Table of Contents

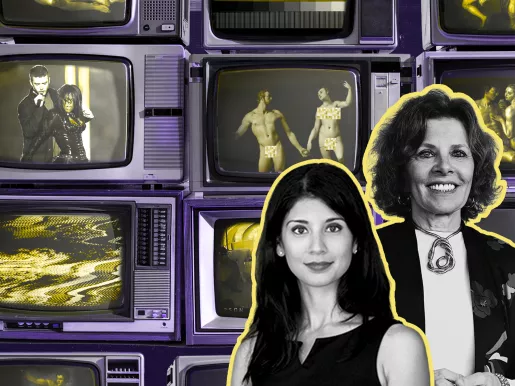

So to Speak Podcast Transcript: 'Defending pornography'

Note: This is an unedited rush transcript. Please check any quotations against the audio recording.

Nico Perrino: Welcome back to So to Speak, the free speech podcast where every other week we take an uncensored look at the world of free expression through personal stories and candid conversations. I am, as always, your host, Nico Perrino.

It has been remarked that censorship is the strongest drive in human nature, with sex being a weak second. But what happens when these two primordial drives clash? Does censorship or sex win out? On today’s show we are discussing pornography. Is it protected by the First Amendment’s guarantees for free speech, and should it be? And is censoring pornography, regardless of its constitutionality, good or bad for women?

We have two esteemed guests joining us today for this discussion. Nadine Strossen is an Emeriti professor at New York Law School, a former president of the ACLU, a senior fellow at FIRE, and the author of the book that serves as the centerpiece of today’s discussion. That book is, “Defending Pornography: Free Speech, Sex, and the Fight for Women’s Rights.” The book was first released in 1995 before being reissued in 2000, and then reissued again this year with a new preface. Nadine, welcome onto the show and congratulations.

Nadine Strossen: Thank you so much. Glad to be back. Well, actually condolences. I wish the book weren’t still relevant.

Nico Perrino: And we also are joined by Mary Anne Franks. She is a law professor at George Washington University. She is the author of the book, “The Cult of the Constitution: Our Deadly Devotion to Guns and Free Speech,” and she has another book due out in October entitled, “Fearless Speech: Breaking Free from the First Amendment.” Professor Franks, welcome onto the show.

Mary Anne Franks: Thanks so much for having me.

Nico Perrino: All right. So, I think we need to start here by doing our best, if it’s at all possible, to define pornography. Is it one of those things like obscenity that you know it when you see it? There’s a lot of discussion right now about book bans, book challenges. Often the justification for banning or challenging a book is that they’re pornographic. Nadine, I think as the author of the book, we will start with you. How do you think about pornography?

Nadine Strossen: Well, the dictionary definition relates to the entomological origin of the word, which is expression about sexual workers, about prostitutes. And it is generally used, according to most dictionary definitions, to refer to sexually explicit or sexually suggestive expression, which means words and/or images that are intended to be, or have the effect of being, sexually arousing.

What’s really important to note is that the term, “pornography,” has no legal significance with one exception. In other words, the supreme court has never said, “Pornography that satisfies that dictionary definition is unprotected,” but it has used the term, “Child pornography,” to refer to a very different subset of sexual expression, namely sexually explicit expression that is created by using an actual minor. And for that reason, for the sake of protecting the minors against abuse and exploitation, child pornography may be outlawed, and I certainly support that conclusion.

In every day speech, Nico, and you will observe this if you pay attention to many debates that are going on now, including about school curricula and about library books, people tend to use the term, “pornography,” and from now I’m going to drop the scare quotes, but just imagine they are always there because of this lack of precision. People tend to use it as a stigmatizing term. Whatever sexual expression they don’t like they call pornography. I quote Von Whit in my book as saying, “What terms me on is erotica. What turns you on is pornography.”

And there’s one other definition that’s really important because that was a focus of my book. It was responding to arguments that were very widely accepted among a certain segment of feminists who were usually referred to as radical feminists. The best known were Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon. They created a model law targeting pornography that they defined as, “The sexually explicit subordination of women.” So, essentially it outlawed sexual expression that was demeaning or degrading or dehumanizing to women.

Nico Perrino: And I want to get to Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon here in a bit, but I just want to ask a clarifying question. So, it’s expression or depictions that arouse someone sexually. So, a book on human biology or reproduction wouldn’t theoretically fall within your definition.

Nadine Strossen: Well, the dictionary definition, but the dictionary definitions are, “intended to or have the effect of.” So, I’ve read about people who are turned on by underwear catalogs, for example. Maybe somebody is turned on by a biology book. But basically, for all practical purposes, it’s any sexual or seminude or nude expression that somebody objects to. They tend to use the term pornography and therefore say we should do something about it, including censoring it on the internet, making it inaccessible to kids, removing it from library and curricula and so forth.

Nico Perrino: Yeah. And Professor Franks, how do you see it?

Mary Anne Franks: I think I certainly agree with Nadine that the definition has a lot of slipperiness to it because it really does depend on the context. There’s the question of what the law wants to recognize as pornography, and certainly we can talk more about that ordinance that does have a very specific definition of what pornography is, but I think as kind of a general matter we do think of it as being sexually explicit imagery as opposed to I think speech. Although, I do think that is to say verbal, oral writings or audio material.

But of course, that has become contentious too because there are an increasingly large number of things that are being referred to as pornographic, including books nowadays too. So, it really does matter who are you talking to and what are they trying to accomplish. But I think as a working definition, something about the sexually explicitly nature, something about the prurient nature, I think is important for determining what pornography is.

Nico Perrino: Cool.

Nadine Strossen: May I throw in one other term here, which is really important, and that is the term obscenity? Because that is the subset of sexual expression that the supreme court has said is unprotected beyond First Amendment protection solely based on its content. Unlike child pornography which is unprotected based on how it is produced. And Mary Anne, is it okay if we’re on a first-name basis, by the way?

Nico Perrino: I think you two know each other better than I know Professor Franks.

Nadine Strossen: So, Mary Anne alluded to one of the three elements that are required to satisfy the supreme court’s definition of constitutionally unprotected obscenity, and that is the material taken as a whole considered, according to contemporary community standards, has to appeal to the prurient interest in sex. Which the supreme court “defined,” I’m putting that word in quotation marks, as, “A sick or morbid interest in sex,” as opposed to a normal and healthy interest in sex. Number two, the material, again taken as a whole, under contemporary community circumstance has to be patently offensive as defined explicitly in law. And third, and all three of these have to be satisfied, under national standards, the material lacks serious literary, artistic, political, and scientific value.

