Table of Contents

Why repealing or weakening Section 230 is a very bad idea

klevo / Shutterstock.com

This is the second installment in a two-part series on Section 230. This part focuses on Section 230’s importance to free speech on the internet and addresses some common misconceptions about the law. See Part 1 for an overview of Section 230’s text, purpose, and history.

Section 230 made the internet fertile ground for speech, creativity, and innovation, supporting the formation and growth of diverse online communities and platforms. Today we take for granted that we can go online and find many different places to speak our minds, connect with people, and share and view photos, videos, music, art, and other creative content.

Repealing or weakening Section 230 would jeopardize all of that.

As I explained in Part 1, Section 230 “gives ‘interactive computer services’ — including discussion forums, hosted blogs, video platforms, social media networks, crowdfunding sites, and many other services that host third-party speech — broad immunity from liability for what their users say.” The statute “also grants the services broad immunity from liability for declining to host, publish, or platform third-party speech.”

Without Section 230, websites would be left with a menu of unattractive options to avoid lawsuits over their users’ speech. Many would likely change their business model and stop hosting user-generated content altogether, creating a scarcity of platforms that sustain our ability to communicate with each other online. This changed landscape would entrench the dominance of large platforms that can afford to defend endless lawsuits and devote extensive resources to moderating vast amounts of user content.

Your guide to Section 230, the law that safeguards free speech on the internet

FIRE delves into Section 230’s text, purpose, and history and its importance to free speech on the internet and address some common misconceptions about the law.

Surviving platforms would moderate content more aggressively and maybe even screen all content before it’s posted. That isn’t a recipe for a thriving, free-speech-friendly internet. If you think Twitter and Facebook go too far with content moderation now, just imagine how much more aggressively these platforms would moderate if threatened with liability for users’ speech. None of these platforms have the capacity to carefully review all content, let alone make consistently accurate judgments about its legality. They would likely tweak their algorithms, which already produce lots of false positives, to take down even more content.

Section 230 doesn’t just protect platforms from liability for unlawful content created by others: It also facilitates the prompt dismissal of frivolous lawsuits, often in cases that don’t even involve unlawful speech. Without Section 230, many of these lawsuits would still cause platforms major headaches by requiring them to engage in extensive discovery and pretrial motions.

What’s more, pre-approving posts would destroy an essential feature of so many websites: their users’ ability to interact with each other in real time, to comment on current events while they’re still current. It would also limit platforms’ growth, constraining the amount of new content based on a platform’s capacity to review it.

You might ask: Can’t platforms just take a hands-off approach like CompuServe? Recall from Part 1 that, before Section 230 was enacted, a federal court ruled CompuServe — which did not moderate its forums’ content — couldn’t be held liable for allegedly defamatory speech posted by a third party in one of those forums.

But even a platform that took that approach would be liable for posts they knew or had reason to know about. That still means reviewing an unmanageable number of complaints about allegedly unlawful content, not to mention maintaining a speech-limiting notice-and-takedown system. Inevitably, complaints would come from people simply annoyed or offended by a user’s speech, and many platforms would take the easy, risk-averse way out by summarily removing challenged content rather than thoroughly investigating the merit of each complaint.

The answer isn’t to harness government power to control private platforms’ editorial decisions. Repealing or undermining Section 230 would lead only to less expressive freedom and viewpoint diversity online — to the detriment of us all.

Plus, one purpose of Section 230 is to promote platforms’ self-governance. Platforms’ exercise of editorial judgment over the content they host is itself expressive, and protected by the First Amendment. It’s part of how many online communities define themselves and how people decide where they want to spend their time online. A discussion forum that wants to be “family friendly” may decide to ban profanity. A baseball forum may limit posts that aren’t about baseball. And an NRA message board may remove messages opposing gun rights. Many platforms restrict spam and self-advertising, for example.

Large social media companies can be frustratingly arbitrary in their content moderation. But if every online platform were a free-for-all, we would no longer benefit from the great diversity of communities and discussion spaces on the internet that cater to different people’s interests and desired user experiences.

