Table of Contents

Was John Milton naïve? Is counterspeech a real remedy or a First Amendment fantasy? — First Amendment News 397

First Amendment News is a weekly blog and newsletter about free expression issues by Ronald K. L. Collins. It is editorially independent from FIRE.

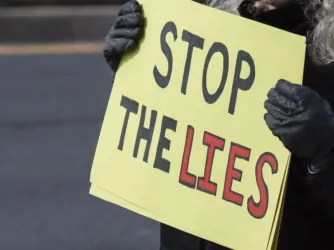

It seems that almost nothing (save gravity and death) can pass as truth today. No lie is fully beyond the pale (consider Trump’s or Menendez’s whoppers), and virtually no falsehood is beyond dispute (with the exception of those aired in the Dominion defamation cases), and nothing is certain: “Who you gonna believe, me or your lying eyes?” is how Chico Marx once put it in comic parlance.

We live by lies. They make life possible, pleasurable, and profitable. What would life be if shackled to truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth?

Consider Symposium: “Noble Lies and the First Amendment,” University of Cincinnati Law Review (1996), and Collins and Skover, “Afterword: New ‘Truths’ and the Old First Amendment,” University of Cincinnati Law Review (1996).

Are lies adequately countered by truth? Perhaps. Or they might as well be solidified by yet other lies. Do you ever tire of the “lie” that truth can be an effective counter to falsehood? Or, at the very least, do you ever pause when someone champions that ideal as an effective way to respond to the worst kinds of harmful speech? Just asking, mind you!

In defense of pure pandemonium

Who can read the following poetic words and not want to pledge instant fidelity to the free speech principle?

[T]hough all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously, by licensing and prohibiting, to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter?

So wrote John Milton in his 1644 tract “Areopagitica.” If Milton the poet was a friend of the Enlightenment, then Milton the polemicist was also an enemy of the Church and its rule over the lives of its subjects. If he helped advance the cause of truth in the marketplace, his libertarian side made it possible for any truth to be fiercely and falsely attacked. If his notion of a free press pointed to its use in furtherance of the rule of law, the radical in him defended the killing of the king. And if high values took refuge in his thought, low ones (such as his defense of polygamy) found sanctuary in his writing. Little wonder, then, that he coined the word “pandemonium.” This chaos — the good, the bad, the blessed, and the profane, all warring — was intensified by print, the medium Milton championed with poetic passion.

Truth prevailing over falsehood. Really? If only Milton were alive to witness the duplicitous politics of our times, when truth dies daily on the altar of the medium of the moment.

Combat, competition, and counterspeech in the marketplace

Though he was skeptical of the idea of certainty in almost any form, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (the old Civil War veteran) was charmed by military conflict and capitalist competition. “The ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.”

Yes, that was Holmes dissenting in Abrams v. United States in 1919. In his 1925 dissent in Gitlow v. New York he warned us that his free speech experiment could go south. “If . . . dictatorship[s] are destined to be accepted by the dominant forces of the community,” he wrote, “the only meaning of free speech is that they should be given their chance and have their way.”

Of course, he was fine with that. “Let it be,” is how he might have replied.

And then there was Justice Louis Brandeis, the great progressive and champion of counterspeech in American jurisprudence. “If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education,” he wrote in his 1927 concurrence for Whitney v. California, “the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.”

When one reads Brandeis’ words carefully, one can appreciate how he qualified his position:

- There must be “time” to “expose” falsehoods

- Such falsehoods should be revealed through “discussion”

- “Education” is the corrective process, not indoctrination or misrepresentation.

If all of those conditions are satisfied, only then is “more speech” the answer. Absent the requisite time and the ability to expose lies, and the opportunity to do so by discussion in the service of education, counterspeech is of no Brandeisian value.

Remedy or fantasy?

Milton’s optimistic Enlightenment ideal buttressed by Holmes’s cynical marketplace model and then liberated by Brandeis’ counterspeech theory together form a key tenet of our modern notion of First Amendment freedom.

