Table of Contents

Rethinking Stanford’s approach to eliminating ‘harmful’ language

Michael Warwick / Shutterstock.com

Stanford University campus (via Shutterstock.com)

Earlier this month, the Wall Street Journal opined on a list of words and phrases from Stanford University’s Elimination of Harmful Language Initiative. “Parodists have it rough these days,” the Journal posited, “since so much of modern life and culture resembles the Babylon Bee.”

According to Stanford’s IT department, the EHLI is a “multi-phase, multi-year project to address harmful language in IT at Stanford.” The EHLI website, access to which now requires a Stanford email address and password, is “geared toward helping individuals recognize and address potentially harmful language they may be using.” The site was removed from public view after the list began making the rounds on social media last week.

By now, much has been written about the words and phrases Stanford removed from its website for their potential to cause harm. “That was insane!” isn’t palatable, because “This term trivializes the experiences of people living with mental health conditions.” What to do when referring to a whitelisted or blacklisted IP address? Try “allowlist/denylist,” because the former terms “[a]ssign value connotations based on color (white = good and black = bad), an act which is subconsciously racialized.” You get the idea. “American,” “dumb,” and “lame” are out, too.

The inherent infantilization of steering adults away from words and phrases like “tone deaf” and “mailman” is troubling.

Last week, after the list became public and backlash mounted, Stanford announced it would conduct a review of the guide. The statement from Chief Information Officer Steve Gallagher clarified the website does not represent Stanford University policy. “It also does not represent mandates or requirements,” Gallagher wrote. The list simply provides “suggested alternatives.” “But, we clearly missed the mark,” Gallagher concedes. “We value the input we have been hearing, from a variety of perspectives, and will be reviewing it thoroughly and making adjustments to the guide.”

While FIRE is, of course, relieved to hear these alternatives are not required, the inherent infantilization of steering adults away from words and phrases like “tone deaf” and “mailman” is troubling. By prematurely wading into conversations and deeming words and phrases offensive on behalf of its adult students, Stanford deprives its community members the chance to build resilience and talk through the issues of the day without having to constantly worry about stepping on rakes.

We think institutions of higher education better serve students by not inserting themselves in language debates that are almost certain to produce a “Streisand effect,” occurring when more attention is brought to forbidden words and phrases in the effort to silence them. FIRE recommends a culture of trust, not coddling. Why?

Studies reveal unintended consequences of efforts to reduce linguistic harm

Efforts to raise awareness of harmful words may be well intentioned. In a 2019 study, Melanie J. McGrath and others found that people who possess more inclusive understandings of abuse, bullying, prejudice, and trauma tended to be emotionally empathic, and focused on harm and care.

Furthermore, people often cite concerns not about their own negative emotional reactions, but about the potential negative reactions of others — a classic example of the third-person effect. However, Stanford IT administrators may inadvertently amplify perceptions of harm, especially among students who are already struggling emotionally.

In a recent paper, April Bleske-Rechek and colleagues discuss the results of two studies testing the influence of environmental and personal factors on U.S. college students’ perceptions of harm induced by words.

In the environmental study, the researchers found that including one sentence warning students they might encounter harmful language caused them to perceive ambiguous phrases as harmful. In other words, the prime increased the harm it aimed to prevent. This is a well-documented pattern in the literature on trigger warnings.

In the personal study, they found that students high in negative emotionality experienced greater feelings of hurt and anxiety in response to ambiguous statements. These findings align with a 2022 study in which Jared Celniker and colleagues reported that cognitive distortions — such as catastrophizing, personalization, and overgeneralization — predicted students’ belief that words can cause harm.

And in a 2011 study, Asian-American students who perceived ambiguous comments as evidence of racism experienced higher anxiety than those who did not perceive racism in the same situations. These findings are not surprising when we consider the extensive evidence that individual differences shape subjective reactions to potentially stressful events.

Although we advance psychological science by broadening our understanding of diverse human experiences, expanding our conception of what constitutes harm may have unintended consequences for the very populations we intend to serve.