So, it’s really a small subset of all sexual expression, all expression that you might consider to be pornography, that lacks First Amendment protection according to the supreme court. That said, I and know importantly many supreme court justices and I think a strong consensus of First Amendment experts, is that the obscenity exception itself is not justified under the First Amendment, but I want to emphasize how small it is compared to the concept of pornography.

Nice Perrino: So, let’s clarify for our listeners here. If we’re talking about pornography and its protection, or lack thereof, under the First Amendment, we’re generally talking about two categories: obscene speech, using the definition you just laid out, and child pornography. Everything other than that is protected?

Nadine Strossen: Yes.

Mary Anne Franks: Not quite.

Nico Perrino: Oh, good. A disagreement.

Nadine Strossen: And actually, I agree. I said yes too quickly, but I’d like to hear Mary Anne.

Mary Anne Franks: I think that the categories are useful, the sort of guides, to say that broadly speaking, yes, we’ve got this obscenity exception, which I think is worth delving into, and we’ve got the child sexual exploitation subset, which is actually more underinclusive than I think the average person knows. That is to say it’s not just any naked picture of a minor. It has to be a very specific kind of presentation of that minor in a sexual context. So, I think it’s important to know what the boundaries of that are.

But because of the work that I’ve done on sexually explicit representations of real people, sometimes called revenge porn or nonconsensual pornography, for reasons that relate to privacy, we can say that that, even if we conventionally call that pornography, that can be prohibited consistent with the First Amendment. The supreme court hasn’t had a case directly about revenge porn, but there have been five state supreme court decisions that have said this is a category that is combatable with the First Amendment.

And the attempt that was made in the Illinois case where that was found to be true, there was a petition for certain the supreme court said no. So, I think that’s pretty definitive to say that that category is also something we can regulate in a way that’s consistent with the First Amendment.

Nico Perrino: And you’ve done a lot of work on revenge porn. I just want to clarify on the revenge porn point. This is pornography that involves, in some cases for example, intimate partners, maybe they had a relationship, the relationship goes south, one of the partners shares an explicit photo of the other partner as a way to kind of get back at them, right?

Mary Anne Franks: Sometimes. So, that’s one of the reasons why activists and advocates in the field don’t like the term revenge porn. It’s actually both because the revenge part and the porn part. So, on the one hand, the pornography terminology is complicated for all the reasons we’ve just been saying because if there is kind of a moral valence to pornography, we really don’t want to attach that kind of moral valence to just a naked picture of someone because it may or not be something that should be considered immoral. But the theory of calling that pornography had more to do with the misuse of somebody’s image in that way to turn it into entertainment for strangers.

The revenge part has always been problematic because what you’re describing, that kind of classic what people think of as revenge porn, angry ex uses a photo get back at someone, is actually a fairly small number of cases. There’s a lot of cases where this is a product of hacking someone’s computer or obtaining this because you’re a telephone technician who’s got access to someone’s intimate self-portraits.

So, I think one of the points of contention that I’ve had with the ACLU and others is how to define this because there are attempts to try to say it should only be the kinds of situations where someone was acting out of personal vengeance. Whereas those of us who work on the advocacy side of these things, I know it should really be any nonconsensual use of someone’s intimate images.

Nadine Strossen: Would that be your preferred terminology, Mary Anne?

Mary Anne Franks: Nonconsensual pornography, yes.

Nadine Strossen: But you would still keep the word porn?

Mary Anne Franks: I will say this is another interesting detour to say. We actually, as an organization, I’m the president and the legislative and tech policy director of the cyber civil rights initiative, and our terminology originally was nonconsensual pornography, and we still use it because I think it does encapsulate things fairly quickly. But we have shifted to say, “Nonconsensual distributed intimate imagery,” to keep the word pornography out because many people who have experienced this abuse have objected to the term because they feel that some sort of moral judgment is being made about them.

Nadine Strossen: May I just say one thing?

Nico Perrino: Yeah, of course.

Nadine Strossen: Because it goes back to the really interesting question of terminology and the different associations with the word pornography. I recently read, and you may know the details, Mary Anne, that those who are active in combating what is typically called child pornography have also adopted a different term.

Mary Anne Franks: Yes.

Nadine Strossen: Do you remember? It’s something to do with exploitations.

Mary Anne Franks: So, there are two. Those that work in this space are actually quite adamant that child pornography is the wrong term, although it is the term that’s used in the statutes. So, child sexual abuse material, CSAM, is one definition. The other is child sexual exploitation material, CSEM. And there’s a little bit of debate about which one of those is preferred. I think CSEM is starting to win out, but definitely there is a very strong move away from the term child pornography.

Nadine Strossen: Those terminologies I find very appealing from a First Amendment perspective, which is why I first said this is the complete roster of unprotected expression, and then I quickly corrected myself. The reason being that these definitions are emphasizing that what is that issue is not only the content, you see a picture of a naked person and you say therefore it’s immoral, it’s obscene, it’s pornographic, but you were looking at it in its context; how was it created, for what purpose is it being used, what are the specific harms that it is causing other than the, “I don’t like the content,” objection to it.

So, I find that very consistent with the bedrock First Amendment principle of viewpoint neutrality where the obscenity exception is the only exception that the supreme court still countenances to First Amendment protection based only on community objection to the content without any regard for how it was created or what its actual impact is.

Nico Perrino: So, I think it was maybe a decade ago there was that famous hacking and leak of a sexually explicit images of a number of celebrities. I think Jennifer Lawrence was one of them, Scarlett Johannsson was another one of them. Presumably you have no constitutional right to hack other people’s phones or computers and distribute that sort of imagery, obviously nonconsensual, but is there anything beyond kind of the hacking or lack of permission to distribute these images that would render it unconstitutional? Or is it, as you say Nadine, we’re talking about the act that was used to make it happen?

Nadine Strossen: To me, the intrusion on privacy is profound. And Mary Anne and I have discussed this together with Bob Corn-Revere most recently and Floyd Abrams, and I think I was taking a somewhat of a different perspective from my two colleagues in that regard and perhaps from some ACLU affiliates. Because one of the statutes that I read, I think it was from Minnesota, my home state, I agreed with the court that that was consistent with the First Amendment. You told me that the ACLU there opposed it.

But I think that reasonable civil libertarians can disagree. Certainly that’s been my experience within the ACLU when you have two fundamental rights, both privacy and free speech, and gender equality, that are intentioned with each other. Different people who respect all of those rights might draw the line differently. And I guess one of the bones of contention, you’ve thought about these statutes infinitely more than I have Mary Anne, is does there have to be a specific intent, should there have to be a specific intent on the part of the person who is distributing it, what should you have to show in terms of the adverse impact.

