speaking on is, “Radical Alternatives After College,” right? And so, this one is a poster of his talk that he was giving in 1996 in West Virginia, of all places, Charleston, West Virginia, talking about free speech.

And up until he got into his 80s, he was just traveling all the time to different college campuses and different little community groups, particularly in communities where they’d had problems with censorship and people wanting to ban books. He was a big defender of librarians. He always defended librarians, and it didn’t mean just in the United States. He, controversially, was very critical of the old left for defending Castro’s oppression of librarians in Cuba.

David Lewis: The way that Floyd Abrams, a prominent 1st Amendment attorney, put it was Nat just didn’t talk about free speech or write about free speech. He used it. That’s what his career was based on.

Nat Hentoff: The American Nazi Party, which was doing reasonably well, decided to launch and organize Skokie, a part of Illinois. And there was a lot of controversy. Should they have the right to speech, these Nazis? And the ACLU leadership agreed with that, but not all the members or chapter heads. And I wrote about it as if I were Oliver Wendell Holmes, saying, “Of course they have a right to speak.” That was one of the times when I learned how to become very unpopular.

Nico Perrino: He was also, though, the subject of censorship in a couple of instances. So, in reading his memoirs, I was struck by how, when he was primarily interested in jazz, he taught a course at the Samuel Adams School in Boston. This was a school that was associated with some communists. That wasn’t really why he was there or what he was interested in, but they asked him to teach a jazz course, and so he did.

And because of that, I guess he became under the watchful eye of some of the McCarthyite folks in the legislature there, and maybe even the FBI. Nick, you would know better than I would, but I know that when he left Boston, he was worried that going to New York and leaving Boston might be complicated because of his class at the Samuel Adams School.

Nick Hentoff: That was a communist school. It was at least a deeply socialist school, and it was in the late ’40s that he started teaching there. And he was called before a local Un-American Activities committee, he felt he had cooperated to the extent that he cooperated and gave names, that he cooperated too much. I think he felt deep shame about that, and he vowed that he would never do that again.

And so, when he, in the ‘60s, started to draw the attention, when he was writing more and more about racial justice and about the civil rights movement, which he was very involved in, he was backstage at the March on Washington doing interviews, and those reel-to-reel tapes exist in a university library. They’ve never been published, or transcripts haven’t been prepared for them, or they haven’t been digitized, but I bet that would be very interesting.

He drew the attention of the FBI. Two FBI agents came to his office in New York City, and it wasn’t in the Voice. He had a private office, and they questioned his janitor in the building, and the janitor told him. And they came back, and instead of being cowed by that experience, and of not talking about it and not writing about what they were questioning him about, he did the exact opposite. He started on a tour of campuses, not only talking about his interview by the FBI, but talking about everything they didn’t want him to talk to.

Nico Perrino: Was the FBI interested in him because they thought he was a communist, or was it because of his civil rights advocacy, or was it just because he was associated with radical ideas? What caught their eye?

Nick Hentoff: They were afraid of radical communism, and they believed at the time that the civil rights movement was infiltrated by communists. They believed that anybody who supported it had communist leanings. So, it really was a vestige of the Red Scare.

David Lewis: By the time we got into the later ‘60s and the early ‘70s, and a lot of the FBI abuses of civil liberties were becoming exposed, Nat wrote about that a lot. There was a famous incident where a group of activists broke into an FBI office in, I think, I believe it was Philadelphia, Pennsylvania — is that right? — and stole all their files and started mailing them out to journalists. And Nat was the proud recipient of one of those packages, and that got him another visit from the FBI.

Nick Hentoff: I remember him interviewing Daniel Ellsberg in our living room.

Nico Perrino: For our listeners who aren’t familiar with Daniel Ellsberg, that is the guy who was responsible for the Pentagon Papers.

Nick Hentoff: That really drew the interest of the FBI because those were some of the country’s most sensitive, not only war secrets, the Vietnam War, but also nuclear secrets. Ellsberg released a great deal of. He used to be a nuclear planner, and he released a lot of secret documents about nuclear planning, with the idea of really opposing the proliferation of nuclear weapons and trying to prevent a nuclear war from ever taking place.

David Lewis: And Nat was an early critic of the Vietnam War. By ’67, ’68, he was already saying, “We’re committing war crimes in that country.”

Nico Perrino: So, he was a defender of librarians. He wrote a book, The Day Came to Arrest the Book. It has undertones that might speak to what’s happening today. He fought against McCarthyism. But he also fought for press freedom, going back to his early days as a student journalist at Northeastern University in Boston. He was an editor at that publication. And it really became a muckraking publication under his leadership.

