Table of Contents

What’s wrong with First Amendment casebooks? Where to begin? First Amendment News 399

First Amendment News is a weekly blog and newsletter about free expression issues by Ronald K. L. Collins. It is editorially independent from FIRE.

If I had to write a First Amendment casebook for law schools (and I almost did), I certainly would not model it after any of the main ones now in use. Though most are expensive (some cost upwards of $300), that is certainly not their major flaw.

My problem with these tomes is that they are first and finally about doctrinal law announced by the Supreme Court (and even on that score they can be inadequate), and feature very little about the modern practices of law in trial and appellate courts.

Don’t get me wrong, I have no truck with the Marbury v. Madison (1803) principle of the supremacy of Supreme Court review. My problem is there is much more to First Amendment law than high court case-crunching. Below are seven reasons, among others, why I think most First Amendment casebooks are inadequate in preparing law students to practice in this area of law, which is expanding.

- A Supreme Court-centric approach (SCA) ignores several important and timely areas of free speech law. For example, contemporary campus speech controversies. While all the casebooks cover the student speech cases from Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School Dist. (1969) to Mahanoy Area School Dist. v. B.L. (2021), those cases hardly provide an informative understanding of what is going on in college campus censorship cases. Board of Education v. Pico (1982) notwithstanding, much, or even more of the same holds true when it comes to bans on — and challenges to — books used in public libraries and schools.

- SCA ignores important free speech protections not found in case law. For example, consider anti-SLAPP (strategic lawsuit against public participation) laws. It is amazing but true: Few, if any, First Amendment casebooks set aside room for explaining the importance of state anti-SLAPP laws — a vital weapon in the free speech arsenal.

- SCA ignores important free speech battles that occur outside of judicial settings. For example, consider the 2021 House impeachment resolution concerning then-President Trump’s Jan. 6 statements and whether they were protected under the First Amendment. Though the House and Senate hearings were momentous markers in our constitutional history, scant attention, if that, has been given to them in First Amendment casebooks.

- SCA often ignores the strategies used by lawyers to secure First Amendment victories including victories that are won without high court review. For example, none of the casebooks that I know of discuss the litigation strategies Laurence Tribe employed in the 11 free expression cases he argued in the Supreme Court. Or how much is revealed to students about the work of Floyd Abrams in shaping First Amendment law.

- SCA offers inadequate guidance on how to conceptualize modern developments in communications technologies. For example, consider how little help current Supreme Court doctrinal law is when it comes to facial recognition technologies of AI bots.

- Emphasis on select doctrines of First Amendment law ignores other less discussed but equally important tenets of that law. For example,the “of and concerning” requirement, which receives little attention in most casebooks despite its foundational importance in defamation law.

- When it comes to textualism and the speech and press clauses, SCA offers little meaningful guidance. For example, does AI algorithm-generated data amount to “speech” within the meaning of the First Amendment? Does the word “no” in the First Amendment actually mean no? What does the word “abridge” mean? Despite Justice Elena Kagan’s 2015 admonition that “we’re all textualists now,” today’s casebooks offer little evidence of that when it comes to the speech and press clauses.

Of course, the law of free expression expands well beyond Supreme Court precedents as evidenced by speech-and-press-enhancing laws in state constitutions, state statutes, and local laws. As every seasoned lawyer knows, the totality of such laws provides the truest measure of expressive liberty. And then there is the culture of free expression — simply consider how the advent of the internet effectively changed the law of obscenity in many (though not all) respects. Additionally, federal statutory protections are possible as evidenced by the proposed Freedom of Speech and Press Act.

Bottom lines

Has the time not come to slay these old doctrinal dragons? Or, to be more diplomatic: The time is long overdue to shelve these weighty (and pricey!) First Amendment casebooks. The present and future demand a new (perhaps electronic) generation of free-expression coursebooks.

Publishers take note, professors take action, and students get ready to move beyond yesterday and toward tomorrow.

Related

- Ronald Collins, “Litigation Scholarship” (June 11, 2013)

Note to reader: I will be out of the country for the next two weeks. But not to fear: We’ll be sharing two “Looking Back” issues of First Amendment News during that time — one featuring an interview with a well-known constitutional litigator, and the other being a profile of an unknown dissenter. Both are likely new to you.

See you on the other side of the calendar!

—RKLC

Gag order and Trump election interference case

- Rachel Weiner, Perry Stein, Tom Jackman, Devlin Barrett, and Spenser Hsu, “Trump placed under limited gag order in federal election case in D.C.,” The Washington Post (Oct. 16)

A federal judge issued a limited gag order Monday against Donald Trump, saying the former president must stop disparaging prosecutors, witnesses and court personnel involved in his upcoming D.C. trial on charges of conspiring to obstruct the results of the 2020 election.

The decision by U.S. District Judge Tanya S. Chutkan takes the country further into legally and politically uncharted territory with a criminal defendant who is known for incendiary public statements and is also a leading 2024 presidential candidate. “Mr. Trump is facing felony charges, and he does not get to respond to every criticism if that response could affect a potential witness,” Chutkan said in court. “He doesn’t get to use all the words.”

