Table of Contents

Author identity and the politics of suppression in today’s publishing world — First Amendment News 402

First Amendment News is a weekly blog and newsletter about free expression issues by Ronald K. L. Collins. It is editorially independent from FIRE.

The cancel culture crowd is alive and active in the commercial and academic publishing worlds, so don’t dare say what all know: The racial or gender identity of an author can kill a book regardless of its merit.

The animating idea behind such suppression is twofold: First, only people in a certain group can write about that group. Second, publishers must be more active in recruiting minority, LGBTQ+, and women authors. While something might be said for these “liberal” arguments, the problem is that such publishing mindsets seem to be wildly out of control. There appears to be no brake on the suppression train when it comes to author identity. This do-it-but-never-speak-it attitude is becoming ever more commonplace in the publishing world. Too many literary agents tolerate it, too many prominent editors covertly endorse it, and numerous university presses secretly celebrate it.

The author-identity suppression psyche

If you would like to know the psyche of the author-identity suppressor, simply consider a news item from last year involving a City University of New York student campaign to cancel an Emmett Till opera written by a white playwright. According to an article in The New York Post, a “petition to cancel a CUNY school production of an opera about Emmett Till written by a white woman was gaining steam Saturday. More than 11,000 people had signed the appeal to close the curtains on ‘Emmett Till, A New American Opera’ at John Jay College’s Gerald W. Lynch Theatre next week.”

Related

- Michael Andor Brodeur, "Whose song is this to sing? A new opera about Emmett Till faces scrutiny and protest," The Washington Post (March 22)

- Editorial, "Hear the opera: The ignorant, pernicious attempt to cancel ‘Emmett Till’ at CUNY’s John Jay College," New York Daily News (March 22)

Among others, one problem with author-identity suppression is that it conflates its mission with racial or cultural exploitation — which is a different matter. To commercially exploit the work of a class of people, and to do so along racial lines, is not synonymous with a work that is sensitive to the plight of racial oppression.

Enter the novelist Richard North Patterson and his author-identity battles (hat tip to Nadine Strossen for bringing this to my attention):

Richard North Patterson is an acclaimed novelist. He has authored some 22 novels, 16 of which were New York Times bestsellers. But all of that proved to be of little moment when he tried to cross the author-identity divide and write a novel about the trial of an 18-year-old black voting rights worker. The novel involves the accidental but fatal shooting of a racist white police officer during a late-night traffic stop in rural Georgia. As Patterson wrote in an article published in The Wall Street Journal on April 21, 2023:

I traveled to [Georgia], interviewing over 50 people, including many Black Georgians immersed in the problems of race: voting-rights activists, politically engaged ministers, community leaders, civil-rights and defense attorneys, politicians, law enforcement officers and ordinary citizens. Because my novel also portrays my principal female character as a senior at Harvard in 2003, I interviewed three Black women who attended Harvard around that time.

But when it comes to “white on black” — or “white appropriation” — too often merit does not matter and research does not count for much if the author’s identity does not match up with his or her racial subject matter. Here is how Patterson explained his plight:

My agents warned me that I was asking for trouble with major publishers, and I was acutely aware of the risk — most famously exemplified in 2020, when Jeanine Cummins, the white author of “American Dirt” was widely castigated for the way she depicted a Mexican mother and son struggling to cross the U.S. border. As the British novelist Zadie Smith observed in 2019, “The old — and never especially helpful — adage ‘write what you know’ has morphed into something more like a threat: ‘Stay in your lane.’”

[ . . . ]

[I]n 2022 my agents’ foreboding was realized. The manuscript of “Trial” was rejected by roughly 20 imprints of major New York publishers. A number of them found it impressive; several opined that it evoked my best work. Nonetheless, my ethnicity was now deeply problematic.

One publisher said she only cared to hear on such subjects from “marginalized voices.”

[ . . . ]

Not once did anyone suggest that any aspect of the manuscript was racially insensitive or obtuse. Rather, the seemingly dominant sentiment was that only those personally subject to discrimination could be safely allowed to depict it through fictional characters. Luckily, I found an independent publisher [Post Hill Press] prepared to brave the new dispensation.

Six questions to consider:

- If racial identity is determinative (or largely so), does the same hold true when it comes to gender, religion, economic status, and national identity? Can men write about women? Can straights write about trans people? Can Catholics write about the Holocaust?

