Table of Contents

Why Even Nazis Deserve Free Speech

This article appeared in Politico.

The events in Charlottesville last weekend have provoked understandable fear and outrage. Potential sites for future “alt-right” rallies are on edge. Texas A&M University, the University of Florida and Michigan State University have all decided to cancel or deny prospective events by white nationalist Richard Spencer. All cited safety concerns. All raise serious First Amendment issues.

Even though we’ve been called “free speech absolutists”—sometimes, but not always, as a compliment—we will not pretend that Spencer’s speaking cancellations make for a slam-dunk First Amendment lawsuit. Yes, hateful, bigoted and racist speech is fundamentally protected under the First Amendment, as it should be. However, if we’re honest about the law, we have to recognize that Spencer faces tough—though not insurmountable—legal challenges.

First, he is not a student at any of the aforementioned universities and was not invited to the campuses by students or faculty. He was seeking space on campus that is available to the general public to rent out. In at least some cases, courts have found that public colleges have a somewhat freer hand to regulate the speech of non-students on campus who are not invited by students or faculty.

Second, although a general, unsubstantiated fear of violence is not enough to justify cancelling an approved speaking event, recent violence in Charlottesville and the fact that one of the organizers of the Texas A&M rally used the promotional tagline “TODAY CHARLOTTESVILLE TOMORROW TEXAS A&M” make security concerns more concrete, at least in the short term. The more concrete the security concerns are, the easier it is to justify the cancellation or denials.

Third, as David Frum, Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern point out, judges might decide cases differently when protesters are liable to show up brandishing guns, as happened in Charlottesville. Bad facts make bad law, so the saying goes. The general legal standard now is that if a public college opens itself up to outside speakers, it cannot engage in viewpoint discrimination. Most cases of prior restraint censorship will fail in court under this standard. But in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy in Charlottesville, judges may look differently at these facts.

And that should trouble us: If a court decides in favor of the prior restraints, it could set a precedent that would do considerable harm to the free speech rights of speakers, students and faculty far beyond Spencer.

But what happens in a court of law is one thing. What happens in the court of public opinion is perhaps more important. As the famous jurist Learned Hand once said, “Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it.”

And, unfortunately, there is evidence that freedom of speech needs a pacemaker.

If your social media newsfeed doesn’t provide ample anecdotal evidence that free speech is suffering a public relations crisis, look to the polling: A recent Knight Foundation study found that fewer than 50 percent of high school students think that people should be free to say things that are offensive to others.

The New York Times opinion page, for its part, has run three columns since April questioning the value of free speech for all, the most recent imploring the ACLU to “rethink free speech”—the same ACLU that at the height of Nazism, Communism and Jim Crow in 1940 released a leaflet entitled, “Why we defend civil liberty even for Nazis, Fascists and Communists.” The ACLU of Virginia carried on this honorable tradition of viewpoint-neutral free speech defense in the days before the Charlottesville protests. However, the Wall Street Journal reported this week that the ACLU “will no longer defend hate groups seeking to march with firearms.”

And how is the birthplace of the 1960s free speech movement faring? In the wake of the riots that shut down alt-right provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos’ speech at the University of California, Berkeley on February 1, multiple students and alumni wrote that the violence and destruction of the Antifa protests were a form of “self-defense” against the “violence” of Yiannopoulos’ speech. Watching videos of the protest, it is fortunate nobody was killed.

What’s to account for this shift? One of our theories is that this generation of students comprises the children of students who went to college during the first great age of campus speech codes that spanned from the late 1980s through the early 90s. This is when colleges and universities first began writing over-broad and vague policies to regulate allegedly racist and sexist speech. Although that movement failed in the court of law, these codes have stubbornly persisted, and the view that freedom of speech is the last refuge of the “three Bs”—the bully, the bigot and the robber baron—found a home in classrooms.

When we speak on college campuses, our explanations of the critical role the First Amendment played in ensuring the success of the civil rights movement, the women’s rights movement and the gay rights movement are often met with blank stares. At a speech at Brown University, in fact, a student laughed when Greg pointed out that Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall was a steadfast defender of freedom of speech––as if it were impossible for a black icon of the civil rights movement to be a free-speech champion.

