Table of Contents

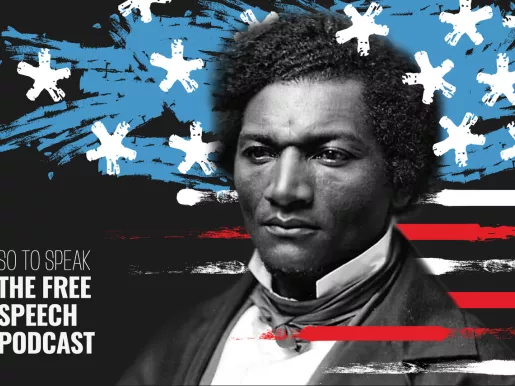

So to Speak Podcast Transcript: Free speech and Abolitionism

Note: This is an unedited rush transcript. Please check any quotations against the audio recording.

Nico Perrino: Hey folks. Welcome back. It’s Nicco here. A few weeks ago, my wife and I welcomed our second son into the world. So, I’m spending the next couple of weeks on paternity leave, hanging with my newborn, trying my best to prevent my toddler from inadvertently killing me. As a result of my leave from duty, though, I am turning the podcast back over to my colleague, Tyler MacQueen. Last year on Constitution Day, you might recall that Tyler hosted Episode 170 for us. It was called Free Speech and the American Founding. And in it, Tyler explores how the American conception of free speech came to be, looking at it from the colonial era on through to the ratification of the Bill of Rights. Now, on today’s episode, Tyler fast-forwarded a few decades to look at how 19th-century proslavery advocates in America used many forms of censorship. Sometimes, violent mob censorship to maintain their status quo.

And how as a result of this censorship, abolitionists like John Quincy Adams, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and others became some of America’s most vocal and eloquent free-speech advocates. This is a stirring, even emotional story that highlights some of the most important and tragic moments from American history. I learned a lot from it. I hope you enjoy it. Now, let’s get on to the show.

December 18, 1835, was a typical day in the United States Congress. On that day, William Jackson, Representative from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, rose on the House floor to present a petition calling for the immediate abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. Motions such as this were common among Northern politicians aiming to please their constituents back home. What we think of as the abolitionist movement really kicks off and kind of full steam in the 1830s.

And one of the forms it takes is petitions to Congress.

Tyler MacQueen: This is Damon Root, a writer at Free Think and the author of A Glorious Liberty, Fredrick Douglas and the fight for an antislavery constitution.

Damon Root: Antislavery groups, abolitionist groups, Quaker groups are sending petitions to Congress saying abolish slavery in Washington, D.C. You’re Congress. You have the power to do that. Praying for the abolition of slavery. And the rights petition the government for redress of grievances is there in the First Amendment. So, this is a constitutional right that these antislavery activists and abolitionists are exercising. So, these petitions kind of really come, start pouring into Congress in the 1830s especially. It happens before then, but that’s really hitting full stream in the 1830s.

Tyler MacQueen: But what happened on December 18, 1835, was unprecedented. An emotion never before seen on the House floor. James Henry Harrison of South Carolina moved that Jackson’s petition not be received. Embolden, several other Southern representatives stood up to second the motion. The shock and anger were immediate. And the debate over whether or not to accept the petition dragged on for five months. In the end, the petition was denied. And Congress adopted a resolution that would later become known as the Gag Rule, which prevented any abolitionist petitions from being presented or discussed on the Congress floor.

Damon Root: Congress is full of proslavery representatives. Representatives of slaveholding states who are stodgy violently proslavery. And they just have a kind of a collective freakout about these petitions. In the mid-1830s, Congress passes something. The House of Representatives and the Senate does the same, called the Gag Rule, which says that these petitions will not be received by Congress. They’re essentially sort of tabled. We’re not gonna acknowledge them. There’s gonna be no debate on them, no discussion. And the representatives and senators are gagged, are prevented from speaking about these petitions. So, this huge fight about free speech and abolishing slavery is just raging in Congress at the time. And the slaveholders their position is that these are incendiary pamphlets.