Nico Perrino: I think about kind of the free press jurisprudence. So, let’s say material is gained and reported on that was hacked. So long as the journalistic institution didn’t do the hacking, it can report on it, right?

Nadine Strossen: Again, there have been a series of supreme court cases where, and again, these pit privacy against free speech, because those who are arguing that there should not be distribution or there should be punishment for distribution actually they say not only are my privacy interests being violated, but they actually, with support from some of the justices, have said there are actually countervailing free speech concerns. Because if you were aware that your communication could be intercepted or this information could be distributed without your consent, that’s going to exert a chilling impact on your speech.

So far in all of these cases, there have been about a half a dozen, the supreme court has consistently upheld the right to distribute the information by somebody who obtained it innocently. But in every single one of those cases, it has stressed we are making ad hoc judgments based on the particular importance of the information in each situation and the importance of the countervailing considerations. And the court has refused to adopt a categorical rule that an innocent distributor is always going to be protected.

Nico Perrino: But yeah, in a lot of those cases you’re talking about, for example Edwards Snowden’s release of information about what he argued is privacy violations, or our privacy violations, or the wiki leaks releases, here if we’re talking about explicit images of celebrities, the interest there is purely prurient, one might suspect. So, there seems to be a difference, but that difference then rests on the content itself and not necessarily the mechanism.

Nadine Strossen: Well, I don’t know if this is the point you’re making, Nico, but the supreme court in the Snowden type cases has emphasized, in pentagon papers has emphasized, the public importance of the information, that it has to do with issue of public policy. I don’t know that one could say there’s such a great public interest in seeing naked photographs of a celebrity. So, that would cut against the First Amendment claim.

Nico Perrino: Professor Franks, I see you’re writing some stuff down over there. Do you have anything to add?

Mary Anne Franks: So, this is exactly in the weeds of where the challenges are for trying to create legislation on things like nonconsensual pornography, because of all of these you could say there are some loop holes or there are some unaddressed areas in the supreme court jurisprudence so far. And when my organization wrote amicus briefs defending these laws where they were challenged on First Amendment grounds, we very much emphasized the nature or the importance of the lack of legitimate public concern in these images.

So, to your point about if someone is hacking and they’re distributing these photos, can’t we just say the problem there is hacking? And there are already laws that deal with computer hacking. And indeed if you can prove that someone hacked someone else’s accounts, then that is something that you could charge them with independent of what the information was.

But my point in writing model legislation on nonconsensual pornography and defending the laws in the states that have been challenged is to say regardless of how it was obtained. So, even if it were the ex-boyfriend gets it completely consensually, because at the time he is boyfriend, and then he distributes it. There’s no hacking, there’s no prior criminal act that we can say it is part of. Or let’s say that ex-boyfriend turns that over to a revenge porn site or to a random person online who thinks he can get, I don’t know, bitcoin for it or can get some social validation for distributing it. The argument we have is to say all of those people are doing something wrong and it doesn’t matter if they were participating in the initial illegality of obtaining the material, and there may not have been any illegality in the consensual sharing to being with.

The point is really let’s say for instance that someone found a bunch of social security numbers by fraud or through hacking. Reporter wants to talk about the leak. Well, the reporter should not then display those social security numbers. You can talk about the story, you can talk about why it matters, but you wouldn’t actually take the private information and then distribute it. And our argument is the same here to say that regardless of whether there was a good reason, bad reason, whatever the reason was that you obtained this information, you are not entitled under the First Amendment or anything else to share that private information without a person’s consent.

Nico Perrino: So, we’re talking now about nonconsensual pornography and the legal murkiness surrounding it. I want to back up and pivot a little bit to your book here, Nadine, and talk about its origins. Because your book doesn’t really address nonconsensual pornography. I think there might be a few mentions of it here or there, but generally it’s about individuals who have a problem with just pornography as expression or content, whatever you want to describe it. This is kind of going back to our, I don’t know, uneasiness with sex in America.

Nadine Strossen: Right. To the best of my knowledge, the nonconsensual pornography concept is fairly recent, certainly long after the book was originally written and published in the early 1990s. And the reason that I was asked to write the book was we had just wailing debates about what was called pornography, which was being attacked from both ends of the political spectrum very vigorously.

I already mentioned from the left end of the political spectrum and the so-called radical feminists who, for feminist reasons concerns about women’s safety and dignity and equality, wanted to suppress a category of sexual expression that wasn’t touched by the obscenity exception, as I explained. The gravamen of obscenity is that it is patently offensive according to the morass of the local community, immoral according to the local community standards. Whereas the kind of the harm that the feminist pro censorship advocates were concerned about was expression that is demeaning or degrading to women.

On the other end of the political spectrum, you had culture, religious, and political conservatives who were very much in the ascendency under Ronald Reagan; Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum, Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, Attorney General Ed Meese under President Ronald spearheaded a so-called Meese Pornography commission, which called for the censorship of sexual expression that they saw as undermining the traditional American family.

So, you had people who had very different views about which sexual expression was positive and which was negative. Because the feminists, they were not defending the traditional American family to the contrary from the perspective of the right wing, and yet they made common cost in supporting various legislative initiatives to outlaw a wide range of sexual expression, including legislation that was seriously considered at the national level did get passed in a couple of localities.

Nico Perrino: So, Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon, for example, worked with local government in Indianapolis, for example, to pass this law. Let’s talk a little bit about Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon.

Catharine MacKinnon is a feminist law professor from the University of Michigan. She argued, if I’m not mistaken, the first sexual harassment case at the supreme court, won that case. And the other feminist who was very much advocating this sort of pressive liberal perspective on pornography was Andrea Dworkin, herself a feminist writer. She wrote the book, “Pornography: Men Possessing Women,” in 1981, and she unfortunately passed away in 2005. You briefly described their main arguments.

I want to quote something form MacKinnon here. She writes, “Pornography in the feminist view is a form of forced sex in institution of gender inequality. Pornography with the rape and prostitution in which it participates institutionalizes the sexuality of male supremacy.” Needless to say, for anyone who reads your book, Nadine, you don’t agree with them, but I’d love to hear what you have to say, Professor Franks. How do you look at their arguments in your work?

Mary Anne Franks: These things are really connected, I think. When Nadine says nonconsensual pornography is a relatively new phenomenon, I would suggest that the terminology is, but part of what Dworkin and MacKinnon were getting at was that nonconsensual and coercive natures, or coercive dimensions for pornography, has always been around, and that was their focus, in fact. Now I want to clarify that I think, at least for MacKinnon, consent was less of the issue because she finds that consent is too formalistic and it’s not a capacious enough concept to make pornography okay. I don’t think she necessarily believes that there’s something like consensual pornography.

