Table of Contents

The Trials of Lenny Bruce: The Fall and Rise of an American Icon

Research & Learn

The life, trials, and legacy of a man whom George Carlin said "opened the doors for all the guys like me," and in so doing, became a martyr for free speech in comedy and art.

Lenny Bruce Trial Transcripts and Other Related Documents

Introduction

by Ronald K.L. Collins & David M. Skover

(authors of The Trials of Lenny Bruce)

Comedy respects no one. It is irreverent to Athenian philosophers, Elizabethan kings, French emperors, American statesmen, and even such holy figures as Saint Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Sometimes comedy is poetic, other times farcical, and still other times shamelessly vulgar.

Moving along the spectrum from sauciness and scandal to sacrilege and sedition, comedy mocks everything in its path. Of course, the laugh may be on us when we chuckle over our own foibles highlighted by the comedian on stage. And then consider satire and irony, or parody and burlesque. They all have been wielded over the ages to mock the mighty or to devalue their imperious imperatives.

It is a given: Comedy takes liberties. As such, it depends on liberty to survive. Absent that symbiotic relationship, comedy would collapse into tragedy. When Aristophanes poked fun at the warmongers of his times in his Lysistrata (411 B.C.), he did more than provide grist for a rib-tickling romp. He was, among other things, suggesting that no real Athenian men could end the ceaseless mayhem and squander of young lives. That sort of thing stands to offend those who wage war, those who govern the polity.

This concern with liberty-taking and truth-saying brings us to the role of law in regulating comedy, but that is only part of the reason why the law intervenes to end the laughter and punish the comedian—in this case the famous and infamous Lenny Bruce (1925–1966).

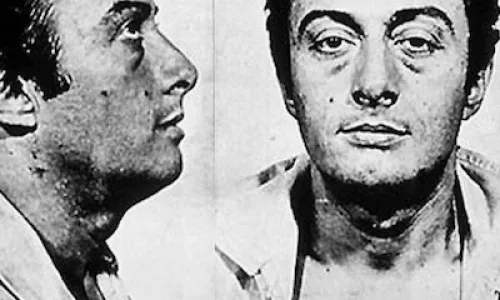

So who was Lenny Bruce? He was the most controversial comedian of his day, the man who single-handedly changed the very architecture of American comedy. He dared to speak the unspeakable. His M.O. was to reveal the hypocrisies that lay at the base of establishment mores.

His mission: to expose “the lie” about words and to free them from social taboos. “Respectability means under the covers. . . . That’s what it means,” is how he once put it. And through his satirical comedy, Lenny Bruce intended to rip the covers off and expose the naked truth about religious hypocrisy, political corruption, race relations, sex, drug use, and homosexuality — all topics that other comedians of his day never dared to touch or address as openly, brazenly, and authentically.

It was in nightclubs that he launched a radical change in comedy. Lenny bounced from one idea to the next—everything from frivolity to raunch, from Yiddish spritzes to jazz jive, from biting satire to philosophical reflection. In all of this, one of his favorite devices was to give public voice to offensive words. Repeating them again and again, he hoped to defuse their power to shock, wound, or paralyze.

When you bust taboos and slaughter sacred cows, you invite trouble. So, between 1961 and 1964, prosecutors in San Francisco (Jazz Workshop), Los Angeles (Troubadour), Chicago (Gate of Horn), and New York (Café Au Go Go) — four of the most culturally sophisticated cities in America in the early 1960s — went after Lenny for word crimes. And they didn’t let the First Amendment stand in their way. It was at that juncture, and for that reason, that we discover in the Lenny Bruce story the presence of some of the most skilled First Amendment lawyers and scholars who sided with Bruce, not necessarily because they agreed with his message, but rather because they defended his right to deliver that message.

The legacy of People v. Bruce is unparalleled in the history of American law. When it was over, really over, the prosecution of Lenny Bruce for misdemeanor obscenity:

- involved at least eight obscenity arrests (for Bruce alone);

- entailed six trials in four cities;

- took some four years and some 3,500 pages of trial transcripts;

- required eight state trial judges (not including the numerous judges who heard bail matters and preliminary motions, etc.);

- engaged more than a dozen state attorneys and double that number of billable- hour defense lawyers;

- prompted legal actions by Bruce in federal courts in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco;

- consumed untold man-hours and amounts of public monies; and

- comprised appeals and/or petitions to state high courts, federal appellate courts, and the Supreme Court of the United States (presided over, in total, by 22 state and federal appellate judges).

And this virtually unprecedented exercise of government power—what was it for? The answers are equally bewildering:

- to enforce laws that, even at the time, were constitutionally suspect or unconstitutionally applied in light of then-new Supreme Court free speech rulings;

- to invoke criminal laws in factual situations where it was not entirely clear that prosecution was required;

- to prosecute cases in which the public interest was dubious; and

- to apply the sanctions of criminal law against a cultural dissenter whose work, when taken as a whole, was clearly of a political or social character (though not simply that).