Time and again, in court opinions or public pronouncements, counterspeech is hailed as the answer to hate speech, politically false speech, or scientifically indefensible speech. All of this should prompt realists to reexamine the idea that counterspeech is indeed an effective response to falsity in the competition for public approval in the modern arenas of communication.

Among other things, for counterspeech to be truly effective there must be a certain degree of open-mindedness combined with a willingness to be patient as the other side makes its case. To the same effect, it also presumes a certain willingness to admit error and that previous views must yield to those of others.

When one pauses to consider all of the relevant qualifiers and needed verifications, counterspeech may prove to be more of a poker card to be played than a bona fide argument to be made.

Nota bene:

Mind you, I am not saying that the counterspeech argument has no place in First Amendment jurisprudence. Rather, my point is simply that its role seems overrated in ways that tend to give the impression that counter-speech actually diminishes the dangers of certain harmful speech. To be sure, there are other reasons why speech should be protected, even if the counterspeech proves to be, well, rather useless.

Related

- G.S. Hans, “Changing Counterspeech,” Cleveland State Law Review (2021)

SCOTUS to hear social media cases

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier

- Moody v. NetChoice, LLC / NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton / NetChoice, LLC v. Moody

Related

- Caroline Mimbs Nyce, “The Supreme Court Cases That Could Redefine the Internet,” The Atlantic (Sept. 30)

In the aftermath of the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, both Facebook and Twitter decided to suspend lame-duck President Donald Trump from their platforms. He had encouraged violence, the sites reasoned; the megaphone was taken away, albeit temporarily. To many Americans horrified by the attack, the decisions were a relief. But for some conservatives, it marked an escalation in a different kind of assault: It was, to them, a clear sign of Big Tech’s anti-conservative bias.

That same year, Florida and Texas passed bills to restrict social-media platforms’ ability to take down certain kinds of content. (Each is described in this congressional briefing.) In particular, they intend to make political “deplatforming” illegal, a move that would have ostensibly prevented the removal of Trump from Facebook and Twitter. The constitutionality of these laws has since been challenged in lawsuits—the tech platforms maintain that they have a First Amendment right to moderate content posted by their users. As the separate cases wound their way through the court system, federal judges (all of whom were nominated by Republican presidents) were divided on the laws’ legality. And now they’re going to the Supreme Court.

On Friday, the Court announced it would be putting these cases on its docket. The resulting decisions could be profound: “This would be—I think this is without exaggeration—the most important Supreme Court case ever when it comes to the internet,” Alan Rozenshtein, a law professor at the University of Minnesota and a senior editor at Lawfare, told me. At stake are tricky questions about how the First Amendment should apply in an age of giant, powerful social-media platforms. Right now, these platforms have the right to moderate the posts that appear on them; they can, for instance, ban someone for hate speech at their own discretion. Restricting their ability to pull down posts would cause, as Rozenshtein put it, “a mess.” The decisions could reshape online expression as we currently know it.”

Additional articles

- “The Supreme Court Will Decide Whether State Laws Limiting Social Media Platforms Violate the Constitution,” First Amendment Watch (Sept. 29)

- Mark Sherman, “Supreme Court to decide if state laws limiting social media platforms violate Constitution,” Free Speech Center (Sept. 29)

- Ilya Somin, “Supreme Court Will Consider Cases Challenging Florida and Texas Social Media Laws,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Sept. 29)

Straub on dangers of attempting to regulate AI

- Jeremy Straub, “Blumenthal, Hawley AI framework could damage AI industry, violate First Amendment,” The Hill (Oct. 1)

As our nation grapples with the fast-paced evolution of artificial intelligence (AI), it is crucial to strike the right balance between preventing AI’s potential risks and fostering innovation. Sens. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) and Hawley’s (R-Mo.) bipartisan AI framework, despite its laudable intentions—such as protecting children and promoting transparency—threatens to stifle AI innovation by regulating AI development instead of just use. In doing so, it may even infringe upon our First Amendment rights.