- What do we know about the identity of those making identity decisions? Are they people of color, gay, Hispanic, young, old, or white? Should white editors be able to cancel a book on racial identity grounds without consulting people of color?

- “Should empathy and imagination be allowed to cross the lines of racial identity?” asks Patterson. “This goes to the heart of what kind of literature we want, and what kind of society we aspire to be.”

- Let us assume that the outcome would be different if Patterson’s “Trial” had been authored by a person of color, which would ostensibly serve the value of more diversity and inclusiveness in publishing. Even if one were to grant that, should that nonetheless mean that racial identity considerations should cancel the Patterson authors of the world?

- Even if one were to grant, if only for the sake of argument, that Patterson’s book lacked literary merit, how much weight should author-identity issues be given when it comes to publishing decisions?

- Moreover, if a work is of some considerable merit to an afflicted class, should that work be denied publication because the author is not a member of that class?

Lastly (presented without comment):

Related

- Jackie K. Cooper, “Our Interview with Author Richard North Patterson,” YouTube (June)

- Pamela Paul, “The Long Shadow of ‘American Dirt’,” The New York Times (Jan. 26)

- Laura Miller, “So Why Did Big New York Publishers Reject Richard North Patterson’s New Novel? Is it because he’s white? Or because it’s not very good?,” Slate (June 20) (re: this article, see question # 5 above).

Trump raises 1-A defense in Georgia voting fraud case

- David Wickert, “Trump plans First Amendment defense to Fulton criminal charges,” Atlanta-Journal Constitution (Nov. 27)

Donald Trump will defend himself against charges that he illegally sought to overturn the 2020 election in Georgia by arguing his claims about voting fraud were “core political speech” protected by the First Amendment.

In a filing on Monday in Fulton County Superior Court, Trump attorney Steven Sadow said the former president will challenge his indictment on racketeering, conspiracy and other charges by asserting his right to political speech and expressive conduct.

[ . . . ]

Judge Scott McAfee has already dismissed First Amendment challenges from two other defendants — attorneys Kenneth Chesebro and Sidney Powell (both of whom later pleaded guilty). The judge cited numerous court cases in ruling that he must first establish a factual record before considering such challenges. McAfee said those facts must be established at trial.

In Monday’s court filing, Sadow argued the judge can consider a pre-trial First Amendment challenge if the facts laid out in the indictment are not disputed by the defendants. To pursue such a defense, Trump presumably would have to acknowledge his voting fraud claims were false.

“Here, the indictment’s recitation of supposedly ‘false’ statements and facts, undisputed solely for purposes of a First Amendment-based general demurrer/motion to dismiss, show that the prosecution of President Trump is premised on content-based core political speech and expressive conduct protected by the First Amendment,” Sadow argued.

Cert. petition: Can the government ban politically expressive car honking?

The case is Porter v. Martinez. The two issues raised in the case are (1) whether the government may categorically ban expressive conduct, such as expressive honking of car horns, in the name of traffic safety without presenting any evidence that its ban furthers that interest, and (2) whether the government may categorically ban expressive conduct, such as expressive honking of car horns, where the government had not tried — or at least seriously considered — using less restrictive measures to address its traffic safety concerns.

From Petitioner’s cert. petition

Statement of Facts: In October 2017, Susan Porter honked her car horn multiple times when passing a roadside protest occurring outside of a U.S. Congressman’s office in Vista, California. Pet. App. 138a–140a. A San Diego County Sheriff’s Deputy cited Porter for violating Section 27001. Pet. App. 139a–140a. When the Sheriff’s Deputy failed to appear at Porter’s hearing to contest the citation, the citation was dismissed.

Thereafter, Porter filed suit alleging that [CAL. VEH. CODE] Section 27001 violates the First Amendment as applied to protected expression, namely expressive honking. The district court granted summary judgment for the Government. A panel of the Ninth Circuit affirmed over a dissent by Judge Berzon. The Ninth Circuit recognized that a car horn can constitute expressive conduct and that, as a result, Section 27001 could be understood to “prohibit[] some expressive conduct” protected by the First Amendment. Pet. App. 19a–21a (“The parties also do not dispute that at least some of the honking prohibited by Section 27001 is expressive for First Amendment purposes. We agree.”). Nonetheless, the court held the law was constitutional. In holding that Section 27001 passed intermediate scrutiny, the Ninth Circuit held that the law “further[ed] an important or substantial governmental interest,” “unrelated to the suppression of free expression” — namely traffic safety.

[. . .]