Enduring lessons from Nat Hentoff’s 1982 ‘The Day They Came to Arrest the Book’

Nat Hentoff’s 1982 Young Adult fiction book, “The Day They Came to Arrest the Book,” follows high school student newspaper editor Barney Roth as he navigates writing about and advocating for his teacher’s right to teach Huck Finn.

They were investigating the board of directors, I guess, at the school. And he was fired for this. And he said, “Ever since the day of my defenestration by the administration, Carl Ell, the president, everyone’s free speech has been my business.” He said, “I should be grateful to Carl Ell for having given me a life’s work.” He said his obsession with the 1st Amendment is due to Carl Ell. James Madison came later.

Nick Hentoff: I recently had an opportunity to look at his senior yearbook. It describes, in the individual photographs, what the person was involved in throughout their career in college. And everything that he was involved in, a lot of it involved the newspaper. It shows him starting out as a writer for the newspaper and becoming the editor. But then, if you flip to the page for the newspaper that year, he’s nowhere to be found. He’s not in the editorial board. And that’s the reason why is because in his senior year, he was kicked off of the editorial board by the president of the university.

Nico Perrino: And the university, though, didn’t they give them an honorary degree later in life? He thought it was kind of funny.

Nick Hentoff: I think they did. He was always an excellent student. He was very smart and always got excellent, excellent grades.

Nico Perrino: Yeah, it might not have been an honorary degree. I know he also received an award as a student because he got excellent grades, and the president, Carl Ell, refused to shake his hand or give him the award, which I guess was the tradition at the time. But Nick, I want to ask you what you think Nat would make of the current client for free speech? In my mind, again, he’s the quintessential civil libertarian, so I’m always asking myself, “What would Nat Hentoff say about this controversy, or this issue?”

Nick Hentoff: Somebody once asked him what was the principle motivating motivation that he used to do the kind of work that he did, and he had a one-word answer. And that was “rage.” He got angry, and the one thing that really made him angry, and it makes me angry too, is cruelty. And we’re seeing a lot of unbridled cruelty, and it’s just breaking my heart, and it would’ve broken his heart too. He would’ve been very upset about it.

Every day, I mean, it’s hard to — you want to avoid the news because every day, it’s not just about policy differences anymore. It’s about destroying people for no good reason, innocent people who haven’t done anything wrong, and they’re just being torn apart by this administration, or current administration, and he would’ve been very angry about that. It would’ve surpassed any political issues or policy disagreements for him. It’s just not the way that you treat people.

Nico Perrino: David, did you see that rage in Nat Hentoff when you were profiling him in his 80s? Was it still there in his latest years?

David Lewis: Well, yes, free speech. I just want to say, Nick, that that was beautifully said. I couldn’t say it any better myself, but I can tell you that one time I wanted to — he didn’t get out of the apartment much at that age, when I was making the film, and I wanted to film him going to the barber shop down the street, because I thought it would be a nice scene, and have him talk to the barber who had been doing his hair for 40 years or so.

And we set it all up, and I booked the camera crews and called him the night before, or he called me the night before, and said, “I’m not gonna do it. I don’t wanna do this.” And he got really mad at me, and he started yelling at me, and so I started yelling back at him. And I finally convinced him to do it, and afterwards, he said, “I’m really glad we did that.” So, yeah, he still had that rage, in little things and large.

Nico Perrino: You had a hard time actually getting a hold of him to do the documentary, right? He wouldn’t return any of your — you had to find his phone number or something, in the phone book?

David Lewis: I kept calling him up and saying, “I’m doing a documentary. I want to do a documentary.” He’s like, “That’s great. That’s great. I’m really busy now. Can you call me in a couple of weeks?” And I’d hang up, and I’d call him later, and same story, like two or three times, and finally, I just wrote him a letter, and I pleaded. As Nick mentioned earlier, he doesn’t use email, so I put it in the snail mail, walked up to the corner, and put it in the mailbox, and a week later, he called me. He said now he was ready to do it.

Nick Hentoff: He was also reluctant to go to the movie premiere. Do you remember that, Dave?

David Lewis: Yeah, yeah.

Nico Perrino: Why is that?

Nick Hentoff: Well, because towards the end, he had a very hard time walking. He had severe osteoporosis, and he took very short steps. And he didn’t like using a wheelchair. He didn’t like being put in a wheelchair and wheeled around. In fact, he refused it, and so if you were trying to help him walk, it would go at a snail’s pace. And so, it probably took us half an hour to get from the car down to the theater and into the seat, but he was really happy that he went.

He saw a lot of old friends, and he really enjoyed the movie, and it was just beautiful. He was very grateful, David, that you were able to make that movie, and it was a beautiful movie. It really affected him, and I wanted to mention to you about the rage thing, and I’ll tell you, for the last year, about the last year of his life, maybe, but the first, the year of 18 months, I started co-writing the column for him, because it became much difficult for him to read easily.