But if we think about the very first issue of Playboy, it used pictures of Marilyn Monroe that she had taken when she was basically a nobody, when she was trying to break into stardom, and she had hoped that no one would ever find these photos. She never wanted to have them out there. And Hugh Hefner purchased them and decided to use them without her consent. So, I would say actually the beginning of the most mainstream pornographic publication that it states was actually nonconsensual pornography.

And then you get even more malicious versions of this in Hustler Magazine in the 80s where Hustler is running these features called Beaver Hunt and they’re asking for their readers to submit photos of their girlfriends, of whoever the case may be. And no one really asks or cares about where did you get these photos, is the person depicted in them actually consenting. The entire kind of genre of amateur porn basically just didn’t talk about whether or not the women, and they were almost always women, whether they actually consented to being depicted in that way.

So, I would suggest that it’s always been a question of is this pornography consensual? Did this depiction happen because this person decided they wanted to be depicted this way? And if the answer is no, it’s not just a moralistic objection or a feminist objection, it is to say we care about privacy. We care about exploitation. We care about the idea that if you’re going to have sexually explicit content, everyone should be an adult and everybody should be consenting.

So, I think that’s why it’s important to think about the larger cultural examination that I think MacKinnon and Dworkin really sparked, which was are we so sure that this is in fact voluntary sexual depictions? And to point out that the ordinance was not a criminal ordinance, it was a civil ordinance that allowed women to sue if they were harmed. And not just women. They also said that it was not gender specific, although there was some confusion about that.

But I do think that’s what’s so important about that larger conversation to say when people say porn, they really do assume that it’s voluntary. They assume that something about this is liberation or expressive or whatever the case may be. And that one kind of objection is certainly, “We don’t like sex,” or, “We’re being puritan,” or what have you.

But another objection, and I think it’s much closer to what Mackinnon and Dworkin were getting at was we’re not sure that this is in fact, in any significant sense, an autonomous expression, and we’re not sure that this contributes to women’s liberation. In fact, we might think that it actually constrains their liberation and makes it hard for women to be taken seriously as equal citizens.

Nico Perrino: Correct me if I’m wrong. My understanding from reading MacKinnon and Dworkin is that they didn’t see that any pornography could be consensual because of the kind of structural make up of society, and therefore it all should be banned. Is that right, Nadine?

Nadine Strossen: Yes.

Nico Perrino: So, theoretically, speaking to Professor Frank’s point, you could set up a legal framework, and we have some of those, to determine whether the pornography was consensual or not. But to just ban it outright and say that nobody can consent to it is a different argument and a bit broader.

Nadine Strossen: I mean, I could not stress more strongly that of course as an advocate of civil liberties and human rights, of course I oppose any exploitation of any human being, including through fraud and deception, as well as through more overt forms of coercion such as violence. Unfortunately, we have exploitation, subtle and extreme, in every profession, not only sex work, but dare I say in academia, in the legal profession, even among the judiciary, the military, the priests, you name it. And so, the goal is to make sure that everybody who participates is doing so in a voluntary, consensual way.

Now, I understand that all of us face constraints, and I do address this in the book. To some extent we can say well, somebody who chooses to earn a living in various ways, whether it be as a house cleaner or a pornography performer, or for that matter an accountant or a lawyer, is doing so in order to make a living, is doing so consistent with educational opportunities, limited educational opportunities. And I expressly say in the book consistent with not only women’s rights but human rights, we have an obligation as a society to provide the educational and financial and, in these days, technological resources to give maximum freedom of choice to every human being in how they use their bodies and how they earn their living.

Where I part company with MacKinnon and Dworkin are their many expressed statements, including in the legislation itself, that there is no consent, and they have a long list in the legislation of what will not be evidence of consent, including a signed contact, including an affirmative statement, “I am voluntarily doing this.” And in fact, MacKinnon, and I quote her in the book, I want people to know this is not hyperbolic paraphrasing or distortion, you can look up her own sentence, she literally equates women with children as being inherently incapable of consent, not only in performing for sexual productions, but also in having sexual relations in general. There is this notion that given our patriarchal structure, women who think we are consenting to sex, let alone enjoying it, are victims of false consciousness. And to me, that not only does not promote women’s equality and dignity but is actually deeply inconsistent with it.

Nico Perrino: And Professor Franks, do you take issue with that conception that Dworkin had separate from the consent discussion, the legal definition of consent that we were talking about earlier? Do you agree that the structures in society are such that women can’t consent to pornography?

Mary Anne Franks: It is such an odd proposition in some ways to say what does it mean to consent to pornography. I will say that my own concern here is to say that if we’re looking at a world where on the one hand you have the kind of radical feminist critique that says there’s no such thing as consent as valid or legitimate to pornography, and then you have the kind of view that pornography is liberating, that it is uncomplicated, let’s say that that’s the view that most people who are actually involved in the business of producing pornography and selling pornography, this view they have, I would say that neither one of those extremes is where we should end up. And the place where we should have some overlapping consensus, and I think sometimes we have, is to say that the extent that there may be ambiguities on either side. The one overlapping consensus should be if there isn’t consent, and we can actually show that there is not consent in any conventional sense, that should be impermissible.

And I think the interesting place there though is to say that once you start looking at whether or not something was consented to, you then start to realize that the concept of consent is very fraught. And you can see why it is that MacKinnon and Dworkin would say a signed contract by itself is not evidence of that. We think of that.

And I think many progressives would agree that that’s true when we talk about exploitative employment contracts. Sometimes you sign things, and that’s not a sign that you actually consented in an informed and robust sense. Sometimes that is the workings of a pretty vicious capitalistic system that is trying very hard to get you to sign away rights and dignities that maybe you should not.

So, I do think that the power of their critiques still exists to say, “Are you sure this is consent?” Would I go as far as to say there’s no such thing as consent to pornography if pornography means merely sexually explicit content? No, I don’t think that’s true.

Nadine Strossen: May I respond?

Nico Perrino: Of course.

Nadine Strossen: And I agree with everything Mary Anne just said. I’d like to respond to another point she raised, which is an important one. And that is that somehow we should be less concerned about the speech suppressive impact of the Dworkin/ MacKinnon style of legislation because it’s civil rather than criminal. And the answer to that comes from the supreme court.

Nico Perrino: And can you describe what it means to be civil versus criminal? We have lay listeners here.

Nadine Strossen: Yes, I’m so sorry. That means that rather than a government employed prosecutor prosecuting you for a crime, the punishment for which could even be imprisonment as well as a fine, you have another citizen, in this case it would be a women, or as Mary Anne says it could be a man, who says, “I was harmed by this pornographic production,” bringing you to court and suing you for damages, the monetary damages, that allegedly flow from your production of pornography.