Regulating development is a bad idea. AI development must be treated as protected speech and is subject to the same prohibition on prior restraint as any other speech form. Writing software as code is not meaningfully different, as a form of expression, than writing it in a narrative form. Various AI-powered systems have been developed that convert text descriptions into functional software, demonstrating the similarity between these two forms of expression. Regulating the development of AI poses a significant challenge by regulating the use of software-descriptive language. It will also be difficult for regulators to differentiate between AI and other types of software.

Jeremy Straub is the director of the North Dakota State University Cybersecurity Institute, a Challey Institute senior faculty fellow, and an associate professor in the NDSU Department of Computer Science

Dominion employee defamation suit against OAN settled

- Tierney Sneed and Marshall Cohen, “Far-right network OAN settles 2020 election defamation suit brought by ex-Dominion executive,” CNN Business (Sept. 5, 2023)

Far-right TV network One America News and one of its on-air personalities settled a defamation lawsuit brought by a former executive at Dominion Voting Systems, the election technology company that was falsely accused of rigging the 2020 election, according to new court filings.

Dominion’s former top security official Eric Coomer sued OAN and its correspondent Chanel Rion in the wake of the 2020 election, when they repeatedly peddled unfounded claims that he and Dominion were involved in massive election fraud in 2020 by flipping millions of votes from Donald Trump to Joe Biden.

Terms of the out-of-court settlement, which was made public in a court filing, weren’t immediately available. The filing said OAN and Rion “have fully and finally settled the disputes” with Coomer, but did not provide any other details. Court records indicate that the deal was brokered late last week.

Conservation officer sued for criticizing wealthy ranch owner’s airstrip permit

- “FIRE defends Idaho conservation officer sued for criticizing wealthy ranch owner’s airstrip permit,” FIRE (Oct. 2)

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression is defending a lifelong Idaho conservation officer at the Idaho Supreme Court after he was sued by a wealthy tech magnate for nothing more than exercising his First Amendment rights.

Gary Gadwa is a former emergency medical technician with 38 years of experience in search-and-rescue operations in the federally protected Sawtooth National Recreation Area. Even in retirement, he volunteers as a fire lookout, spending weeks at a time in the mountains looking for the telltale signs of forest fires at Salmon–Challis National Forest.

“I’ve dedicated my life to two things: protecting my community and protecting the Sawtooth Mountains,” said Gary. “I’ll never stop speaking my mind, no matter who tries to silence me.”

In 2021, Michael Boren, co-founder of Boise-based financial tech firm Clearwater Analytics, applied for a county permit to designate part of his Stanley, Idaho, ranch as an airstrip. When Boren claimed it could be used for search-and-rescue operations, Gary felt the need to speak up and speak out. Drawing on his experience, Gary contributed to an op-ed and testified before a county commission that he believed the airstrip would not serve future rescue operations and could have a negative effect on local wildlife and the natural beauty of the Sawtooth Mountains.

Boren was ultimately granted the permit over Gary’s and many others’ objections. But instead of taking his permit and going home, Boren turned around and sued Gary and more than 20 other critics for defamation.

“Gary spoke up when he saw something he thought would harm his community, just like every American should,” said FIRE senior attorney JT Morris. “Speech on public issues lies at the heart of the First Amendment — and the First Amendment squarely protects Gary’s speech opposing a designated airstrip that neighbors public lands.”

Texas drag ban law struck down

- Susanna Granieri, “Texas Drag Ban Declared Unconstitutional, Permanently Enjoined by Federal Judge,” First Amendment Watch (Sept. 28)

A federal judge in Texas permanently enjoined the state’s law restricting public drag performances on Tuesday, declaring it an unconstitutional infringement on freedom of expression.

“Not all people will like or condone certain performances,” wrote U.S. District Judge David Hittner of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas. “This is no different than a person’s opinion on certain comedy or genres of music, but that alone does not strip First Amendment protection.”

The law, SB 12, which was supposed to go into effect on Sept. 1, sought to ban “sexually oriented performances” in public places, describing such performances as those that display sexual conduct like “the exhibition of sexual gesticulations using accessories or prosthetics that exaggerate male or female sexual characteristics.”

