Table of Contents

Eighth Circuit: Professor’s criticism of colleague did not violate the First Amendment

Shutterstock.com

Yesterday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit weighed in on a legal dispute between two faculty members of the University of Iowa, holding that one professor’s criticism of another did not violate the First Amendment.

FIRE filed an amicus brief, authored by professor Eugene Volokh and UCLA First Amendment Amicus Brief Clinic student Michael Quinan, urging this outcome.

FIRE’s brief supports Marc Linder, a law professor sued by James Brown, a medical professor aggrieved by Linder’s criticism of his expert testimony in a case involving “Big Pig.”

Brown v. Linder

In 2021, James Brown, a professor of urology at the University of Iowa, sued law professor Marc Linder over comments Linder made regarding Brown's expert testimony

Iowa regulators took action against Swift Pork — now part of one of the largest pork producers in the world — in 2016 over its policies on when employees could use the restroom. The company hired Brown, a urologist, to provide expert testimony about the health concerns implicated by the policy.

According to the lawsuit later filed by Brown, Linder — a labor law professor — opposed Brown’s testimony, believing it would harm workers. When Brown showed up for his deposition, Linder stood in the hallway with a shirt reading “People Over Profits.” He also criticized Linder publicly, arguing in an interview with the Cedar Rapids Gazette that Brown’s testimony “could have unleashed or helped to unleash terrible consequences for workers of Iowa.” In an opinion piece for the Daily Iowan, Linder argued that Brown was among the “hired guns” serving “private profit-making defendants” in violation of a state law. (The Iowa Ethics and Campaign Board disagreed, finding that Brown’s testimony did not violate state law.)

Linder was wrong about the extent to which the state can prevent its employees from offering expert testimony. State universities can’t prevent faculty members from serving as expert witnesses on the theory that their testimony contradicts the state. That would subject testimony across the political spectrum to viewpoint discrimination. Just ask faculty in Florida. There, last January, a federal court issued a scathing ruling rebuking efforts to prevent public university faculty from offering expert testimony critical of voting regulations backed by the DeSantis administration.

As a public employee, Brown retains the First Amendment right to speak as a private citizen on matters of public concern, including by offering testimony that his colleagues, employer, or state officials find objectionable.

Courts are, and should be, especially reluctant to attribute speech by faculty members to the institutions that employ them.

And that’s the same right that protects Linder’s criticism of Brown’s testimony. Someone who gives public testimony doesn’t just subject them to the opinion of the court, but to the court of public opinion.

Brown sued Linder, alleging that because Linder was a state employee, his criticism was retaliation that violated Brown’s First Amendment rights. But as the Eighth Circuit correctly explained, just being a state employee — even when people know you’re a state employee — doesn’t mean that you’re speaking for the state. In other words, not all speech by a professor is “under color of law” and attributable to their employer:

At the end of the day, we do not doubt that the public might regard a law professor’s views on expert testimony as particularly authoritative. Indeed, it is certainly possible that Linder’s occupation brought attention to, or elevated the credibility of, his criticism of Brown. Nonetheless, that Linder happens to work for a public university rather than a private one does not, by itself, mean that his conduct was under color of state law.

That’s the right result — and it’s especially important for faculty. Courts are, and should be, especially reluctant to attribute speech by faculty members to the institutions that employ them, even when faculty members reference their own jobs. Otherwise, institutions would have greater authority to limit what faculty members say in public.

As our amicus brief explained:

A professor similarly best serves the public in his public commentary, not by acting on behalf of the State, but rather by advancing what he personally understands to be the truth, based on his own personal academic expertise. In their scholarship and commentary, professors famously speak just for themselves, not for the university or the State more broadly.

This is because universities are collectives of people who disagree with one another. As the Supreme Court has explained, universities use the “robust exchange of ideas” to discover “truth out of a multitude of tongues, rather than through any kind of authoritative selection.”

Institutions of higher education too often attempt to restrict faculty speech because it references where they work (or because someone might figure out where they work), their institution’s name, or the unlikely possibility that someone might mistake a professor for a spokesperson.

But most people understand that faculty speak for themselves, not their institutions. And because Linder did not speak on behalf of his state institution, he couldn’t have violated the First Amendment, which binds only government actors, not private actors like Linder.

FIRE is grateful to professor Volokh and Michael Quinan for their work in authoring this brief.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

The American people fact-checked their government

Facing mass protests, Iran relies on familiar tools of state violence and internet blackouts

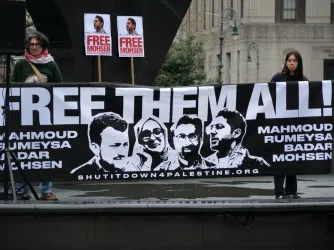

Unsealed records reveal officials targeted Khalil, Ozturk, Mahdawi solely for protected speech