So, what the supreme court sensibly has said in constructing the First Amendment, which is Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech, it has interpreted the term abridgment sensibly in a very functional, practical way. Is the measure that you are challenging likely to have a speech suppressive impact? And in a very, very famous case that did involve a civil damages action rather than government prosecution, New York Times versus Sullivan, which was a toward action for defamation being brought against the New York Times seeking hundreds of thousands of dollars of damages at a time when that was worth a lot more, it’s worth a lot more than today, the supreme court said, “This is subject to First Amendment constraints.”

In fact, the criminal fine that was available for criminal prosecution for liable was 1/1,000th of the amount of damages that could be imposed in a civil action. And so, the New York Times and others would be even more deterred by the fear of a civil lawsuit than by the fear of a criminal prosecution. Therefore, the First Amendment is implicated and violated.

Nico Perrino: Yeah. And I think folks might remember that law that was passed in Florida a few years ago, that “Don’t say gay,” law that also created a civil cause of action if it was violated. And I believe, although correct me if I’m wrong, Nadine, if you recall some of the big tech legislation we’re seeing like the Net Choice cases might have created a civil cause of action for users to go after these tech platforms.

Nadine Strossen: Exactly. Think of yourself, if you are writing anything or producing any images with sexual content to expose yourself to a potential lawsuit by anybody who says, “I’m harmed,” even if you ultimately win the lawsuit, it is still so burdensome financially and psychologically that the courts, and I should say there were two courts that ruled on this model three courts that ruled on this model legislation I’m so sorry , it’s four because the U.S. supreme courts summarily affirmed, it didn’t even hear oral arguments or receive briefs. They thought that the First Amendment violation was so severe. So, really the only, to the best of my knowledge, written opinion came interestingly enough from a female federal court judge in Indiana who said that the whole definition and the whole approach just squarely violates the First Amendment because of this enormous deterrent chilling effect.

Nico Perrino: I should, keeping our listeners in mind, step back here a little back and talk about that model legislation. We’ve referenced it a number of times. And I don’t have the whole piece of model legislation in front of me, but I have what I think are the operative parts. It says that porn is a form of sex discrimination, and it defines porn as graphic sexually explicit subordination of women and/or words, and it kind of creates four causes of action if I’m not mistaken. It says you can bring a civil claim if someone is coerced into pornography. Pornography is forced on a person. You can bring cause of action if there’s assault of a physical attack due to pornography. And then the last one is trafficking in pornography. Nadine, I’d imagine you are okay with some of those.

Nadine Strossen: No, not really, for the same reason that the judge found the whole statute unconstitutional, and that is the overly broad, inherently subjective definition which endangers essentially all sexual expression. And it’s words as well as pictures. And then in my book I go through and explain some of the additional problems with each of those concepts. I suppose one might be able to rewrite some of the elements in ways that would be sufficiently narrow.

This is a thought experiment now, Nico. I don’t think anybody should be subject to harassment through having any kind of expressive content forced upon them. That said, the statute was written so broadly that it was inconsistent with supreme court decisions that in fact had struck down state statues that outlawed the mailing of certain sexually related materials such as information about contraception. That was outlawed as I recall.

In an old case the supreme court said, “Well, it’s not such a big deal to have to make the trip from your mail box to the garbage can. So, that’s not such an imposition on privacy.” And the definition is written so broadly that there’s a lot of important information about sex that is going to be deterred. So, the devil is in the details, and the details in every single one of these statutory elements was inconsistent with any freedom for any sexually seemed expression, including pro feminist material.

That was part of the reason why I teamed up with other feminists, advocates, writers, lawyers, human rights crusaders, in two organizations. One was called the Feminist Anti-Censorship Task Force, one was called Feminists for Free Expression. And we made arguments that these model laws not only violated very important fundamental free speech First Amendments norms, but also were inconsistent with gender equality with women’s rights.

And that argument was made, by the way, by the ACLU women’s rights project, which was then headed by its founder, Ruth Bader Ginsberg. That along the predictable causalities of this kind of broad language would be writings of special importance to women and feminists, including material about contraception, about abortion, reproductive freedom, LGBT sexuality. And when the law was enacted in Canada, in fact it was exactly that kind of expression that was immediately targeted.

Nico Perrino: And I do want to get to what happened in Canada here in a second, but I also want to give Professor Franks a chance to pine on Dworkin and MacKinnon’s model legislation. I will kind of ask you the flip side of the question I asked Nadine. Presumably you would think that the one kind of cause of action they were trafficking in pornography is too broad. The other ones speak to the coercive aspects that can sometimes be at play, and expression, we’re talking about pornography. But that just means essentially all porn is sex discrimination, right?

Mary Anne Franks: It depends. Again, they have a very specific definition of what porn is. So, they’re saying that you have to depict a woman or a man or whoever the case may be as enjoying their subjugation, then I think that they would be comfortable saying that that is what is off limits. Although, my point in raising before this civil

Nico Perrino: And that can be consensual.

Mary Anne Franks: Exactly. So, the idea that you wouldn’t be able to present some kind of S&M relationship that was voluntary or some kind of eroticization of subordination, all of that would somehow be off limits. But I do think it is important, I mean Nadine is of course right to say that the civil versus criminal distinction is not one that gets you out of First Amendment trouble, nor should it, but the point being I think it’s not accurate to say this ordinance outlawed pornography. It did not because nothing in civil law really outlaws something.

It creates, as Nadine says, maybe a chilling effect. People have to worry that they might get sued. We don’t always think of that possibility as being a bad one. I mean, that is the reason why we have any number of really open-ended tortes is because we are trying to create something like an incentive for people to be careful about what it is that they say in case they harm someone. So, people can still get sued for defamation, and personal figures can be responsible for saying hyperbolic things about another person. That’s chilling in some ways, but it’s an attempt to balance the concern about freedom of expression with the damage of someone’s reputation.

And going back to the Hudnut decision, which is the decision that deals with the ordinance that came out of the seventh circuit that the supreme court did summarily affirm, I think it’s really, really important to note that the reason why judge Easterbrook said this cannot past First Amendment scrutiny is not because he thought the empirical claims first of all were not true. He says, “I think everything that MacKinnon and Dworkin are saying about how pornographic depictions make it harder for women to be treated with respect and harder for them to survive in society.” He says, “I think all of these things are true.” And then he says

Nadine Strossen: I disagree with that.