Ninth Circuit ruling: Since the dawn of the automobile at the turn of the twentieth century, Americans of all political persuasions have honked their cars’ horns to express their support or displeasure and add their voice to the political and civic dialogue of this country. Every day across this country, motorists use their vehicles’ horns to express themselves when passing roadside picket lines, demonstrations, and protests. Such “honks” not only operate as means for the motorist to communicate their support to their fellow citizens but also to amplify their fellow citizens’ cause. The car horn is the sound of democracy in action.

Petitioner Susan Porter comes before this Court because the Ninth Circuit wrongly upheld California’s categorical ban on expressive car horn honking, under which she was issued an infraction for honking her horn in support of a roadside political protest. California’s Vehicle Code prohibits the use of a car horn for purposes other than ensuring the safe operation of a vehicle (herein referred to as “non-warning honking”). See CAL. VEH. CODE § 27001. The Government primarily justified its law by reference to its interest in traffic safety. However, the Government admitted that it knows of not one accident caused or threatened by non-warning honking.

Dissent in Ninth Circuit: BERZON, Circuit Judge, dissenting:

The majority today upholds a ban on a popular form of political expressive conduct — honking horns to support protests or rallies. Political protest “has always rested on the highest rung of the hierarchy of First Amendment values.” Carey v. Brown, 447 U.S. 455, 467 (1980). Defendants’ enforcement of California Vehicle Code Section 27001 prohibited Susan Porter from exercising her right to participate in political protest by honking in support of a demonstration against an elected official.1 Yet, there is no evidence in the record (or elsewhere, as far as I can determine) that such political expressive horn use jeopardizes traffic safety or frustrates noise control. I therefore respectfully dissent. I would hold that Section 27001 does not withstand intermediate scrutiny insofar as it prohibits core expressive conduct, and is therefore unconstitutional in that respect.

[ . . . ]

Turning now to the merits of Porter’s First Amendment challenge, I would hold that Section 27001 is unconstitutional as applied to political expressive conduct such as Porter’s. The majority’s fundamental error, in my view, in concluding otherwise is that it does not sufficiently focus on the specific type of enforcement at the core of this case — enforcement against honking in response to a political protest.

Generally, when a statute has both constitutional and unconstitutional applications, we “enjoin only the unconstitutional applications . . . while leaving other applications in force.” Ayotte v. Planned Parenthood of N. New England, 546 U.S. 320, 329 (2006). Porter was cited for honking in support of a political protest, and she asserted in her deposition that the threat of enforcement has chilled her future plans only for such political honking; she did not aver an intent to engage in any other honking she characterizes as “expressive.”

So the particular “subset of the statute’s applications” cognizably challenged here is the enforcement of Section 27001 against political protest honking. Hoye v. City of Oakland, 653 F.3d 835, 857 (9th Cir. 2011). The requested relief in Porter’s complaint does include enjoining Defendants from enforcing Section 27001 against “protected speech or expression.”

The complaint and her briefs on appeal assert that “expressive” honking can include using a vehicle horn to “express support or approval of parades, protests, rallies, demonstrations, or fundraising or for other expressive purposes such as greeting a relative, friend, or acquaintance.” Relying on this expansion of the requested relief beyond Porter’s own past experience and desired future actions, the majority states that, because Porter seeks to enjoin enforcement against all expressive honking, “we decide only whether the statute is unconstitutional on its face or as applied to all expressive honking.”

Hat tip to David Keating for alerting me to this case.

‘Unchecked spread of anti-Semitism’ lawsuit at UC Berkeley Law School

- Bob Egelko, “Lawsuit accuses UC Berkeley Law School of ‘Unchecked spread of anti-Semitism’,” San Francisco Chronicle (Nov. 28)

A Zionist organization sued the University of California on Tuesday, accusing the UC Berkeley Law School of promoting anti-Semitism and discriminating against Jews by allowing student groups to bar Zionists as speakers at their meetings.

“Zionism is an integral component of Jewish identity,” attorneys for the Louis D. Brandeis Foundation said in a lawsuit filed in federal court in San Francisco. “Anti-Zionism is discrimination against those who recognize the Jews’ ancestral heritage — in particular the Jews’ historic connection to the land of Israel.”

The suit says it “targets the longstanding, unchecked spread of antisemitism at the University of California Berkeley.”