The ban would have applied to performances “on public property at a time, in a place, and in a manner that could reasonably be expected be viewed by a child,” and anyone who controlled a commercial enterprise allowing “sexually oriented performance to be presented on the premises in the presence of” a minor would have been subject to thousands of dollars in fines.

Judge Hittner ruled that the law is “unconstitutionally vague.” He also wrote that it was “overbroad,” meaning that its language regulates both protected and unprotected speech. It “impermissibly infringes on the First Amendment and chills free speech,” Hittner wrote, and a “large amount of constitutionally-protected conduct can and will be wrapped up in the enforcement of SB 12.”

SCOTUS denies review in Eastman emails case

- Josh Gerstein and Kyle Cheney, “Supreme Court rejects Eastman’s bid to scrap rulings that sent his emails to Jan. 6 investigators,” Politico (Oct. 2)

The Supreme Court, minus a recused Clarence Thomas, has turned down a bid by attorney John Eastman to erase court rulings that described him as a linchpin in former President Donald Trump’s bid to subvert the 2020 election.

The high court’s decision Monday essentially enshrines rulings by a federal district judge in California that found Eastman’s emails contained evidence of a likely crime related to Trump’s efforts.

[ . . . ]

Eastman’s effort to wipe out unfavorable court rulings took on added significance after a Georgia grand jury indicted him in August alongside Trump and 17 other co-defendants, alleging a sweeping effort to subvert the state’s election results in 2020. California bar authorities are also seeking to strip Eastman’s law license for his efforts, and a trial on the matter has been underway since June.

Take note!

- Nico Perrino, “What happens when America’s future leaders reject the liberty on which it was founded?” FIRE (Oct. 2)

Sadly, support for mob censorship tactics is growing among college students nationwide. Forty-five percent said blocking other students from attending a speech may be acceptable in some situations. A whopping 27% said the same about using violence to stop a campus speech. That’s up from 37% and 20%, respectively, in the previous year.

Lukianoff on the new Red Scare on college campuses

- Greg Lukianoff, “The new Red Scare taking over America's college campuses,” Washington Examiner (Sept. 25)

In my [forthcoming] book with journalist Rikki Schlott, “The Canceling of the American Mind,” we show that campus cancel culture is not just real, it’s on a historic scale. We define “cancel culture” as the uptick around 2014 of campaigns to get people fired, expelled, deplatformed, or otherwise punished for speech that is (or would be) protected by the First Amendment and the climate of conformity that results.

The statistics show that we are going to be studying this period of repression 50 to 100 years from now, just like we study the Red Scare.

In the last nine and a half years, we know of more than 1,000 campaigns to get professors punished for their free speech or academic freedom. Of those, about two-thirds succeeded in getting the professor punished, and almost 200 of them, nearly twice the number estimated for the Red Scare, ended up with the professor getting fired.

[ . . . ]

We also know that 1,000 is a wild underestimate, as about 1 in 6 professors report having been disciplined or threatened with discipline for their speech, and a whopping 1 in 3 reported having been pressured by colleagues to avoid researching controversial topics.

Related

- National First Amendment Summit panel: “The First Amendment on Campus and Online,” Jeannie Suk Gersen, Will Creeley, and Nadine Strossen, and Jeffrey Rosen (Sept. 18)

Forthcoming scholarly article on 303 Creative and public accommodation laws

- Michael L. Smith, “Public Accommodations Laws, Free Speech Challenges, and Limiting Principles in the Wake of 303 Creative,” Louisiana Law Review (Forthcoming, 2023)

In 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, the Supreme Court ruled that Colorado’s Anti-Discrimination Act’s prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation violated the First Amendment rights of Lorie Smith, a website designer who refused to make wedding websites for same-sex couples. This Article argues that the Court’s ruling rested on a vision of state control over speech that was divorced from the law before it. Using this framing of the law to conjure up inapplicable hypothetical scenarios of state-mandated expression, the Court found in Smith’s favor. And yet, in responding to the dissent’s concerns that the Court’s logic could be employed to justify discrimination in a host of additional circumstances, such as interracial marriages, the Court dodged, asserting that those weren’t the facts before the Court.