But the judge declined to impose restrictions as broad as the Justice Department wanted, saying Trump was free to verbally abuse President Biden, his likely rival in the 2024 election. Trump can also claim that the case against him is politically motivated, as long as he doesn’t denigrate individual prosecutors.

“Mr. Trump can certainly claim he’s being unfairly prosecuted, but I cannot imagine any other case where a defendant is allowed to call the prosecutor ‘deranged,’ or a ‘thug,’ and I will not permit it here simply because the defendant is running a political campaign,” Chutkan said, quoting from past Trump statements to make her point.

[ . . . ]

“Today’s decision is an absolute abomination and another partisan knife stuck in the heart of our Democracy by Crooked Joe Biden, who was granted the right to muzzle his political opponent,” the unsigned statement from the Trump campaign said. “President Trump will continue to fight for our Constitution, the American people’s right to support him, and to keep our country free of the chains of weaponized and targeted law enforcement.”

PETA prevails: SCOTUS denies review in ag-gag case

- “Supreme Court Rejects North Carolina’s Appeal in Ag-Gag Law Dispute,” First Amendment Watch (Oct. 16)

The Supreme Court on Monday rejected North Carolina’s appeal in a dispute with animal rights groups over a law aimed at preventing undercover employees at farms and other workplaces from taking documents or recording video.

The justices left in place a legal victory for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals in its challenge to the state law, which was enacted in 2015. PETA has said it had wanted to conduct an undercover investigation at testing laboratories at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill but feared prosecution under the “Property Protection Act.”

In a 2-1 decision, the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in February that the law could not be enforced against PETA — and likely others in similar situations — when its undercover work is being performed to conduct newsgathering activities.

City repeals panhandling law after First Amendment challenge

- Danny Nguyen, “Alexandria repeals panhandling law, citing First Amendment issues,” The Washington Post (Oct. 14)

The Alexandria city council unanimously voted to repeal some restrictions on panhandling Saturday that city officials said had violated the First Amendment. The council heard arguments Tuesday from the city attorney’s office and Alexandria police in favor of rescinding an ordinance that restricted aggressive panhandling, including soliciting money using methods that cause fear of injury. Saturday’s 7-0 vote came after a follow-up hearing.

The ordinance, enacted in 1994, also limited panhandling within 15 feet of ATMs, which ran afoul of a 2015 decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit. (The 4th Circuit covers Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina.) The court ruled that a Charlottesville law that prohibited people from soliciting cash near a mall violated the free speech rights of homeless panhandlers.

Related

- “Army veteran arrested for holding sign to raise awareness of homeless vets,” First Amendment News 366 (Feb. 8)

Zick on public protests and other topics

- Timothy Zick, “Public Protest and Governmental Immunities,” Southern California Law Review (2024)

This Article presents the findings of a quantitative and qualitative study of the application of qualified immunity and other governmental immunities in the context of public protest. Relying on three unique datasets of federal court decisions examining First Amendment and Fourth Amendment claims, the Article concludes that public protester plaintiffs face an array of obstacles when suing state, local, and federal officials for constitutional injuries. Quantitative findings show that protesters’ claims are frequently dismissed under qualified immunity doctrines and that plaintiffs also face strict limits on municipal liability, new restrictions on First Amendment retaliation claims, and the possible extinction of monetary actions against federal officials. Qualitatively, the study shows protesters’ rights are under-developed in several respects, including recognition of the right to record law enforcement and limits on law enforcement’s use of force. The study lends additional support and new urgency to calls for qualified immunity reform or repeal, as well as reconsideration of other governmental immunities. It also concludes that much more than money damages for injured plaintiffs is at stake. Lack of adequate civil remedies may significantly chill future public protest organizing and participation.

Social media platforms and censorship

- Timothy Zick, “The Supreme Court Will Decide if Texas Is Allowed to Kill the Internet,” Slate (Sept. 29)

When social media platforms like Facebook and YouTube moderate content, are they engaged in protected speech? Or are they engaged in an invidious form of censorship? The answer, which lies at the heart of a pair of cases the Supreme Court agreed to hear on Friday, could fundamentally alter the nature and operation of social media platforms and the internet itself.

Reacting to complaints from the political right that large social media platforms including Facebook and YouTube actively censor conservative views, Texas and Florida enacted laws prohibiting the platforms from removing, deleting, or deplatforming speech or speakers based on viewpoint. The laws differ in some respects, but both create a legal cause of action against social media platforms that engage in any of the laws’ defined methods of “censorship.” They also require that platforms provide an explanation for any posts “censored” and publicly disclose their guidelines for removing speech or speakers from the platforms.