‘Concept creep’ at Stanford

In 2016, Nick Haslam coined the term “concept creep” to describe the tendency for the semantic range of harm-related concepts to expand over time. In other words, the meaning of concepts such as “trauma,” “bullying,” and “violence” has broadened to include ever milder, subtler phenomena.

The meaning of concepts such as “trauma,” “bullying,” and “violence” has broadened to include ever milder, subtler phenomena.

Stanford’s list of “harmful” words exemplifies concept creep for two reasons: first, the list labels as harmful words that most people do not consider harmful; second, the list lumps all of the words together, as though they are equally harmful. Stanford IT states, “We are not attempting to assign levels of harm to the terms on this site.” Indeed, if harm is in the eye of the beholder, who is Stanford to determine how harmed you feel?

Yet we can rely on likely consensus to gauge the offensiveness of words. Calling someone a “retard” surely is more widely perceived as offensive than, say, calling someone “brave.” Stanford administrators seem to believe that it doesn’t matter whether everyone, or just one person, finds a word harmful. But if we don’t consider how many people feel harmed, we risk creating what Benjamin G. Bishin calls a “tyranny of the minority.”

Stanford’s attempt to “eliminate many forms of harmful language” may be detrimental to the academic enterprise. The quest for knowledge requires the free exchange of ideas. Yet it may hinder that pursuit to sensitize students to the subtle harms they may feel when exposed to words such as “tribe,” “American,” and “mankind” that are, ironically, intended to create a more inclusive environment.

We understand that Stanford, in honoring its commitment to diversity and inclusion, wishes to raise awareness of words and phrases that members of historically marginalized groups may interpret differently. Yet honoring this commitment requires considering potential unintended negative consequences that such efforts may have on the very populations they intend to serve.

Stanford states, “We also are not attempting to address all informal uses of language.” However, students and faculty, in attempting to be more inclusive, may become more vigilant about monitoring people’s language, and more likely to avoid not only the listed words, but also any others that might be perceived to cause some degree of psychological harm. This may create a spiral of silence on Stanford’s campus.

The bottom line

Stanford IT says the initiative is intended to reduce prejudice and improve social norms surrounding the treatment of historically marginalized groups. However, raising awareness of “harmful” words may sensitize students to subtle signs of potential prejudice so they become hypervigilant, prone to confirmation bias, and more likely to see themselves as emotionally ill-equipped to function in a world they perceive as full of threats.

Although Stanford may be correct that some feel emotional pain when they hear the listed words, they are wrong to try to prevent such pain. Top-down attempts to eliminate “harmful” language prevent students from gaining valuable exposure that may desensitize them, because, when spoken on campus, the words are not likely to be accompanied by physical threats, which are — and should be — prohibited by the university.

Stanford students are adults whose academic achievements have earned them spots at one of the most intellectually rigorous universities in the country. They do not need an institutional authority to explain why they might wish to forgo using certain harmful words. There is greater dignity in being trusted to respond constructively to offensive language than there is in being protected from it.

FIRE defends the rights of students and faculty members — no matter their views — at public and private universities and colleges in the United States. If you are a student or a faculty member facing investigation or punishment for your speech, submit your case to FIRE today. If you’re faculty member at a public college or university, call the Faculty Legal Defense Fund 24-hour hotline at 254-500-FLDF (3533). If you’re a college journalist facing censorship or a media law question, call the Student Press Freedom Initiative 24-hour hotline at 717-734-SPFI (7734).

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

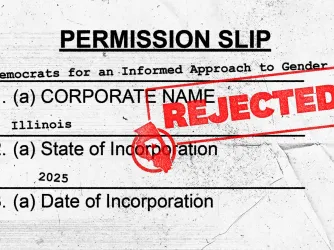

LAWSUIT: Illinois law blocks Democratic dissenters from operating without party elites’ permission

The Alex Pretti shooting and the growing strain on the First Amendment

Facing mass protests, Iran relies on familiar tools of state violence and internet blackouts