And we were still writing about Obama, even during the 2016 campaign. We came up with a title for one of the columns, and the title of the column was pretty provocative. It was, “Why is Obama Still Killing Children?” And it had to do with drone attacks in Afghanistan.

Nico Perrino: How did his liberal peers at the Village Voice and some of these other publications see that sort of criticism of a liberal icon, in this case, President Barack Obama, or even going back to the ‘80s, his prolife writings? Was he ostracized for that? Or was it just people kind of assumed that Nat Hentoff was gonna march to his own beat or be out of step?

Nick Hentoff: Yeah, I think it was generational by that point. By the time that he started writing about prolife issues, and also about issues involving disabled disagreed and the disabled, because that’s also part of the Seamless Garment, and there were some children that had severe developmental disabilities at birth.

And the question was whether or not they should be allowed to die or not. And there were some epic court battles at the time between parents and hospitals, and individual parents, involving babies with spina bifida, and he started to delve into medical research deeply. He would do his own research, and he knew more about the subject than many doctors. He did the research. He read the research that talked about at what point pre-born babies, fetuses, feel pain.

And he did the research about what the life expectancy was, and what the quality of life was for people who suffered from spina bifida, and he just follows the Seamless Garment in believing that nobody should be deprived of their life. He especially didn’t like it when they were deprived of their fundamental rights without due process, which is what was happening in a lot of these situations.

Nico Perrino: Did he have a politics? If you asked him what his politics were, did he have a way to describe it?

Nick Hentoff: I think he felt most comfortable in a libertarian ideology.

Nico Perrino: Okay.

David Lewis: That’s the way he described himself. He would never vote for or support the nominee for president of a major political party. That’s for sure. I think he told me that in 1968 he voted for Dizzy Gillespie, who was running for president at the time.

Nick Hentoff: His affinity for libertarian ideology was more of an individual rights affinity, and not an economic affinity. He believed in a social safety net. He believed in the rights of labor unions to organize, very, very deeply.

David Lewis: Yes.

Nick Hentoff: And since he organized a labor union at his candy store he worked at when he was a pre-teen, he was an iconoclast. He was somebody who, anybody else, would’ve been deeply conflicted and offering from cognitive dissonance, but it was a beautiful mix in Nat Hentoff because he believed in individual rights. He believed in treating people fairly. He believed in caring for the poor and sick, and he wouldn’t stand for it when people didn’t do that.

David Lewis: He called himself a lower-case libertarian, a lower-case l, to dissociate himself from the organized political party.

Nico Perrino: Nick, your brother, Tom, mentioned that Nat was a line drawer, not a balancer. I had never heard that phrase before. But it really captures something about a lot of civil libertarians. And I want to see if you might be able to unpack what that means. What does that say about your father’s approach to the issues?

Nick Hentoff: Tom and I are both lawyers, and balancing act is a legal term they use in constitutional litigation. Courts are always wanting to balance the rights of people, and they try and do their best in resolving difficult conflicts by balancing the rights, and there are different tests for what should happen in any given situation. And Nat was a line drawer in the sense that he had principles, and he was uncompromising about them. And so, that’s why he was a free speech absolutist. You couldn’t get him to admit there was any form of free speech that, if it didn’t involve violence against other people, then everybody had a right to say it.

Nico Perrino: And he didn’t believe in defamation law, right, David?

David Lewis: He didn’t believe in defamation law, libel suits. I don’t think he really believed in copyright, either, and Nick’s brother, Tom, is a copyright lawyer.

Nick Hentoff: It’s interesting. I think the majority of people want to be liked, and they care very deeply about what other people think about them. That results in a form of self-censorship, and people will censor themselves in order to be accepted in any given community. People tend to want to avoid conflict. They don’t want it, and also, they tend to be in jobs where you can get in a lot of trouble by not being a team player. It’s the easiest way for somebody to get fired in a business is by not being a team player, or not being successful, and being relegated to a desk in an obscure office somewhere for most of your life. One of the typical examples of that is people who grew up in the Soviet Union.

Nico Perrino: Yeah. He wrote that he loved his job. He said, “To get paid for your opinions, the more controversial the better, must be the best of all possible jobs. Citizens sit down to breakfast and open the paper to applaud you,” or, he says, “Better yet to roar at you and spill their coffee all over their pants. What a life,” he concludes. So, it was quite a life, David. Yeah, if you want to speak to that, but I’m also curious to hear what you think his most important legacy is.