Section 230 is under threat

Presidents from both major political parties have called for abolishing Section 230. Other politicians want to amend the law, and some have already succeeded in chipping away at it (with unconstitutional legislation).

Such efforts to narrow Section 230’s scope or make its legal protections conditional would produce negative consequences for free speech. Carving out certain categories of speech from Section 230’s protection, for example, would lead platforms to restrict more speech to minimize legal risk.

We’ve already seen that happen with enactment of the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act and Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, which, in addition to criminalizing the online “promotion or facilitation” of prostitution and “reckless disregard” of sex trafficking, creates new civil liability and exposure to state prosecutions in connection with those and related offenses. This overbroad law goes well beyond targeting involvement in coercive sex trafficking: It restricts speech protected by the First Amendment.

Social media platforms are now heavily incentivized to suppress speech related to prostitution rather than risk civil or even criminal liability. That’s exactly what happened immediately after SESTA/FOSTA became law. Reddit banned multiple subreddits related to sex, none of which were dedicated advertising forums. Craigslist completely shut down its personals section, saying it couldn’t risk liability for what users post there “without jeopardizing all our other services.”

Politicians and critics on both the left and the right unhappy with how social media companies moderate content often blame Section 230.

As the Woodhull Freedom Foundation, Human Rights Watch, and other plaintiffs challenging SESTA/FOSTA argue, “Websites that support sex workers by providing health-related information or safety tips could be liable for promoting or facilitating prostitution, while those that assist or make prostitution easier—i.e., ‘facilitate’ it—by advocating for decriminalization are now uncertain of their own legality.”

In 2021, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg proposed making Section 230’s legal protections contingent on having “adequate systems” in place for “identifying unlawful content and removing it.” But as the Electronic Frontier Foundation explained, that would benefit wealthy platforms like Facebook at the expense of countless other platforms, as the “vast majority of online services that host user-generated content do not have the technical, legal, or human resources to create systems that could identify and remove unlawful content.” It would potentially require pre-screening content, and inevitably lead to more removal of lawful speech, given the high failure rate of both human reviewers and algorithms.

Common complaints and misconceptions about Section 230

Politicians and critics on both the left and the right unhappy with how social media companies moderate content often blame Section 230. Conservatives complain that it allows platforms to censor conservative voices with impunity, while liberals criticize the law for allowing platforms to duck responsibility for hosting “hate speech,” extremist content, and mis- and disinformation. But many of the attacks on Section 230 are misguided.

“Section 230 is just a handout to Big Tech!”

The conversation around Section 230 often revolves around large social media companies like Twitter and Facebook. But the law protects all internet services and platforms that host or share others’ speech online, from Wikipedia, to Substack, to Indiegogo, to OkCupid, to Yelp, to the smallest blogs and websites. Importantly, the immunity provision also applies to any “user of an interactive computer service.” Courts have held that this language protects individuals who share content by, for instance, forwarding an email or tweeting a link to an article.

Eliminating Section 230 would actually stifle Big Tech’s competition, disproportionately affecting startups and smaller websites with less money and resources to moderate content and fend off lawsuits. This, in part, explains why Zuckerberg, the CEO of the largest social media platform in the world, supports Section 230 reform.

“Section 230 might have been important when the internet was getting off the ground in the 1990s, but it has outlived its usefulness.”

Section 230 is arguably even more necessary today. To expect platforms to review all user content was unrealistic even in the ’90s when many forums hosted thousands of new posts each day. Today, platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and WhatsApp serve billions of users. Hundreds of millions of tweets are posted on Twitter each day. More than 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute. While automated content moderation is more common today, it’s far from perfect, and many smaller websites do not have access to advanced algorithmic tools.

The internet is still evolving and expanding. And it needs Section 230 to do so.

“Social media platforms shouldn’t evade liability for hosting hate speech, misinformation, and other speech that causes harm.”

Anyone who raises this objection to Section 230 needs to brush up on the First Amendment, which protects the overwhelming majority of speech labeled “hate speech” or “misinformation.” That means platforms still wouldn’t be liable for hosting this speech if Section 230 were revoked. The First Amendment would continue to protect them. But invoking that protection could require costlier and more protracted litigation in many instances, which would have to be waged on a case-by-case basis.