They cited a policy announced in August 2022 by Law Students for Justice in Palestine and now followed, according to the suit, by 23 of the 100 organizations in the 1,100-student law school. Saying Zionism is used to justify the displacement and oppression of Palestinians, the groups have adopted bylaws saying they would not invite pro-Zionist speakers, who describe Israel as a Jewish state.

FIRE weighs in on X Corp.’s lawsuit against Media Matters

- “FIRE Statement: X Corp's lawsuit and Texas's investigation into Media Matters for America are deeply misguided,” FIRE (Nov. 21)

X’s lawsuit against Media Matters for America, a media watchdog non-profit, complains about the “impression” a recent Media Matters report conveyed about X’s advertisers and user experience. But opinionated criticism is protected by the First Amendment.

If X believes Media Matters’ report is unfair, it is free to make its case in the court of public opinion. Instead, X has chosen to use the legal process as a means of imposing a financial cost on a critic.

X’s suit is a classic example of a SLAPP — a strategic lawsuit against public participation — and another demonstration of Elon Musk’s fair-weather friendship with free expression. And because it was filed in a north Texas jurisdiction with no substantial relationship to the parties or the case, it illustrates the need for a federal anti-SLAPP statute.

The Texas Attorney General’s initiation of an investigation into Media Matters’ protected expression is equally troubling. Ostensibly launched to protect the public against being “deceived,” the Attorney General’s investigation springs from the dubious rationale that law enforcement, not the public, is best equipped to decide what’s true and what isn’t. That’s a deeply misguided presumption — and this investigation will result in the exact chilling effect on free speech it claims to deter.

Related

- Benjamin Edwards, “Musk’s Media Matters misstep,” The Hill (Nov. 23)

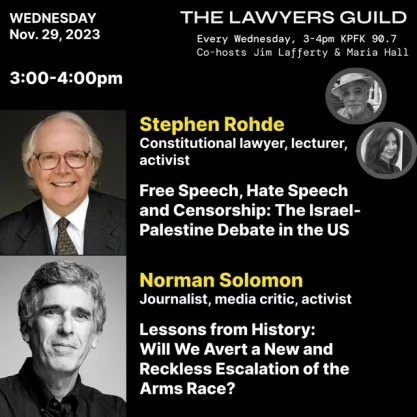

Radio event: Rhode and Solomon on censorship and the Israel-Palestine conflict

On Nov. 29th, from 3-4 pm PST on KPFK 90.7 FM, there will be a program with Constitutional law expert Stephen Rohde on the topics of free speech, hate speech, and censorship surrounding the Israel-Palestine debate in the US.

Journalist, media critic, and author Norman Solomon will join to discuss how a new and reckless escalation of the arms race might be averted. Co-hosts: Jim Lafferty and Maria Hall.

Decline in local news outlets continues

- David Bauder, “Decline in local news outlets accelerates despite efforts to help,” Free Speech Center (Nov. 21)

The decline of local news in the United States is speeding up despite attention paid to the issue, to the point where the nation has lost a third of its newspapers and two-thirds of its newspaper journalists since 2005.

An average of 2.5 newspapers closed each week in 2023 compared with two a week the previous year, in a reflection of an ever-worsening advertising climate, according to a Northwestern University study issued Nov. 16. Most are weekly publications, in areas with few or no other sources for news.

“My concern is that the acceleration that we’re seeing is only going to worsen,” said Tim Franklin, who heads the local news initiative at Northwestern’s Medill journalism school.

At its current pace, the country will hit 3,000 newspapers closed in two decades sometime next year, with just under 6,000 remaining, the report said. At the same time, 43,000 newspaper journalists lost their jobs, most of them at daily publications, with the advertising market collapsing.

Related

- “Perilous times: The plight of local papers,” FAN 401 (Nov. 15)

Forthcoming book: Turley on free speech

- Jonathan Turley, “The Indispensable Right: Free Speech in an Age of Rage,” Simon & Schuster (June 18, 2024)

A timely, revelatory look at freedom of speech — our most basic right and the one that protects all the others.

Free speech is a human right, and the free expression of thought is at the very essence of being human. The United States was founded on this premise, and the First Amendment remains the single greatest constitutional commitment to the right of free expression in history. Yet there is a systemic effort to bar opposing viewpoints on subjects ranging from racial discrimination to police abuse, from climate change to gender equity. These measures are reinforced by the public’s anger and rage; flash mobs appear today with the slightest provocation. We all lash out against anyone or anything that stands against our preferred certainty.