Mary Anne Franks: But then he says, “And the reason why we’re going to say that this ordinance is failing is precisely because they’re right, or I’m going to assume that they’re right.” That is because of a viewpoint, right. It specifically says, “Showing women enjoying subjugation,” and Easterbrook says, “That’s classic viewpoint discrimination. That’s exactly the power of the ordinance. It’s what makes it so fatally flawed when it comes to the First Amendment.”

But what he says then is, “If only they had written this in terms of obscenity.” So, back to what Nadine was saying, and she and I agree on this part, that obscenity is a really strange category to retain as a First Amendment exception because it is so dependent on the morality of prevailing views. So, it’s what is patently offensive to the community.

But Easterbrook says, “Have they only talked about the offensiveness to the community, this might have worked.” In order words, when he rejects what they’re saying, there is actual harm to women here. He says, “If only you had invoked an abstract harm to the society, to moral sensibilities, you would be okay.” That to me really exposes the kind of really unsettling nature of the First Amendment and how it works here. Because it’s not saying you can’t regulate this kind of expression, it’s saying you would have been able to do so had you phrased this as an offense to the community, not in terms of actual harm to women.

And that’s pretty disturbing because it’s saying essentially that the First Amendment doesn’t care about harm, it only cares about morality. Which I think MacKinnon was very clear all throughout the process where they were developing that ordinance to say, “We don’t believe in morality because morality is a patriarchal construct. We’re not after moral concerns. We’re after actual harms.” Which is why this is a civil ordinance which requires you as the plaintiff to show harm. You can’t just show up in court and say, “You hurt me,” and that’s the end of it.

So, I do think that it’s worth emphasizing that, yes, civil ordinances can also be chilling in terms of free speech, but they are also not just simply coming out and prohibiting pornography full stop. And that is not something the ordinance could have done.

Nadine Strossen: Two points: number one, I think you misspoke, Mary Anne, and corrected yourself, but I want to be sure about this that Easterbrook did not reach a conclusion. By the way, he was the author of the seventh circuit court of appeals decision affirming the trial court decision that this law violated the first amendment. And he did not say that he agreed or that evidence showed and persuaded him that pornography is defined by the ordinance caused harm. He said, “I will assume for the sake of argument that it does cause the harm.” Even so, or especially so, that is diametrically inconsistent with the viewpoint neutrality requirement of the First Amendment, and that’s a typical move that all judges make.

For example, when the ACLU successfully challenged the communications decency act, which outlaws a patently offensive and indecent expression online, the court said, “We’re not reaching the question of whether it actually causes harm,” which was the rationale for the legislation. Because even assuming for the sake of the argument it did, it still violates the First Amendment by being overbroad and so forth.

The second point I want to make, and I do stress this in the book, is one really important point of agreement among all feminists, to the best of my knowledge, including MacKinnon and Dworkin and yours truly and the organizations I mentioned, is opposing the obscenity exception. And I think the problem, Mary Anne, is that we still have an obscenity exception. I think it is completely inconsistent with First Amendment values to allow government to outlaw or suppress in anyway expression solely because it is inconsistent with the morals of the majority. That is squarely inconsistent with what the supreme court has called the bedrock principle underlying the first amendment of viewpoint neutrality.

And the reason we have this anomaly is that the supreme court has not revisited the obscenity exception which it created in 1957 out of whole cloth. It has not been revisited it since 1973 when four out of the nine justices, including the one who had created the exception in the first place, Justice Brennon, wanted to overturn it. And since then, many individual supreme court justices have said we’ve got to get rid of this exception, but they have never gone back to revisit it.

Meanwhile, in every other area of First Amendment law, the supreme court has consistently and strongly enforced the viewpoint neutrality principle so that previous categories of speech that were unprotected because of disapproval, societal disproval, of their content have gradually been brought within the Frist Amendment fold, including commercial speech and defamation and profanity and fighting words, you name it. So, the obscenity exception is more and more aberrant to First Amendment principle.

Nico Perrino: But is it a dead letter in practice?

Nadine Strossen: That’s a really good question. I can’t say I’m an expert on it, Nico, but for the episodic articles I read about it, it seems as if there are Mary Anne, you may know more about this, but apparently there are I’ve read that there are many fewer prosecutions, even when we’ve had a couple recent presidential administrations that have pledged to increase obscenity and enforce it at the behest of certain other constituents. I think George W. Bush did that under Attorney General John Ashcroft.

But as I understand it, it never really materialized except in increasing the enforcement of the child sexual abuse materials, otherwise known as child pornography laws, which I think is completely appropriate. But I’ve read that it has become increasingly difficult to get a jury to convict, even in jurisdictions that used to be considered very conservative and very favorable for bringing these prosecutions, that apparently people have become more tolerant towards sexual expression and less likely to convict.

Nico Perrino: Let’s turn now to Canada. You mentioned that the model legislation was adopted in Canada. There was also I guess the supreme court ruling, a Canadian supreme court decision, in the case Butler v. The Queen where some of MacKinnon and Dworkin’s thoughts and philosophies and thinking surrounding pornography were actually adopted. And I guess in the Canadian supreme court case, they adopted the bad tendency tests. What were the effects of this in Canada, and is that still the case in Canada?

Nadine Strossen: So, just to be very precise on the details, there wasn’t a statute that was adopted. It was the Canadian supreme court in the 1992 Butler decision incorporated the feminist MacKinnon concept of illegal pornography into Canada’s preexisting obscenity statute. So, rather than using the traditional definition, which we still have in the United States of basically immoral patently offensive material, it was material that is demeaning or degrading to women.

And the immediate result was the suppression of feminist works and LGBTQ+ works, including seizure at the U.S./ Canada border, including works by Andrea Dworkin herself. Not surprisingly in Dworkin’s work that castigate pornography, she includes many examples of the pornography that she believes to be dangerous. But as I show in the book, she also writes very explicitly novels that describe scenes of sexual degradation and torture. So, that was the basis for seizing her novels.

And the feminists and gay book stores in Canada, which at the time were not too numerous, were all subject to investigation and prosecution. And Mary Anne, you earlier said that pornography is mostly imagery, but in the Canadian situation, as I’m sure you know, the number of the prosecutions and the seizures were completely of text with no pictures whatsoever.

And you actually had a judge in one of these cases, it was I think the earliest case under Butler, involved LGBTQ/ feminist book store, LGBTQ lesbian magazine, with a story about two women who have sex which initially is not voluntary and then it becomes consensual. And when that was raised as a defense, this story could not possibly be demeaning or subordinating. The judge was literally quoted as saying, “The fact that a woman would agree to this kind of sexual contact with another woman makes it even especially demeaning or degrading.”

