Table of Contents

Unfurling the constitutionality of flag restrictions on government flagpoles

Shutterstock.com

Last week in the city of Hamtramck, Michigan, the city council unanimously passed a resolution prohibiting “any religious, ethnic, racial, political, or sexual orientation group flags to be flown on the City’s public properties.” Discussion and reporting about the vote focused on raising (or rather, not raising) the Pride flag, and the vote itself was widely reported as “a ban on the Pride flag.”

Now the question is: “Is the resolution constitutional?” The short answer: probably.

Broadly speaking, the First Amendment restrains the government from restricting others’ speech, but it doesn’t apply to the government’s own speech. Government entities, like city or county councils, can generally say whatever they want — advocating favored policies, taking positions, and promoting some views but not others.

Some flag-related policies provide examples of governments speaking for themselves.

Take, for instance, another recent flap over the Pride flag. In February, the city council in Huntington Beach, California, voted to limit the flags displayed on city government buildings to only the American, POW/MIA, state, county, and City of Huntington Beach flags.

A city employee confirmed that, before the vote, the Pride flag was the only other flag approved for display by the Huntington Beach city council. The city council originally approved flying the Pride flag in May 2021, and this more recent vote reverses that decision. Huntington Beach’s city council closely controls the flags that fly on city facilities — the council has not opened up city-owned flagpoles to any group that wishes to raise its own flag.

Cities — and counties and similar entities — may select and designate specific flags to fly on government-owned flagpoles, rather than, say, opening the poles to members of the public to raise flags of their choice. In the former case, in which flagpoles are not open to public use, the flags represent a message from the government itself. In making decisions about which flags to fly, the government thus “regulates” only its own speech.

But as a recent Supreme Court decision illustrates, sometimes flags aren’t government speech at all, and prohibiting citizens from raising their own flags on public flagpoles based on viewpoint, message, or the identity of the sponsor can violate the First Amendment.

Because the flag was not government speech, Boston officials violated Shurleff’s First Amendment rights when they denied his flag request based on the viewpoint his flag expressed.

In 2017, for example, Harold Shurtleff wanted to hold an event on City Hall Plaza outside of Boston City Hall, and at his event, he wanted to raise what he described as the “Christian flag.” The city of Boston regularly allowed outside groups to hold ceremonies and events at the plaza, and groups could fly a flag of their choosing on one of the city’s flagpoles during their events. Previous groups had raised Pride flags, banners honoring emergency medical service workers, and other flags, and the city’s practice was to approve these requests without exception.

However, Shurtleff’s request to raise his chosen flag was refused. The city argued that allowing Shurtleff’s “Christian flag” would violate the Constitution’s Establishment Clause prohibition against the government endorsing a religion. The city told Shurtleff he could hold his event, but he could not raise his chosen flag.

Shurtleff sued the city, and the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2022, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Shurtleff’s favor, explaining that the city’s application and approval regime for events and flags showed the flags were speech not of the city but of the people who chose to raise them: “All told, Boston’s lack of meaningful involvement in the selection of flags or the crafting of their messages leads the Court to classify the third-party flag raisings as private, not government, speech.” Because the flag was not government speech, Boston officials violated Shurleff’s First Amendment rights when they denied his flag request based on the viewpoint his flag expressed.

So, what about Hamtramck?

The city has a number of city-owned flagpoles along Joseph Campau Ave., and in 2013, Hamtramck’s city council approved the raising of flags “that represent the international character of the City” on the city’s flagpoles. Hamtramck has a large population of foreign-born residents and the highest percentage of immigrants among any city in Michigan.

This new resolution appears to build on the 2013 resolution by further clarifying what flags are allowed on the city’s flagpoles. Similar to the Huntington Beach resolution, Hamtramck’s resolution limits the permitted flags to “the American Flag, the flag of the State of Michigan, the Hamtramck Flag, the Prisoner of War flag and the nations’ flags that represent the international character of our City.” Thus, the city appears to actively control what flags are raised to transmit its own messages.

As long as the city is solely controlling its own speech, its restrictions should fall within constitutional boundaries.

One potential problem with the resolution is the lack of clarity of what it means for a flag to be “flown” on the city’s “public properties.” Under the Constitution, Hamtramck cannot, for instance, prohibit private citizens from carrying or displaying a flag on public sidewalks, in public parks, or in other public forums — or, for that matter, on their own private property — based on its disapproval of the flag’s message. But to the extent this language refers only to what flags the city decides to fly on its own flagpoles, it’s likely constitutional.

That appears to be the intent of the language when the resolution is viewed as a whole, including an earlier reference to “City flagpoles” and a statement that the city “does not want to open the door for radical or racist groups to ask for their flags to be flown.”

As long as the city is solely controlling its own speech, its restrictions should fall within constitutional boundaries.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

The American people fact-checked their government

Facing mass protests, Iran relies on familiar tools of state violence and internet blackouts

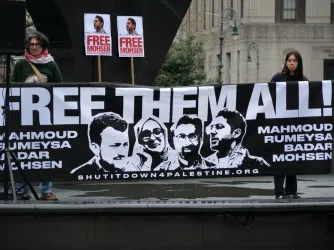

Unsealed records reveal officials targeted Khalil, Ozturk, Mahdawi solely for protected speech