Table of Contents

UK police threaten to prosecute speech from ‘further afield online’ while internet crackdowns and blackouts strike around the world

This year, FIRE launched the Free Speech Dispatch, a regular series covering new and continuing censorship trends and challenges around the world. Our goal is to help readers better understand the global context of free expression. The previous entry covered how tech companies have responded to censorship demands, how speech is faring in the U.K., and the punishment of a dual U.S.-Saudi citizen. In this entry, we’ll look at the busy past few weeks for free speech across Asia, South America, and Europe.

Want to make sure you don’t miss an update? Sign up for our newsletter.

Censorship concerns spiral after UK riots

In the midst of unrest, police and politicians often wrongly look to censorship as a quick fix. As I wrote earlier this month, that’s the well-worn path the U.K. headed down in recent weeks, as riots popped up across England and Northern Ireland in response to viral false claims that the alleged murderer responsible for a July 29 knife attack was an asylum seeker.

While police must act against threats, violence, vandalism, and other crimes, they should be careful to protect free speech while cracking down on illegal conduct. Unfortunately, officials are not inspiring confidence about their ability to do so.

Concerns about free speech have rapidly escalated in the aftermath of these riots, with warnings from the Crown Prosecution Service against inciting hatred and “online violence” and a follow-up from the U.K. government’s X account telling internet users, “Think before you post.”

Arrests over online posts are underway, with “dedicated police officers who are scouring social media,” searching for users posting or resharing material about the riots.

But as with many censorship controversies these days, the effects aren’t necessarily limited to the originating country’s borders. In an Aug. 7 interview, Metropolitan Police Commissioner Mark Rowley suggested police are also looking at online speech outside of the U.K.

“We will throw the full force of the law at people,” Rowley said. “And whether you’re in this country committing crimes on the streets or committing crimes from further afield online, we will come after you.”

European Commissioner Thierry Breton jumped into the fray as well, soon after writing a letter to Elon Musk “in the context of recent events in the United Kingdom” and ahead of Musk’s Aug. 12 interview with Donald Trump. Breton urged Musk to “promptly ensure the effectiveness of your systems and to report measures” to Breton regarding X’s compliance with the Digital Services Act, the European Union’s worrying internet regulation law. Breton warned that his team was “monitoring the potential risks in the EU associated with the dissemination of content that may incite violence, hate and racism in conjunction with major political — or societal — events around the world.”

But the European Commission distanced itself from Breton’s letter, noting that President Ursula von der Leyen did not sign off on it and that the “timing and the wording of the letter” were not approved. While this response threw some cold water on Breton’s efforts, this will likely not be the last we hear on this front from either the U.K. or the EU in the coming months.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in Europe . . .

A ruling on speech issues in Germany is cause for concern, too. On Aug. 6, a Berlin court found German-Iranian national Ava Moayeri guilty of “condoning a crime” for leading protesters in a chant of, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” at a rally last October. Speech at pro-Palestinian protests has faced increasing restrictions in Germany since Hamas’ Oct. 7 terrorist attack on Israel. As I covered in a previous edition of the Free Speech Dispatch, Berlin police even forbade protesters from speaking foreign languages at protests this year.

And in a not-so-tall tale out of Italy, a court ordered journalist Giulia Cortese to pay €5,000 in damages to Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni. Cortese was acquitted for a tweet in which she posted a photo comparison of Meloni and Benito Mussolini, but she was convicted of defamation for two tweets in which she mocked Meloni’s 5’ 3” height, which the judge called “body shaming.” Cortese had tweeted that Meloni is “a little woman,” and, “You don’t scare me, Giorgia Meloni. After all, you’re only 1.2 metres (4 ft) tall. I can’t even see you.”

The Paris Olympic games suffer censorship stumbles

The expressive choices in France’s opening ceremony sparked plenty of debate, but people also scrutinized what athletes could not express. At issue was France’s prohibition on any religious symbols worn by anyone engaged in civil service, which includes athletes representing the country who wear hijab. France did not extend this ban to other countries’ athletes, but the restriction highlights the broader tension between secularism and religious freedom in the country.