Now I had the opportunity to debate Kathleen Mahoney, who was the Canadian feminist lawyer who spearheaded this interpretation and argued the case before the Canadian supreme court, and I quoted all of this material, the information that I’ve now summarized, and she said, “Well, what do you expect? Of course the judges and the prosecutors and the police officers were discriminatory against women and against lesbians.” Well, for me that’s exactly the reason why you do not turn over to them this tool that is inherently subjective and discretionary. One person’s degradation is somebody else’s liberation.

Nico Perrino: The continuing relevance of this discussion, your book, Nadine, was written in 1995. The best data I could find, and data is not easy to come by with regard to individuals, in this case Americans, who watch porn or who have watched porn, but the best data I could find suggests that roughly 6 in 10 Americans, 58%, report having watched pornography at some point in their life, including more than 1 in 4 who have watched it in the past month. Pornography has been with us since time in memorial. Is there a way to effectively regulate it or to eliminate pornography in society? Professor Franks, how do you think about it?

Mary Anne Franks: Well, I suppose the prior question is what this discussion has been getting at is would we want that to be the case? So, the first question is would we want to do that, first of all? And if we can’t figure out even what we mean by pornography, because it has such varied definitions depending on context, I think it wouldn’t be wise to want to work towards a principle of let’s get rid of this. Because clearly it has meant many things that we would think of, certainly some of us would think of as being valuable to society. And even if we don’t think it’s valuable to society, we might think that regulating is work than letting it flourish.

But I would say that I guess the larger point that I would draw from some of these excellent points that are made in books like Nadine’s are do we want to single out pornography laws for their bad affects? So, when I hear about we look at an ordinance, we look at an adoption of these kinds of views and say, “Well, it was used against these kinds of groups or these kinds of content that we think of as being valuable.” And I think well yes, but as someone who has worked on legislation for the last decade, that’s true of any law. Any law can be used in a bad way.

So, I think we need to be careful about thinking of it as too much of a slam dunk to say, “Oh, you see there was a bad application.” Well, that often happens. What I take away as a lesson from that is try to make I less possible to be misused. So, write narrower laws that don’t really on really subjective concepts. Which is one of the reasons why, again, we agree on the obscenity category as being not a good one because what does it mean to be patently offensive.

But I will say that’s where I find it frustrating to deal with some of the civil libertarian establishment that seems to think of the First Amendment and all of its doctrinal baggage as being the be all and end all because it is still giving us the obscenity exception. We are still talking about child pornography as an exception as if that weren’t some kind of viewpoint, which I would suggest it is, and rightly so. Again, it’s not just naked pictures of children. There are plenty of depictions of minors without their clothes on that will not be qualified as child sexual exploitation material. It has to be sexual conduct or lewd and lascivious displays of genitals.

Now, what does that mean? Can we imagine prosecutions using those words that are over regulatory? I think we can. And what we decided lewd or lascivious is very much a moral judgment. It’s not as clear cut as saying anything involving minors.

So, what I would think of as a much more mature free speech jurisprudence and discourse would be to say that sometimes to have a functional First Amendment or a functional free speech regime, we have to admit that sometimes harmful viewpoints, harmful expression, there is a good reason to regulate it, even if it’s possible that that’s going to create overregulation. Sometimes it’s worth it, because how else would we justify defamation or child pornography laws or fraud laws or any of the privacy exceptions that the court seems to be making? Maybe not explicitly but at least implicitly when they allow certain privacy regulations to go forward. Or labeling laws, or food and drug issues, or all the things that we think of that we think, yes, there’s some downside because any time you say, “Don’t say this word,” or, “You can’t use this term,” there’s always going to be some danger chilling.

But if we could just be confrontational about how we are willing to say as a society sometimes there is expression that is so harmful that we think it is better to try to regulate it rather than to simply let it flourish. We’re doing that already. We’ve always done that. There’s never been a moment in U.S. history, or I think in any society, where all speech has been protected all the time. There’s always been limitations. I think the only real question is how to grapple with what those limitations and to make sure that they’re principled and that they’re sound and that they’re not subject to eh vagaries of social morality.

Nadine Strossen: I basically agree with that, but I think where I would disagree with the greatest respect, Mary Anne, is on the extent to which harm, cognizable, punishable, regulable harm can be defined solely in terms of viewpoint. And I add the word solely because viewpoint is an element, but as I analyze and understand, and in my own mind justify, the appropriate limitations on free speech and by the way, I wouldn’t see them as exceptions to free speech. I would see freedom of speech has a limited scope.

And the protection is that government may never regulate or restrict speech solely because of objections to dislike of or general fear of its potential harm. That rather you have to look not only at the viewpoint or content, but also whether in context, in particular facts and circumstances, the speech directly causes or imminently threatens certain specific serious harms that are independent of objection to its viewpoint.

And that’s the way I understand every single one of the existing exceptions, or I should say limitations on free speech, and why I bristle at any concept such as obscenity, which is not even trying to find any harm other than to the mind of the beholder. And so-called child pornography or child sexual abuse material, I think the supreme court underscored the concept I’m trying to articulate when it rejected concepts of virtual child pornography, which looked indistinguishable from actual images of actual children.

So, presumably if you’re focused on the harm that is reflected by the viewpoint by the depiction and the potential impact it has on the mind of the beholder, the two are indistinguishable, and virtually every lower court judge who ruled on that statute upheld it. But the supreme court struck it down strongly insisting that there is a tangible, demonstrable harm here that has nothing to do with the viewpoint or depiction or its impact on the mind of the beholder. But we’re only concerned with was there an actual child actually harmed.

Nico Perrino: I’m going to wrap up here in a second, but I want to talk about one of the highest profile controversies surrounding pornography at the moment, at least in higher ed. It involved the former chancellor at the University of Wisconsin La Crosse, Joe Gow, also a tenured professor. It turns out he and his wife have an Only Fans account called Sexy Happy Couple in which they do porn. Joe Gow decided that he was going to retire recently, and so he also decided that he was going to be public he had not retired yet, but he decided that he was going to be public with his pornography channel. University of Wisconsin La Crosse and kind of the wider University of Wisconsin system didn’t like this. They fired him in his position as a chancellor, the argument being that he’s kind of a public representative of the university. And he is going through proceedings right now to revoke his tenure ship.

And some of the allegations, at least as I understand them, seem to be deminimus. They’re just searching for something to go after him about; the fact that he used a university laptop to perhaps purchase something that he used in the course of his pornography. I’m sure college and university professors use their work laptop to buy things on Amazon or anything anywhere else all the time.