‘So to Speak’ podcast interview with Kristen Waggoner

- “‘Are cakes speech?’ with Alliance Defending Freedom's Kristen Waggoner,” So to Speak (Oct. 12)

President, CEO, and general counsel of the Alliance Defending Freedom, Kristen Waggoner, joins us for a discussion on freedom of speech and religious liberty. ADF has played various roles in 74 U.S. Supreme Court victories and since 2011, has won cases before the Court 15 times.

According to its website, “ADF is the world's largest legal organization committed to protecting religious freedom, free speech, marriage and family, parental rights, and the sanctity of life.”

ADF has litigated many high-profile and controversial free speech cases, including the recent Supreme Court case involving a web designer who didn't want to be compelled to design websites for same-sex weddings. Before that, ADF litigated the 2018 Masterpiece Cakeshop case, which involved a cake designer who similarly didn't want to provide his services for same-sex weddings on religious grounds.

After the initial conversation was recorded, The Washington Post and The New Yorker released articles critical of ADF. Nico and Kristen recorded an additional, brief conversation to address these articles. That is included at the end of the podcast.

Related

- Ronald Collins, “Kristen Waggoner is the one to watch in First Amendment cases,” First Amendment News 263 (July 15, 2020)

Whittington to move to Yale Law School to direct new center on academic freedom

- Keith Whittington, “My Move to Yale Law School,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Oct. 16)

After spending more than two decades in the Department of Politics at Princeton University, I'm pleased to announce that I will joining the faculty of Yale Law School in the fall of 2024. At YLS, I also expect to be the faculty director of a new center focused on academic freedom and free speech issues.

I've been extremely fortunate to have been at Princeton, and I leave with nothing but good feelings and best wishes for my students and colleagues there. It is time to take on some new challenges, however, and I very much look forward to joining a new set of students and colleagues at Yale.

Yale Law School has an unparalleled role in shaping the legal academia and influencing policymakers, and I'm looking forward to finding my own niche there.

I'm not unmindful of the significance of this move at the present moment. YLS has, of course, had its own recent controversies regarding free speech and ideological diversity. Yale has notoriously been lacking in right-of-center public law faculty for decades. Co-blogger Josh Blackman says YLS is a failed academic institution. I hope not! But the lack of political diversity on elite law school faculties is unhealthy, and I'm glad to be able to do my small part to mix things up.

Related

- “Keith Whittington to Join Yale Law School Faculty,” Yale Law School (Oct. 16)

More in the news

- Eugene Volokh, “FIRE Letter to NYU School of Law About the Ryna Workman Pro-Hamas-Attack Speech Controversy,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Oct. 16)

- Ken Paulson and Jason Reineke, “Poll: States shouldn’t limit what professors teach,” Free Speech Center (Oct. 16)

- Sasha Volokh, “Taxing Nudity: Discriminatory Taxes, Secondary Effects, and Tiers of Scrutiny—part 2 in a series,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Oct. 16)

- Chris Eberhart, “‘Turtleboy’ blogger faces criminal charges from Massachusetts in First Amendment fight,” New York Post (Oct. 15)

- Ilya Somin, “Some Cancellations are Justified,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Oct.15)

- Joe Cohn, “Targeting students for disparate treatment based on protected class is not protected by academic freedom,” FIRE (Oct. 13)

- Eugene Volokh, “UK Home Secretary Calls for ‘Heavy Criminal Consequences’ for Various Pro-Hamas Speech,” The Volokh Conspiracy (Oct. 13)

- “The wisdom of the University of Chicago’s ‘Kalven Report’,” FIRE (Oct 12)

- Daniel Ortner, “Broad coalition supports FIRE’s challenge to New York’s online hate speech law before Second Circuit,” FIRE (Oct. 5)

2022-2023 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Review granted

- Vidal v. Elster (to be argued Nov. 1)

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier (to be argued Oct. 31)

- Moody v. NetChoice, LLC / NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton / NetChoice, LLC v. Moody

Pending petitions

- Porter v. Board of Trustees of North Carolina State University

- Alaska v. Alaska State Employees Association

- Speech First, Inc. v. Sands

- O’Handley v. Weber

- National Rifle Association of America v. Vullo

- Tingley v. Ferguson

State action

- Lindke v. Freed (to be argued Oct. 31)

Review denied

- Stein v. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Inc., et al.

- Blankenship v. NBCUniversal, LLC

- Center for Medical Progress v. National Abortion Federation

- Frese v. Formella

- Mazo v. Way

Free speech related

- Miller v. USA (pending) (statutory interpretation of 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c) advocacy, lobbying and protest in connection with congressional proceedings)

Previous FAN

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE or of Mr. Collins.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

The American people fact-checked their government

Facing mass protests, Iran relies on familiar tools of state violence and internet blackouts

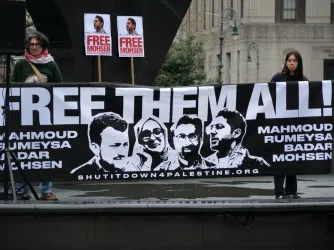

Unsealed records reveal officials targeted Khalil, Ozturk, Mahdawi solely for protected speech