However, we don’t fault students for holding these opinions. The idea of free speech is an eternally radical and counterintuitive one that requires constant education about its principles. Censorship has been the rule for most of human history. True freedom of speech is a relatively recent phenomenon. It perhaps reached its high point in the United States in the second half of the 20th century.

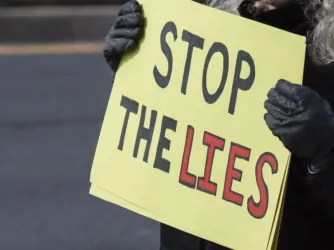

Most Americans claim that they venerate free speech in principle. So do most world leaders. Even censorial dictators like Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan sometimes feign support for it. Despite this, it’s common for people to have their exceptions in practice: their “I believe in free speech, but …” responses. But even the “free speech, but …” responses seem to be falling out of favor. In the last few years—and especially after Charlottesville—we have observed increasing squeamishness about free speech, and not just in practice; also in principle.

So how do we respond to the calls for censorship after Charlottesville?

For most of our careers, the charge “what if the Nazis came to town?” has been posed as a hypothetical retort to free speech defenses. (Godwin’s law extends to free speech debates, too.) But the hypothetical is no longer a hypothetical: In Charlottesville, neo-Nazis carried swastikas through the streets and revived the Hitler salute.

If you were to listen to scholars like Richard Delgado, the response should be to pass laws, to put people in jail, to do whatever it takes to stop the Nazi contagion from spreading. It’s a popular argument in Europe and in legal scholarship, but not in American courts.

There are a few problems with this response that free speech advocates have long recognized. For one, it doesn’t necessarily work; since the passage of Holocaust denial and anti-Semitism laws in Europe, rates of anti-Semitism remain higher than in the U.S., where no such laws exist. In fact, the Anti-Defamation League found that rates of anti-Semitism have gone down in America since it first began measuring anti-Semitic attitudes in 1964.

What’s more, in the 1920s and 30s, Nazis did go to jail for anti-Semitic expression, and when they were released, they were celebrated as martyrs. When Bavarian authorities banned speeches by Hitler in 1925, for example, the Nazis exploited it. As former ACLU Executive Director Aryeh Neier explains in his book Defending My Enemy, the Nazi party protested the ban by distributing a picture of Hitler gagged with the caption, “One alone of 2,000 million people of the world is forbidden to speak in Germany.” The ban backfired and became a publicity coup. It was soon lifted.

We cannot forget, too, that laws have to be enforced by people. In the 1920s and early 30s, such laws would have placed the power to censor in the hands of a population that voted in large numbers for Nazis. And after 1933, such laws would have placed that power to censor in the hands of Hitler himself. Consider how such power might be used by the politician you most distrust. Consider how it is currently being used by Vladimir Putin in Russia.

What does history suggest as the best course of action to win the benefits of an open society while stemming the tide of authoritarians of any stripe? It tells us to have a high tolerance for differing opinions, and no tolerance for political violence. What distinguishes liberal societies from illiberal ones is that liberal societies use words, not violence or censorship to settle disputes. As Neier, a Holocaust survivor, concluded in his book, “The lesson of Germany in the 1920s is that a free society cannot be established and maintained if it will not act vigorously and forcefully to punish political violence.”

But we should not be so myopic about the value of freedom of speech. It is not just a practical, peaceful alternative to violence. It does much more than that: It helps us understand many crucial, mundane and sometimes troubling truths. Simply put, it helps us understand what people actually think—not “even if” it is troubling, but especially when it is troubling.

As Edward Luce points out in his excellent new short book The Retreat of Western Liberalism, there are real consequences to ignoring or wishing away the views that are held by real people, even if elites believe that those views are nasty or wrongheaded. Gay marriage champion and author Jonathan Rauch reminds us that in the same way that breaking a thermometer doesn’t change the temperature, censoring ideas doesn’t make them go away—it only makes us ignorant of their existence.

So what do we do about white supremacists? Draw a strong distinction between expression and violence: punish violence, but protect even speakers we find odious. Let them reveal themselves.

As Harvey Silverglate, a co-founder of our organization, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, says, it’s important to know who the Nazis are in the room.

Why?

Because we need to know not to turn our backs to them.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

Free speech in Trump 2.0

Podcast

The federal charges against Don Lemon raise serious concerns for press freedom

The American people fact-checked their government