These are stirring up [inaudible] [00:04:27]. They are violating state laws, which prevent anyone but the master, the enslaver, from speaking to the slave without their permission, and they’re talking to the slaves through these. And they see it as this threat to sort of this whole social order. And in a way correctly, they kind of collectively recognize that the power of these ideas, these antislavery ideas, and their spread. And so, they’re trying to stamp them out. And so, the authority they have in Congress is to silence this debate.

Tyler MacQueen: The following year, in defiance of the Gag Rule, Representative John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts presented the House Speaker with a petition written by 22 enslaved people. With that, all hell broke loose. House Members realized that if enslaved people possessed the right to petition, which was protected in the First Amendment, what other constitutional rights did they have? It was a line of thinking that, when pondered by Southern politicians, led to a dangerous and society-altering conclusion, and Adams knew it.

Damon Root: The great John Quincy Adams, a former president of the United States, son of the former President John Adams, son of Abigail Adams, has this incredible pedigree. And this rare sort of second act in American politics where presidents normally disappear from the stage, maybe reluctantly so, but they disappear. Adams, he sticks around. He goes to Congress as a Representative for Massachusetts, and he leads the fight against the Gag Rule. And he recognizes that when you try to silence speech, what you really do is you add fuel to the speaker's fire. You provoke more speech.

And he says, “Listen, you guys, you say you don’t wanna have a discussion about slavery. That’s why you’re gagging these petitions. But what’s gonna happen? We’re gonna discuss slavery. We’re gonna be discussing these petitions. You say they’re incendiary. Well, every speech that anyone north of the Mason-Dixon line makes in Congress is gonna be an incendiary speech. And what’s gonna happen? You’re gonna have more talk about slavery.” And that’s precisely what happens.

Tyler MacQueen: In response, the Dixie-dominating government adopted a resolution stating that enslaved people did not possess the First Amendment right to petition. Years later, a man recalled hearing about the petition as a teenager while he was enslaved less than 100 miles from the nation’s capital on the Eastern shore of Maryland.

Fredrick Douglass: I will remember getting possession of a speech by John Quincy Adams made in Congress about slavery and freedom and reading it to my fellow slaves. What joy and gladness it produced to know that so great, so good of man was pleading for us. And further, to know that there was a large and growing class of people in the North called abolitionists who were moving to our freedom.

Music: Sweet low, sweet chariot.

Tyler MacQueen: This man was Frederick Douglass. In the coming years, Douglas would take his place among that class of people in the North called abolitionists. And in doing so, he would become arguably the most famous advocate for free speech in American history. Douglas's notoriety on both sides of the Atlanta coincided with the escalating conflict between abolitionists and proslavery factions at the state and federal levels. And at the heart of this debate over human freedom was the suppression of free speech and the free press.

Music: Coming forth to carry me home.

Tyler MacQueen: In the fourth decade since the adoption of the Bill of Rights, the question of what to do with American slavery had reached a frustrating stalemate. The road to abolition first proved promising with the passing of the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 and the banning of the international slave trade in 1808. But while the North had been graduating abolishing slavery since 1776, the practice was expanding in the South after the patenting of the cotton gin. With unmatched efficiency, the cotton gin could remove cotton fibers from the seeds. A tedious and painstaking task when performed by human hands. The increase in cotton production meant a greater need for labor, however, and the nation's slave population tripled as the demand for cotton exploded. The newfound wealth lauded the South into contentment, becoming less enthusiastic about the prospects of emancipation. In time, Southern states began to reject and censor all thoughts of abolition, even going so far as to impose the death penalty for the circulation of pamphlets advocating for abolition or emancipation.

Jacob Mchangama:It was typically criminalized to teach enslaved people how to read.

Tyler MacQueen: This is Jacob Mchangama, Executive Director of the Future of Free Speech Project of Vanderbilt University, senior fellow at FIRE, and the author of the book Free Speech. A history from Socrates to social media.