“Section 230 requires platforms’ content moderation to be fair and neutral.”

No, it doesn’t. In fact, a neutrality requirement — which has support in Congress — would raise First Amendment issues by providing immunity only to those platforms that moderate speech the way the government prescribes.

Free Speech and Social Media

Social media companies wield immense power to shape and inform important national debate. But some have gone too far in regulating the speech of their users. Here's what you need to know.

As private entities, social media platforms (and other websites) have a First Amendment right to exercise editorial discretion in deciding what speech to host, free from government coercion. Far from requiring neutrality, Section 230 provides extra protection to the right to editorial discretion to promote development of a wide variety of online communities.

Besides, a legislatively imposed fairness or neutrality requirement would itself be impossible to enforce fairly. The terms “fair” and “neutral” are vague, subjective, and ripe for abuse. A platform’s motive for restricting a given piece of content is not always clear. Where one person sees a straightforward application of the rules, another will see politically biased censorship. Imposing a neutrality requirement on topic- or viewpoint-based platforms would be especially absurd. Would a cycling forum that removed posts saying “biking sucks” also have to take down posts about how great biking is, so it could remain “neutral”?

That’s why Section 230(c)(2)’s protection of the editorial discretion to to refuse, block, or drop content rests principally on what the service provider considers objectionable. Any attempt to impose fairness or neutrality, or any other metric, would improperly substitute the government’s judgment for the service’s constitutionally protected editorial discretion.

“Section 230 protects platforms, not publishers. Social media companies that engage in extensive content moderation are acting as publishers and don’t find shelter under Section 230.”

This claim is a close cousin of the “neutrality” objection. It’s akin to saying platforms lose Section 230 protection for doing the very thing Section 230 protects. As explained, the law’s purpose is to immunize platforms from liability for users’ speech while also protecting their right to do as much or as little content moderation as they wish. When determining if Section 230 applies, the relevant question isn’t whether a platform is acting as a “platform” or “publisher.” It’s whether somebody other than the online service created the content in question and whether anything done to it by the service created the grounds for liability to apply.

“Print publishers can be liable for content they publish. Why should digital platforms get special privileges?”

When digital platforms create and offer their own content, they can be liable just like print publishers. Similarly, if they alter or contribute to a third party’s content and, in so doing, create the basis for alleged liability, Section 230 immunity may not apply. But absent such responsibility, in whole or part, for creating or developing the content, digital platforms are more like libraries, newsstands and bookstores.

Again, in that context, the enormous amount of content posted online makes reviewing all of it an effectively impossible task. Also, within the online sphere, Section 230 treats all publishers the same. It doesn’t matter if you’re a social media company, news outlet, or a blog. Many print publishers, including newspapers, also produce content online, where they receive, for any third-party content they host, the benefit of the same Section 230 protections as any other website.

We need to preserve the foundation for free speech on the internet

Section 230 is no less important to online free speech today than it was upon its enactment almost three decades ago.

Certainly, there are legitimate concerns about how a handful of social media platforms dominate the online speech market and/or may overregulate their users’ speech. These companies’ concentrated power makes their content moderation policies more consequential, giving them significant influence over public discourse. FIRE has taken platforms like Twitter to task for policies and decisions that undermine a culture of free expression.

But the answer isn’t to harness government power to control private platforms’ editorial decisions. Repealing or undermining Section 230 would lead only to less expressive freedom and viewpoint diversity online — to the detriment of us all.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

The American people fact-checked their government

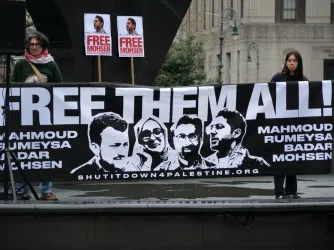

Facing mass protests, Iran relies on familiar tools of state violence and internet blackouts

Unsealed records reveal officials targeted Khalil, Ozturk, Mahdawi solely for protected speech