Some attendees at the games also ran into trouble over their support of Taiwan’s team, which competes under the name “Chinese Taipei.” The IOC disallows the display of “any political messaging” and apparently considers the simple use of the name “Taiwan” political in nature. This rule led to the confiscation of multiple fans’ signs, including one that said, “Let’s go Taiwan,” and another simply displaying the country’s name. The incident offers a peek into the messy and fraught business of drawing lines around political speech, and even of defining what is “political” in the first place.

Lastly, Algerian gold medalist boxer Imane Khelif announced the filing of a criminal complaint with French authorities over “acts of aggravated cyber harassment” from internet users over her gender. Khelif’s lawyer, Nabil Boudi, suggested individuals outside France would be named, including J. K. Rowling, Elon Musk, and Donald Trump. But Boudi also said that France’s “prosecutor’s office for combating online hate speech has the possibility to make requests for mutual legal assistance with other countries” and has agreements with the United States to combat online hate speech. It’s unclear what U.S. office or agreements Boudi is referring to, or what mechanisms he thinks French prosecutors would use to pursue Americans if they are ultimately named in the complaint.

Internet censorship, takedowns, and blackouts across the world

The internet speech issues at play in the U.K. and the EU were just a drop in the bucket this summer. In countries around the world, authorities made efforts to block websites, online speech, or internet access generally.

- In late July, Bangladesh shut down the internet and mobile networks for days at a time in an attempt to tamp down on widespread anti-government protests originating from a student-led backlash against the quota system in civil service employment. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina ultimately resigned and fled the country.

- Pakistan is installing a new internet firewall in the country to control content and traffic online. The firewall, obtained from China, “can give Pakistani authorities information about an individual user’s online activities and where they are operating from, allowing for targeted monitoring.” Since its deployment, the firewall has led to mass internet slowdowns.

- Just a couple of weeks after claiming victory in a presidential election he appears to have definitively lost to challenger Edmundo González, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro announced a 10-day block of the social media platform X within the country on Aug. 9. Maduro also instituted a program that he calls “Operation Knock Knock,” which includes security officials “going door-to-door to detain those with links to the protests or the opposition.”

- Indonesian authorities blocked privacy-protecting browser and search engine DuckDuckGo in the country in response to objections about the availability of porn and gambling material. VPNs are reportedly next on the chopping block.

- The Turkish government temporarily banned Instagram early this month after accusing the platform of blocking posts commemorating the death of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh. The nine-day ban ended “after the company agreed to cooperate with authorities to address the government’s concerns.” That doesn’t mean you can freely talk about the ban though — a woman was arrested last week “on charges of inciting hatred and insulting the president” after she objected to the Instagram ban. She joins thousands of others who have been investigated or prosecuted for insulting President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

- Singapore is mulling a temporary ban on “deep fakes” ahead of its general elections this autumn. Earlier this year, South Korea instituted a 90-day ban on AI-created material before elections in the country.

- Over the weekend, X announced the closure of its offices in Brazil, citing the company’s long feud with Judge Alexandre de Moraes over censorship orders from the country’s Supreme Court. Moraes threatened fines and the arrest of X’s representatives in the country if it failed to remove content flagged by the court. The platform will, however, remain live in Brazil.

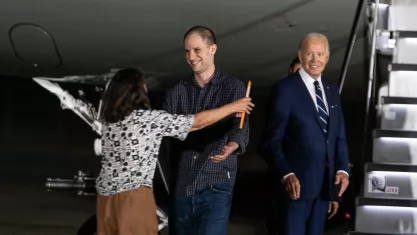

Evan Gershkovich released, but the situation in Russia remains grim

First, the good news: Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich reached the end of a nearly year-and-a-half long saga beginning with his detainment in March 2023. In mid-July, Gershkovich was convicted on trumped-up espionage charges and sentenced to 16 years in prison in Russia. But early this month, Gershkovich was released back to the U.S. in a historic prisoner swap that included other Americans and political prisoners.