Jacob Mchangama:Censorship and ruthless suppression of free speech was part and [inaudible] [00:09:47] of slavery. It was one thing for in the logic of slavery to enforce censorship and suppression of the enslaved because they were your property. They were chattel, and you could do with them whatever you pleased. So, no one saw it, I think, as a suppression of free speech. White people in the North, that’s a different phenomenon, and there you see some pretty astounding instances of hypocrisy. So, you take, for instance, Virginia, which in June of 1776, had approved the first and most famous state decoration of rights, which referred that press freedom was restrained only by despotic governments. And it was also in Virginia where Madison and Jefferson had led the fight against this Sedition Act back in 1798. But then, in 1836, Virginia, and this is a good example, criminalized publications that were intent on, “Persuading persons of color to rebel or denying the right of masters to property in their slaves and inculcating the duty of resistance to such right.” So, in other words, if you circulated or wrote pamphlets or other writings in Virginia that spread the idea that slavery was evil, that it was against the laws of God, and that it should simply be abolished, well, that was now a crime.

Tyler MacQueen: And Southern politicians weren’t content with only censoring abolitionists below the Mason-Dixon. In 1835, when the Gag Rule was passed into Congress, Vice President John C. Calhoun proposed a Senate Bill prohibiting the post office from receiving, mailing, or delivering all publications on the subject of slavery.

Jacob Mchangama:Pamphlets were being circulated. So, you have to think of the postal service as sort of the Internet of the day. So, if you wanted – if you were living in New York and you wanted to reach a Southern audience, you’d write a pamphlet, and you’d mail it to the South. And so, Southerners wanted to stop that. They wanted an obligation for postmasters to stop the circulation of abolitionists' writing and materials to the South.

Tyler MacQueen: Outside of legislative halls, abolitionists had to defend themselves often against mob violence. In Illinois, Elijah Lovejoy, the editor of the antislavery paper Alton Observer, died trying to fend off a mob hell-bent on destroying his printing press. In Cincinnati, a proslavery mob destroyed the press of the newspaper Philanthropist. Burnt a week’s run of its papers and then went after its owner. These acts of mob violence across the country turned even the most vehement anti-abolitionist Northerners into abolitionists nearly overnight.

Damon Root: Free speech is like an origin story for several really important figures in the antislavery fight. So one example is Garrett Smith, who is a wealthy New York State landowner. And he’s a major philanthropist supporting abolitionism. He supports William Lloyd Garrison. He’s supports Frederick Douglass. Financially backs Douglass when Douglass strikes out on his own and starts the North Star, his first newspaper. Garrett Smith’s involvement in the formation of the Liberty Party, an abolitionist political party. And Garrett Smith is an ideas man himself also. And Smith, he’s antislavery but kind of a moderate, you would say. And then, he attends in Utica, New York, an antislavery convention. He’s not a member.

He’s just kind of an interested citizen who attends. And this proslavery mob breaks it up. I mean, they’re shouting down the speakers. They’re attacking people. This sort of mob violence to silence abolitionist voices. And Garrett Smith is basically radicalized by this. He becomes a radical abolitionist in response to this. So, he invites everybody back to Peterboro, New York, about 30 or so miles away, where he lives.

And he says, “You come to Peterboro. I’m gonna host this convention. And people are gonna be able to speak freely. We’re gonna have free discussion of slavery.” And he gives this rousing speech there where he talks about how slavery cannot survive prediscussion of it. So, you see this sort of again and again. And just one more example of that is the great Ohio antislavery lawyer Salmon P. Chase, future Chief Justice of the United States. He was sort of moderating antislavery. And there were these mobs in Ohio literally trying to destroy the printing presses of the abolitionist publishers. And he threw himself into the fight.

Tyler MacQueen: To the East and Philadelphia, Angelina Grimke was heckled and pelleted with stones while speaking at the newly opened Pennsylvania hall. In my conversation with Jacob for this episode, he told me Angelina’s story as a female abolitionist in the 19th century and her evolution from the daughter of a plantation owner to one of the most successful abolitionists of her time.

Jacob Mchangama:Angelina Grimke, who was a daughter of a South Carolina slave owner who came to view slavery as basically inconsistent with her strong Christian beliefs. And so, she and her sister toured the North talking about the evils of slavery. So, in 1837 in Massachusetts alone, she spoke at 88 meetings in 67 towns. Reaching an estimated 40,000 people and persuading 20,000 women to sign antislavery petitions. And Grimke became the first woman in America to address a legislative body when she spoke against slavery in the Massachusetts State House in 1838.