David Lewis: Well, let me just say this first. We spoke earlier about Francis Sweeney, who published the newsletter in Boston, the muckraking newsletter, and he wrote about her in the same book. He wrote, “She was the one who taught me the pleasures of being out of step.” And that’s where I got the title for the film, and I really do think there was a certain joy for him in being out of step. And that’s where that came from. His legacy? Oof. I mean, we have jazz as we know it today. We probably wouldn’t know it the way we know it today without Nat’s understanding of it and his ability to communicate it to us.

We have a whole era of speaking truth to power through the ‘60s and ‘70s that Nat was instrumental in creating, changed the course of this country. We haven’t really talked about alternative journalism and what alternative journalism is, but he was there at the creation and helped to create it. It’s a form that endures today.

Nick Hentoff: It’s the dominant form of journalism today, I think. You had Jim Acosta, who has a very successful Substack. How many people can we talk about right now who have very successful Substacks, which is basically alternative journalism? You do what you want to do, and people support you for it.

The first person to really do that successfully was I.F. Stone. He was the first person to really make a living at publishing a newsletter that was mimeographed and mailed to people. What was that newspaper? There was a folk newspaper that published all of Dylan’s first songs, but it was mimeographed and mailed out to people. And some of the musicians that got it when they were kids were like Janis Ian, who had a different name back then, and her first songs were published in that particular publication.

So, we’ve gone from people mimeographing their own newsletters, like the first blogs, to corporate media, and you can only really get on television, or you can only really get into the papers, if you worked for a corporate news organization, to now, we’re back to people are really finding themselves and getting real followings doing their own things on Substack and other alternative platforms.

David Lewis: It’s really about dissent, right? It’s all dissent, and it’s very easy for dissenters to become the establishment over a period of time. But Nat was always at the forefront of dissent, all through his career.

Nick Hentoff: I think his legacy is simply that if you see something that’s wrong, you’ve got to stand up, and you’ve got to talk about it for as long as you can, as loudly as you can, and as eloquently as you can. And I think that that is something that he accomplished very well in life and was very successful at it.

David Lewis: His response to speech that he didn’t like was always more speech.

Nico Perrino: Well, David Lewis, Nick Hentoff, I think that’s a beautiful place to end this conversation. I thank you both for joining us today.

Nick Hentoff: Thank you for having us.

Nico Perrino: And David, before we sign off, how can folks watch your documentary? It’s not available on any of the streaming platforms, is it?

David Lewis: Well, you can now get it on OVID.tv, which is a streaming platform that is devoted exclusively to documentaries. And they came to me last year, and asked if they could have it, and I’m very happy that people can find it there.

Nico Perrino: I think I have some ways that we might be able to get it onto some other streaming platforms. Maybe you and I can connect about that offline. But in the meantime, for folks who are looking for more about Nat Hentoff, and I’m tellin’ you, you got to learn more about this guy. He’s brilliant. He’s interesting. He’s funny. He’s got a beautiful voice, one of the most beautiful voices I’ve ever heard.

David Lewis: A radio voice.

Nico Perrino: A radio voice, free speech, but you could and should watch the documentary that David made, The Pleasures of Being out of Step, but you should also read his books. I think he published something like 30 books, non-fiction and fiction, throughout his lifetime. I’ve got a couple of sitting right here next to me, Speaking Freely and Boston Boy are two of the more prominent memoirs. Speaking Freely, the poster for it is sitting behind Nick right now for those watching on video. But also, if you’re big into the free speech world, Free Speech for Me — But Not for Thee. I think the book was published in 1992, is a classic, and the title has become a meme in the free speech world.

David Lewis: And some classics on jazz as well, books on jazz, devoted exclusively to the voice of the musicians themselves. He kept his own voice out of it.

Nick Hentoff: It’s interesting because he was nominated a couple of times for a Pulitzer Prize. And he would always submit that his editors would always submit his political work for the Pulitzer. And my mother believes that if they had submitted his jazz criticism, he would’ve won a Pulitzer in criticism. They never did. They didn’t do that.

Nico Perrino: The path not taken. Well, folks, I am Nico Perino, and this podcast is recorded and edited by a rotating roster of my FIRE colleagues, including Bruce Jones, Ronald Baez, Jackson Flegal, and Scott Rogers. The podcast is produced by Emily Beaman. To learn more about So to Speak, you can subscribe to our YouTube channel or Substack page, speaking of Substack, both of which feature video versions of this conversation. You can follow us on X but searching for the handle FreeSpeechTalk. And you can send us feedback at SoToSpeak@theFIRE.org.

Again, that is SoToSpeak@theFIRE.org. Every other week, I ask you if you enjoyed this episode, please leave us a review on Apple Podcast, Spotify, or wherever else you get your podcast. Reviews help us attract new listeners to the show. And until next time, I thank you all again for listening.

[End of Audio]