The Indispensable Right places the current attacks on free speech in their proper historical, legal, and political context. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights were not only written for times like these, but in a time like this. This country was born in an age of rage and for 250 years we have periodically lost sight of the value of free expression. The history of the struggle for free speech is the story of extraordinary people—nonconformists who refuse to yield to abusive authority — and here is a mosaic of vivid characters and controversies.

Jonathan Turley takes you through the figures and failures that have shaped us and then shows the unique dangers of our current moment. The alliance of academic, media, and corporate interests with the government’s traditional wish to control speech has put us on an almost irresistible path toward censorship. The Indispensable Right reminds us that we remain a nation grappling with the implications of free expression and with the limits of our tolerance for the speech of others. For rather than a political crisis, this is a crisis of faith.

New article on free speech: On ‘quasi-state agents’

- Erin Miller, “Quasi-State Agents in First Amendment Doctrine,” SSRN (Nov. 16)

This article challenges the orthodoxy that First Amendment speech rights can bind only the state. I argue that the primary justification for the freedom of speech is to protect fundamental interests like autonomy, democracy, and knowledge from the kind of extraordinary power over speech available to the state. If so, this justification applies with nearly equal force to any private agents with power over speech rivaling that of the state. Such a class of private agents, which I call quasi-state agents, turns out to be a live possibility once we recognize that state power is more limited than it seems and can be broken down into multiple, equally threatening parts.

Quasi-state agents might include a limited set of corporations, from the largest social media platforms to powerful private employers. However, because quasi-state agents are not exactly like state agents, but pursue important private aims that the state cannot, I argue that the First Amendment might bind them slightly differently (and less demandingly) than it does the state. Drawing on examples from American state and comparative constitutional law, I offer several analytical models for understanding this differential application.”

More in the news

- “Sandy Hook Families Offer To Settle Alex Jones’ Legal Debt For a Minimum of $85 Million,” First Amendment Watch (Nov. 28)

- Lynn Greenky, “Supreme Court to consider giving First Amendment protections to social media post,” The Conversation (Nov. 27)

- Eugene Volokh, “USC Professor Put on Remote Teaching After Saying Hamas Should Be Killed,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Nov. 27)

- “Annapolis ‘First Amendment Auditor’ Convicted for Criminal Trespassing at Calvert Health Department,” NewsNet (Nov. 27)

- “Political Speech Federal Court Allows Ethics Probe Into North Carolina Justice’s Comments to Continue,” First Amendment Watch (Nov. 27)

- Eugene Volokh, “Challenge to NYU Law Review's Race and Sex Preferences May Proceed Pseudonymously, at Least for Now,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Nov. 22)

- Hillel Italie, “Salman Rushdie receives first-ever Lifetime Disturbing the Peace Award,” Free Speech Center (Nov. 22)

- “Florida Faces a Second Lawsuit Over Its Effort To Disband Pro-Palestinian Student Groups,” First Amendment Watch (Nov. 21)

- Jessica Levinson, “Trump is about to learn the truth about the First Amendment,” MSNBC (Nov. 21)

- “Radio reporter arrested during protest to receive $700,000 settlement from Los Angeles County,” Free Speech Center (Nov. 20)

2022-2023 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Review granted

Vidal v. Elster (argued Nov. 1)

O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier (argued Oct. 31)

Moody v. NetChoice, LLC / NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton / NetChoice, LLC v. Moody

National Rifle Association of America v. Vullo

Pending petitions

Pierre v. Attorney Grievance Commission of Maryland

Sharpe v. Winterville Police Dept.

Winterville Police Department v. Sharpe

Jarrett v. Service Employees International Union Local 503, et al

Porter v. Board of Trustees of North Carolina State University

Alaska v. Alaska State Employees Association

Tingley v. Ferguson (distributed for conference 7 times as of Nov. 28)

State action

Lindke v. Freed (argued Oct. 31) Review denied

Stein v. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Inc., et al.

Blankenship v. NBCUniversal, LLC

Center for Medical Progress v. National Abortion Federation

Free speech related

Miller v. USA (pending) (statutory interpretation of 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c) advocacy, lobbying and protest in connection with congressional proceedings)

Previous FAN

FAN 401: “Perilous times: The plight of local papers”

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE or of Mr. Collins.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

VICTORY: Jury finds Tennessee high school student’s suspension for sharing memes violated the First Amendment

DOJ must not investigate elected officials for criticizing immigration enforcement

FIRE statement on calls to ban X in EU, UK