Tyler MacQueen: The day after Angelina’s speech, a mob numbering 10,000 people burnt down the newly built Pennsylvania Hall. The police stood silently and did nothing. This was the world that Frederick Douglass escaped to only four months later, on September 3, 1838. He was roughly 21 years of age when he made his escape boarding a northbound train to Baltimore. Under the guidance of a free Black navy officer, Douglass arrived in New York City less than 24 hours later by way of Wilmington and Philadelphia. Finally, he and his wife, Anna, settled down in New Bedford, Massachusetts. It was while living there in Massachusetts that Douglas was introduced to abolitionist thinkers, such as his political mentor William Lloyd Garrison. Perhaps the most famous abolitionist of his time, Garrison was also among the most notorious. Prickly, domineering, and unliked even by his closest friends and allies, Garrison called for unconditional emancipation, even at the cost of the Union itself. In his words, it was a contract with the devil and an agreement from hell.

Lucas Morel: William Lloyd Garrison, I think, was the most famous abolitionist in the United States, if not the world. And he came to fame as an editor of a newspaper called the Liberator, which had a lot of mottos and slogans in the header. But the most famous or infamous one is No Union with Slave Holders.

Tyler MacQueen: This is Lucas Morei, the John K. Boardman, Jr. Professor of Politics and the Head of the Politics Department at Washington and Lee University.

Lucas Morel: Because he was a passivist, he thought that the only way to produce moral reform, and in this case, the peak of moral reform is abolishing slavery immediately in the United States, was that you could only use words. You could only speak or write to produce conviction in the heart of someone who is doing wrong. And in this case, the slaveholder. And so, by publishing his paper, The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison was trying to affect a change in public opinion with regard to slavery in the United States. Frederick Douglass, the most famous man to escape slavery, he bought into this idea that you could only produce abolition through the use of words speaking and writing them. And as you well know, anyone who reads anything by Frederick Douglass recognizes that that guy very soon became a master of what we fondly refer to as the King’s English. Later in his career, he’ll be known as Old Man Eloquent, and it’s because of his use of words. So, in short, Garrison was Douglass’s mentor. And unfortunately, over time, Douglass felt constrained by his mentor and White abolitionists in particular, who were organizing these speaking tours because they wanted him simply to bear witness to the harms of slavery rather than make arguments in his own, from his own soul, and his own mind with regards to the evils of slavery. They just wanted him to talk about life on the plantation, as it were. And it was hard for him because he wanted to speak the King’s English.

And they wanted him to sound more like someone, if you will, fresh off the plantation.

Tyler MacQueen: At first, Douglass agreed with Garrison’s assessment that the Constitution was inherently proslavery. But as time progressed, Douglass’s views on the matter changed. In a speech titled, What to the Slave is the Fourth of July, Douglass publicly refuted his mentor's radical Anti-Constitution sentiments. The Constitution was not antislavery.

Fredrick Douglass: And that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing. But interpreted as it ought to be interpreted. The Constitution is a glorious liberty document. Read its preamble. Consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? Or is it in the temple? It is neither.

Lucas Morel: And he breaks with William Lloyd Garrison over this. Very publicly, very bitterly, Garrison calls him basically a sellout. Says you’re only doing this because you’ve taken Garrett Smith’s money, all of these really nasty charges. Douglass had been – these guys had – they risked life and lived together. They shared the stage. They shared these humble lodging on the road, all these things. And he’s hurt. He’s deeply hurt by these attacks. But at the same time, he grabbles with these ideas. He comes to his own conclusions. He says, “This is what I believe.” The idea that anybody is sort of questioning his integrity is really laughable to me.

And Garrison really comes across poorly in that exchange. Garrison is very admirable, is a heroic figure in American history in many ways. You can’t downplay his contributions, but, boy, he’s not looking too good in this break with Douglass at all. And then, by the time of the Civil War, Garrison essentially comes around to the Douglass point of view. Suddenly, he’s kind of supporting the war effort and all these things. His views change. And so, yeah, it’s a very nasty break between the two of them, but Douglas doesn’t look back. He’s on this new path. The Constitution is a weapon. It’s a glorious liberty document, and let’s use it to fight slavery.

