Table of Contents

UConn’s disdain for due process rights evident in hearing transcript

singh_lens / Shutterstock.com

Last week, I wrote about an unusually strong opinion from the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut finding that a University of Connecticut student accused of sexual misconduct had shown a “clear likelihood of success” on his claim that UConn violated his constitutional due process rights.

Now, FIRE has obtained a transcript of the status conference that led to that opinion, and it sheds considerable light on what may have motivated U.S. District Judge Michael Shea to knock out a powerful 13-page opinion in defense of due process later that same day.

As I explained last week, one of the critical issues in this case is that the university refused to hear from several of plaintiff’s witnesses who were prepared to testify about matters directly concerning the complainant’s credibility:

John told UConn’s investigator that after John and Jane left the party, they piled — with a group of other friends — into the backseat of another student’s car to go for pizza. According to John, Jane sat on his lap in the car and began to grind against him. Jane denied this, but according to the witness statement of his friend in the front passenger seat, “I could also feel the knees of the girl sitting on [John Doe’s] lap through the back of my seat. I could feel that she was moving back and forth. It was clear to me that these movements on [John Doe’s] lap were sexual.” A witness in the back seat gave a similar statement: “While we were driving to [the pizzeria], the girl sitting on [John Doe’s] lap was moving like she was dancing on his lap, moving her body like moving from her waist. I didn’t want to stare at them.”

Now, of course, these witness statements do not speak to whether the later sexual encounter in Jane’s dorm room was consensual — but since she denied the behavior in the car, they speak to her credibility about the evening’s events. This evidence never saw the light of day, however, because UConn’s investigator excluded the statements of both of these witnesses from his report, and the hearing officers also refused to allow them to testify at the plaintiff’s hearing.

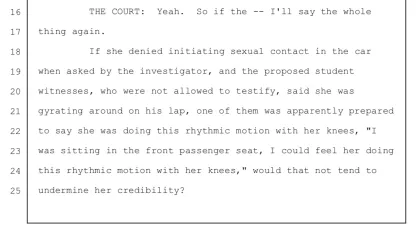

Throughout the conference call with the parties’ lawyers, the judge repeatedly expressed his concern with the fact that these witnesses had not been permitted to testify or even provide written statements:

In response, the university’s lawyer repeatedly tried to argue that the witnesses’ testimony was not relevant.

First, she argued that their testimony was irrelevant because they only witnessed the consensual sexual activity in the car, not the allegedly non-consensual sexual activity in the bedroom. But the judge disagreed — if the complainant lied about initiating sexual activity in the car, that spoke directly to her credibility, and the two parties’ credibility is the central issue in the case.

When that argument failed, the university’s lawyer then argued that their testimony was irrelevant because they had not actually watched the alleged lap dance (the front-seat witness felt the complainant’s knees moving rhythmically against the back of his seat; the back-seat witness looked away in discomfort when he realized what was going on).

At this point, the judge became openly exasperated, telling UConn’s lawyer “[C]ome on. I thought you were going to be serious about this… That’s not a serious answer.”

Eventually, the judge moved on to his concern with another part of the procedure: the fact that UConn’s hearing officers relied on the earlier, written statements of several of the complainant’s witnesses who did not actually testify at the hearing. This, the judge worried, did not provide the plaintiff with a meaningful opportunity to confront the witnesses against him.

The judge noted that other federal courts had found cross-examination necessary to due process in the campus judicial setting (the Second Circuit has yet to address the issue), but he ultimately did not even need to express an opinion on that to find that UConn’s procedure was deficient. Asking UConn’s lawyer to defend the university’s procedure, he said:

I asked the plaintiff’s attorney, Michael Thad Allen, if he had been surprised by the university’s seemingly cavalier attitude towards the plaintiff’s rights at the status conference.

“I’m not surprised, because this was how they conducted the entire investigation and hearing,” Allen said. “The person who did seem surprised was the judge, when UConn effectively admitted that their approach was simply to believe the accusing student no matter what the other witnesses had to say.”

Just hours after the status conference, the judge issued his ruling that by excluding plaintiff’s witnesses and denying him any opportunity to confront the complainant’s witnesses, UConn had likely violated the plaintiff’s due process rights.

FIRE will keep you updated on this case as it develops.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

He refused to censor his syllabus — so Texas Tech cancelled his class

Fandom’s lighthouse in a sea of censorship

FIRE statement on Stephen Colbert’s James Talarico interview and continued FCC pressure