And when talking with family or friends in Wisconsin, it seems like the response form the average citizen is that a chancellor and a professor shouldn’t be engaged in porn. It just comes down to that. There’s something about porn. And it made me reflect as I was reading your book, Nadine, on this quote from Susan Sontag. “Since Christianity concentrated on sexual behaviors as the root of virtue, everything pertaining to sex has been a special case in our culture provoking peculiarly inconsistent attitudes.”

So, I want to get your guys’ thoughts on the Joe Gow situation because it’s one of those things that breaks through the First Amendment walls that are often built around these discussions. And you hear it talked about on the Today Show, for example, as one of those dog bites man stories. But also by way of closing, just reflect more broadly on the role of sex in American society, going back to our kind of Protestant origins. There just seems to be something unique about it.

So, let’s start with you, Professor Franks. I’d love to get your thoughts on this case, and then we’ll close with the author.

Mary Anne Franks: It’s a really interesting case because when you said the part about how there are so many people who have this kind of instinctual reaction that this is not what a professor should do, I think of Nadine describing that kind of mind of beholder, that kind of instinctual, reactive kind of, “Oh, that’s immoral,” or, “There’s something just wrong with this because it’s too explicit or it’s sexual,” or what have you.

And I don’t share that response because what I wish that was the response people had when they found out the professor has a history of domestic violence or sexual abuse. If people are going to have those kind of moral reactionary judgments, I wish it weren’t about what I from all I’ve understood about his case, and I could be missing something, but it seems to be consensual, fairly healthy, really kind of open and affirmative sexually explicit content that he is producing.

Nico Perrino: With his wife.

Mary Anne Franks: With his wife, right. And so again, this is not as far as, again, I understand it, there are books, there are movies, there are channels, I think they cook naked together. It’s this extremely wholesome sort of and it seems that the only thing that bothers people is the idea that they might be naked when they’re doing it, and that seems like a very strange response. When I think about where I spend most of my legislative and policy time, which is thinking about sexual exploitation and abuse and negative stereotypes about women and about the LGBTQ community, I think this by contrast seems refreshing to me. So, I don’t understand that kind of reaction.

And I do think that just to tie some of these ends together, that Nadine says that viewpoint alone seems like a not good enough reason to regulate something, I think I agree with that, especially if we’re talking about that kind of, “Well, I wouldn’t do that,” or, “I don’t think that’s proper.” That should never be a good enough reason or a sufficient reason to regulate something.

But I do hope that the ACLU is listening to you because that seems to be the position they have taken. When it comes to their fights against nonconsensual pornography laws, the fight, to be clear, is that they’re saying those laws should only be restricted to people who are try8ng to exact vengeance on their partners, which I would say is a viewpoint, and that’s a bad road to go down. It’s not because you’re trying to humiliate your ex. It’s because you are violating someone’s policy. It shouldn’t be about the motives.

So, I think the ACLU has gotten itself a bit confused on which perspective it should have on I think Nadine’s more, for me at least, sophisticated understanding of how viewpoint is actually not the safest place to land if we’re going to regulate something. And we do want some kind of objective as much as we can get there.

Harm, we do want some kind of proof that you can’t just say you’re offending by something or that something seems corrosive to morals, but rather you can spell it out. And we should be able to do that. We can do that in the nonconsensual pornography context. We can say women lose jobs, they have to leave their homes, they get stalked, they get harassed, they get suicidal. There’s all these ways that we can actually show. It’s not just about a viewpoint, and in fact it doesn’t matter what the viewpoint is, it matters that there’s harm. So, on that I think that’s the safest place to land and make sure that harm is actually a robust and explicitly expressed concept.

Nico Perrino: Nadine?

Nadine Strossen: Well, in defense of my ACLU colleagues, I have to say I simply don’t know what the position is of various ACLU, as we call them, affiliates. Each state has at least one affiliate, and they not unusually are taking different positions from each other.

Now, on the broader issue that’s raised here, it makes me think of an early point that I believe you made, Nico, that Catharine MacKinnon, in addition to spearheading a concept of illegal pornography that I consider to be inconsistent with not only free speech but also women’s equality and dignity, also spearheaded the concept of illegal sexual harassment that constitutes illegal sex discrimination. And that was an enormously positive contribution, and I want to solute her for that as I do in the book.

That said, while the concept is positive, it has been enforced in ways that have been negative, as FIRE well knows, a speech suppressive way because of the false equation of conduct that is discriminatory on the basis of sex or gender has been too often falsely equated with expression that is sexual in nature, or sexually suggestive in nature. And so we have seen so many cases on campus of any sexually themed expression, including in art or literature or even health and science and medical classes, where the mere fact that it is about sexuality has led to complaints of sexual harassment, including against female feminist professors.

So, I would say that there is a and I’m so glad that Mary Anne and I are on the same page at least with respect to this particular example, that somehow sex itself is seen as being dangerous and harmful completely independent of any concrete, tangible, demonstrable harm at all, let alone any harm to women in particular. So, by all means, let us pursue enthusiastically and vigorously our common goals of freedom and equality and robust freedom of choice, robust consent for every person. Let’s try to craft very targeted measures that are not overly vague, overly broad, do not give too much discretion to the enforcing authority, but will promote common concerns about safety and consent consistent with free speech.

Nico Perrino: And for clarity, you think Professor Joe Gow should be able to have a side hobby as a pornographer and also be a professor, I’m assuming?

Nadine Strossen: Yes, I do.

Nico Perrino: All right. I think we’re going to leave it there. Nadine, I appreciate you providing the impetuous for this excellent conversation, and Professor Mary Anne Franks, I appreciate you joining us.

Mary Anne Franks: Thank you.

Nico Perrino: Nadine Strossen is an Emeriti professor at New York Law School, a senior fellow at FIRE, and the author of, “Defending Pornography: Free Speech, Sex, and the Fight for Women’s Rights.” Mary Anne Franks is a law professor at George Washington University and the author of the forthcoming book, “Fearless Speech: Breaking Free from the First Amendment.” And I hope when that book comes out in October we can discuss it as well. I suspect there will be some areas of disagreement that will be fun to unpack.

This podcast is recorded and edited by a rotating roster of my FIRE colleagues, including Aaron Reese, Chris Maltby, and Sam Niederholzer. To learn more about So to Speak, you can subscribe to our YouTube channel or our Substack page, both of which feature video versions of this conversation. We’re also on X and on Facebook where you can search for free speech talk and find us.

We take feedback at sotospeak@thefire.org. If you have feedback for me, my guests, or anything else related to the show, please send it there. And we also take reviews on Apple Podcasts, Google Play. As I say on every show, reviews help us track new listeners to the show. So, please consider leaving one. And until next time, thanks again for listening.