Tyler MacQueen: Douglass’s newfound ideological liberation propelled him to the front of the abolitionist movement. Riding and speaking with great success on both sides of the Atlantic. To Douglass, as it was to the countless abolitionists who came before him, free speech was the most effective weapon in the crusade to end slavery. In an 1854 speech regarding the proposed Kansas-Nebraska Act, Douglass reminded his friends and enemies alike why free speech matters in a Democratic society.

Frederick Douglass: To utter one grown or scream for freedom in the presence of the Southern advocate is to bring down the frightful lash upon their quivering flesh. I knew those suffering people. I am acquainted with their sorrows. I am one with them in experience. I have felt the lash of the slave driver and stand up here with all the bitter recollections of its horrors vividly upon me. There are special reasons, therefore, why I should speak and speak freely. The right of speech is a very precious one, especially to the oppressed.

Tyler MacQueen: To Douglass, the right to free speech was essential not for those in power but for those who were not. If the enslaved could not speak for themselves, then Frederick Douglass would speak for them. And he did so for decades as the sectional tensions continued to rise.

Lucas Morel: He believed that freedom of speech was the most important freedom in order to maintain one’s liberty. He argued that when you read the founders, you’ll find that that was important to them. And again, freedom of speech for him is tied to freedom of assembly. That is to say, the right of the people peaceably to assemble. Right? He doesn’t want an assembly that becomes a mob. Again, an assembly that becomes a mob undermines the whole purpose of freedom of speech. For him, freedom of speech is an expression of the freedom of the human mind. And if the mind is free to think, that is a mind that is free to improve its thinking. It is a mind that is free to, if you will, consider diversity of opinions and expressions of thought. And that’s when as a human being under the right conditions, right, not under a mob situation, but in a peaceful conversation with one’s neighbor or group of neighbors, again, as long as it’s peaceably a peaceable assembly, the freedom to change one’s mind to move from your opinion about something to true knowledge of the thing.

A consideration of all views and then determining which views are better than others. More prudent than others, wiser than others. For Douglass, that was what he called the great moral renovator of a society. This is how you improve that, even if you’ve made gains in your liberty. You can always make war.

Tyler MacQueen: On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln made history when he was elected the nation’s first Republican president, an antislavery politician. Lincoln won only 40% of the popular vote and was not even included on the ballot in most Southern states. Fearing that the institution of slavery was on the road to extinction. South Carolina and several other Southern states declared their intention to secede from the Union. It was a time of great peril for the nation. It was in this political climate that Frederick Douglass and a group of fellow abolitionists met at the Tremont Temple Baptist Church in Boston on December 3, 1860. It was the one-year anniversary of the death of John Brown, whose attempted slave insurrection at Harpers Ferry, Maryland, threw the nation into a panic. The topic of discussion that evening was how can slavery be abolished. Douglass’s small abolitionist gathering was greeted by a violent mob, which took the stage and shouted down the meeting. The city’s mayor and police department stood by and did nothing. Six days later, on December 9th, Douglass delivered a lecture at Boston’s Music Hall.

And before adjourning for the evening, it ended with an impassioned oratory on the free exchange of ideas. It might be the most important defense of free speech in American history.

Frederick Douglass: Even in Boston, the moral atmosphere is dark and heavy. The principles of human liberty, even if correctly apprehended, find but limited support in this hour of trial. The world moves slowly. And Boston is much like the world. We thought the principle of free speech was accomplished fact. Here, if nowhere else, we thought the right of the people to assemble and to express their opinion was secure. But here we are today, contending for what we thought we gained years ago. The mortifying and disgraceful fact stares us in the face that both Faneuil Hall and Bunker Hill monuments stand freedom of speech is struck down. No lengthy detail of facts is needed. They’re already notorious. Far more so than will be wished 10 years hence.