I parse out the errors in the Court’s reasoning and demonstrate why its assurances of a limited holding are groundless. The logic the Court employs in 303 Creative may extend to a host of cases, including interracial marriages, any case in which a business argues that its goods or services are expressive, and, potentially, to cases involving free exercise claims by individuals and businesses seeking to discriminate on religious grounds.

In the face of these potential consequences, I propose two strategies for limiting 303 Creative’s impact. The first proposes a more restrictive approach to First Amendment claims when businesses seek to discriminate against members of suspect classes identified in the Court’s Equal Protection jurisprudence. But this approach carries a risk of stagnation in a nation of diverse prejudices, as the Court has proven loathe to identify new suspect classes. This leads to an alternate approach.Drawing on Jamal Greene’s scholarship, I propose that courts engage in proportional analysis of competing rights claims. Rather than the standard approach of maximizing the rights claims of one side of a dispute and minimizing other’s, courts should weigh the interests of each against each other. Doing so may rein in the absolutist and overly abstract reasoning on display in the Court’s 303 Creative opinion, and encourage more measured and realistic discussion of rights in future cases.

Podcast: Lakier on government ‘jawboning’ of platforms

- “Stanford Legal” podcast: Evelyn Douek, “Government Platform Communication, Jawboning, and the First Amendment,” Stanford Law School (July 10)

On July 4, a district court issued an injunction prohibiting large swathes of the government from communicating with platforms about content moderation in almost any way. Evelyn Douek sits down with Genevieve Lakier, Professor of Law at the University of Chicago Law School, to talk about the opinion, the issue of government “jawboning” of platforms, and how the First Amendment has, should and shouldn’t think about this problem.

YouTube — Looking back: Amar on First Amendment history

- “So to Speak” podcast: Akhil Amar, “First Amendment history with Yale Professor Akhil Amar,” FIRE (Sept. 30, 2021)

More in the news

- Mike Schneider, “Disney, DeSantis legal fights ratchet up as company demands documents from Fla. governor,” Free Speech Center (Oct. 2)

- Josh Blackmun, “The 12th Annual Harlan Institute-Ashbrook Virtual Supreme Court,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Oct. 2) (“Teams of two HS students will write a brief and present oral arguments on Moody v. NetChoice.”)

- James Taranto and David B. Rivkin, Jr., “Justice Alito’s First Amendment,” Wall Street Journal (Oct. 1)

- Susanna Granieri, “Judge Restricts Sharing of Information About Jurors in Trump’s Upcoming Trial,” First Amendment Watch (Sept. 27)

- Miles Klee, “Twitter Fires Election Integrity Team Ahead of 2024 Elections,” Rolling Stone (Sept. 27)

2023-2024 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Review granted

Pending petitions

- Alaska v. Alaska State Employees Association

- Speech First, Inc. v. Sands

- Gonzalez v. Trevino

- Stein v. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Inc., et al.

- O’Handley v. Weber

- Mazo v. Way

- National Rifle Association of America v. Vullo

- Tingley v. Ferguson

- Frese v. Formella

State action

- Lindke v. Freed (to be argued Oct. 31)

Review denied

Previous FAN

FAN 396: “X-man, champion of free speech? How absurd!”

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE or of Mr. Collins.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

The American people fact-checked their government

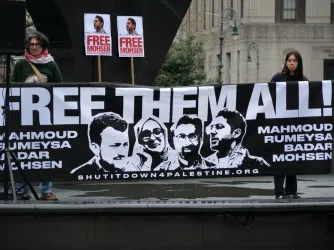

Facing mass protests, Iran relies on familiar tools of state violence and internet blackouts

Unsealed records reveal officials targeted Khalil, Ozturk, Mahdawi solely for protected speech