Now for the bad news. Repression continues at a rapid pace within Russia, and only days after Gershkovich’s release a court sentenced Russian-American beautician Ksenia Karelina to 12 years in prison for treason. Karelina was first arrested in February while traveling to the country to visit family. She was accused of “providing financial assistance to a foreign state in activities directed against the security of our country” after agents searching her phone found that she had donated $51.80 to “a U.S.-based nonprofit that helps children and elderly impacted by the war in Ukraine.”

Freedom is on a continuous decline in Hong Kong

Journalists may not be able to rely on their employers for support

Despite Gershkovich’s release, it’s not all been rosy news for press freedom at the Wall Street Journal. In mid-July, reporter Selina Cheng announced she’d been fired from her position at WSJ for a troubling reason: her election as chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association. Cheng says her supervisor at the international desk in London warned her to drop out on the eve of the election, claiming the position would be “incompatible” with her job. Her supervisor also told her to abandon her other work with the press freedom association. Within a month of the election she was notified of her firing, which an editor said was due to restructuring, but Cheng believes is directly linked to her refusal to abandon press freedom advocacy in Hong Kong.

Cheng’s situation is apparently a common one — other journalists working at international outlets reported fearing repercussions from outlets that don’t want to risk retaliation by Chinese or Hong Kong authorities. As China Media Project writes, journalists in Hong Kong now need to challenge “both an increasingly authoritarian government and their own employers, based in the West and nominally committed to liberal principles.”

Freedom of expression faces challenges on other fronts in Hong Kong, too. In July, the Hong Kong Book Fair organizer warned multiple exhibitors that they could not sell some book titles due to “complaints.” The books, including Allan Au’s “The Last Faith” and one about children who emigrated from Hong Kong, reportedly contained undisclosed “sensitive content.” And later that month, a man was found guilty of insulting the Chinese anthem at a volleyball game last summer. He had reportedly covered his ears during the anthem and instead sang “Do You Hear the People Sing” from the musical “Les Misérables,” and also told police he “did not like the China team.”

Lèse-majesté law traps Thailand in cycle of repression

Jail sentences for offenders of Thailand’s lèse-majesté law, which bans insults to the country’s monarchy, continue to accumulate. Activist Parit “Penguin” Chiwarak, believed to have fled the country, was sentenced in absentia to two years in prison for Facebook posts he made in 2021. Chiwarak is facing 25 separate lèse-majesté charges in total. Lawyer and activist Arnon Nampa, facing 11 counts of lèse-majesté violations in total, was also sentenced over social media posts calling for reform of the country’s royal insult laws.

But perhaps most notable was the retaliation against the Move Forward Party, a popular political party that was just banned by Thailand’s Constitutional Court for its efforts to reform the country’s lèse-majesté law. The court claimed the reform campaign constituted an attempt to overthrow the constitution and also handed down a 10-year political activity ban on the party’s senior leadership. The party has since reformed into the People’s Party, but dozens of its members risk bans as well for their involvement in previous lèse-majesté reform efforts.

Polish metal band resolves blasphemy allegations

I’m glad to continue the trend of finishing these dispatches with some good news. This time, it’s from Poland, where metal band Behemoth has announced that the Regional Prosecutor’s Office of Gdansk is dropping the blasphemy case against the band. Behemoth has faced multiple blasphemy cases since 2017 over T-shirts it sold featuring artistic revisions to the country’s coat of arms. The band plans to make the shirts available for purchase again.

Rock on.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

Fandom’s lighthouse in a sea of censorship

FIRE statement on Stephen Colbert’s James Talarico interview and continued FCC pressure

Deep dive into New York’s proposals to ban demonstrations near houses of worship