No right was deemed by the fathers of the government more sacred than the right of speech. It was in their eyes as in the eyes of all thoughtful men, the great moral renovator of society and government. Daniel Webster called a homebred right, a fireside privilege. Liberty is meaningless where the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist. That of all rights is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power. Thrones, dominions, principalities, and powers founded an injustice, and wrong are sure to tremble if men are allowed to reason of righteousness, temperance, and of a judgment to come in their presence. Slavery cannot tolerate free speech. Five years of its exercise would banish the auction block and break every chain in the South. They will have none of it there, for they have the power, but shall be so here?

There can be no right of speech where any man, however lifted up or however humble, however young or however old, is overawed by force and compiled to suppress his honest sentiments. Equally clear is the right to hear. To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker. It is just as criminal to rob a man of his right to speak and hear as it would be to rob him of his money. I have no doubt that Boston will vindicate this right. But in order to do so, there must be no concessions to the enemy. When a man is allowed to speak because he is rich and powerful, it aggravates the crime of denying the right to the poor and humble. The principle must rest upon its proper basis. And until the right is accorded to the humblest as freely as to most exalted citizen, the government of Boston is but an empty name. And it’s freedom, a mockery.

A man’s right to speak does not depend upon where he was born or upon his color. The simple quality of manhood is the solid basis of the right. And there, let it rest forever.

Tyler MacQueen: Slavery cannot tolerate freedom of speech because it will produce greater freedom. The height or the noblest expression of freedom of speech is political speech. It is an appeal to the public mind. It is an appeal to the reason of fellow citizens so that by collective deliberation that, yes, we’ll involve diversity of viewpoints, disagreements, maybe even heated arguments, but not blows, physical, not fisticuffs. But the whole point of speaking is so that one could be heard to the point of persuasion. And that’s why we know now, “Oh, that’s we’re against self-censorship.” The intimidation that leads to that. That’s why we’re against the heckler's veto. We’re not against protests. After all, protest is precisely the pinnacle of free speech when authoritative opinion, the opinion held by those who are already in power, is wrong. Or at least there is a perception among the ruled that they’re not doing things in their best interest, and perhaps a different way should be the rule of law.

We are entirely in favor. If you’re in favor of free speech, yes, you’re also in favor of protests. But the protests cannot take the form of mobs appearing, crowds appearing at a scheduled speaker’s talk to shout that speaker down. To shout a speaker down is not an appeal to reason. It is an appeal of intimidation. It’s an expression of intimidation. It is verbal bullying. It is cowing someone. It is not persuading him or her. It is compelling him to stop talking so that only one opinion is expressed. It actually privileges the opinion of the mob.

It is the direct opposite of reason.

Damon Root: Douglass’s plea for free speech was meant not just for the people of Boston. It was for the whole nation. Broken and fragile as it was. Delivered then to a few. His warning about the importance of free speech in a Democratic society has become an example for us all to look to, learn from, and aspire towards. His remarks came in the twilight of antebellum America, where free speech and the free press were routinely censored by powerful Southerners who wished to squash any sentiment of freedom for the enslaved. Less than two weeks after Douglass’s speech, South Carolina would secede from the Union. Ten other states would follow in the coming months. And the battle for human freedom would step out behind the lectern and the printing press and into the farmlands and forests of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Georgia. For many, civil liberties would become a casualty of the American Civil War.

Music: Swing low, sweet chariot.

Tyler MacQueen: As we’ve discovered throughout this episode, free speech and the free press were essential tools in the abolitionist campaign. When met with censorship, the likes of Fredrick Douglass, John Quincy Adams, Angelina Grimke, and Lysander Spooner repelled with greater, more impassioned, and more effective speech. In this era of political tension, the greatest weapons and the struggle to build a more perfect Union were not bullets or bayonets but novels, pamphlets, newspapers, petitions, and the impassioned words of those standing up for the freedom of others. The abolitionists' struggle and their use of free speech to conquer oppression reminds us all that the story of America is the story of one people with many voices.

Freedom of assembly is the right of individuals to come together to express shared ideas, and it is one of the rights expressly guaranteed by the First Amendment. If your rights were violated, contact FIRE today.