In 2003, a campaign was launched to posthumously pardon Lenny Bruce. A petition was submitted to then-governor George Pataki of New York State asking him to correct the historical record by recognizing that the law then—the law of the First Amendment—should have protected Lenny Bruce had it not been twisted by those who prosecuted him. As we (and our seasoned pro bono attorney Robert Corn-Revere) noted in our petition, a posthumous pardon should be granted because:

- “There is never a wrong time to do the right thing. Admittedly, a posthumous pardon by definition cannot alter the plight of a deceased person. In that narrow sense, such a pardon comes too late to save a living person from the acknowledged wrongs of the State. Nonetheless, a posthumous pardon does have other salutary and socially beneficial effects.”

- “It corrects the institutional record by publicly expunging the guilt associated with the unlawful or unconstitutional actions of the State.”

Ultimately, Lenny Bruce was vindicated in principle, if not always in practice. However coarse his performances, however brazen his actions in court, and however bizarre his life, the fact remains that his speech was permissible as a matter of law. First, in San Francisco, a jury acquitted him. Second, in Los Angeles, no jury was able to convict him — the charges were either dropped or dismissed. Third, in Illinois, the state supreme court reversed his conviction. And fourth, in New York, the state appellate courts finally sustained the principle of his free speech claims, though not in his case or his lifetime. The tragedy, of course, is that though his speech was legal, Bruce died a convicted man. In the formal annals of recorded law, then, he seemed destined to remain a criminal.

On Dec. 23, 2003 (37 years after Bruce’s death), Governor Pataki granted our petition for a posthumous pardon.

It is remarkable: Aug. 3, 1966 — the date of Lenny’s death — marked a turning point in this nation’s First Amendment history. America’s most controversial comedian struggled for the freedom not only to say what he wanted, but also to say it the way he wanted. He was denied that right. Still, the law eventually vindicated the principle for which he fought. Lenny liberated nightclubs by turning them into America’s freest free speech zones.

Because of the Lenny Bruce saga, comedians — figures such as George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Chris Rock, Robin Williams, Bill Maher, and Margaret Cho — are able to speak authentically without fear of arrest. Not long ago, the young Margaret Cho reflected profoundly on Lenny’s importance for comedians today and her own connection to him. “I don’t want to end up like [Bruce], but I want to be like him.” No doubt, those words capture the sentiment of many a modern-day comedian.

After his death, Lenny’s status as a cultural icon rose to unimagined heights. Death became his greatest publicity agent. Though he died penniless, Bruce made it big. There were books, magazines, articles, documentaries, plays, records, posters, tributes, and even copyright and trademark lawsuits. And in 2016, a documentary entitled Can We Take a Joke? was released; it featured Lenny Bruce in the context of what happens when comedy, hypersensitivity, and political correctness collide on and off college campuses. His legacy thus lives on.

And what of the man behind that legacy? Well, whatever Lenny Bruce’s failings (and he had many), he was not without courage. In a real sense, he embodied the First Amendment. Bruce was not afraid to speak his mind by the light of his own truth and with the force of his own voice. The truth he spoke was often unpleasant, and what he uncovered disturbed those who would silence him. But because Bruce never stopped telling the truth as he saw it — in his own open, robust, and uninhibited manner — he made it possible, as Margaret Cho put it so well, for others to be like him without having to end up like him.

The transcripts available on this site are from Lenny Bruce’s obscenity trials in San Francisco, Los Angeles (Beverly Hills), Chicago, and New York. This is the first time these complete transcripts have been made accessible to the general public and free of charge. We have also posted related materials — including appellate briefs, unpublished judicial orders and opinions, the petition for a posthumous pardon, etc. — to provide a fuller picture of Bruce’s battles with the law. Our hope is that these documents, and others yet to be posted at a later time, will help to tell the Lenny Bruce story as never before told.

Portions of this Introduction were adapted from Collins & Skover's The Trials of Lenny Bruce: The Fall & Rise of an American Icon (Sourcebooks, 2002) and Ronald Collins' Comedy & Liberty: The Life & Legacy of Lenny Bruce, 79 Social Research 61–82 (2012).

Lenny Bruce Trial Transcripts and Other Related Documents

- San Francisco Trial Transcript

- Chicago Trial Transcript, People v. Lenny Bruce

- Order of the Supreme Court of Illinois, July 7, 1964

- Los Angeles Trial Transcript

- San Francisco Trial Minute Order, December 28, 1962

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 1

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 2

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 3

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 4

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 5

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 6

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 7

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 8

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 9

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 10

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 11

- New York Trial Transcript, Volume 12

- Unpublished New York Trial Court Opinion

- Petition for Pardon

- Pardon

Briefs and Related Documents Filed in the Supreme Court of Illinois

- Petitioner's Abstract of Record Admitted to Supreme Court of Illinois 1963

- Brief for Defendant in Error in Supreme Court of Illinois 1963

- Brief of Points and Authorities by Plaintiff in Error, Supreme Court of Illinois 1963

- Brief in Argument for Plaintiff in Error, Supreme Court of Illinois 1963

- Reply Brief for Lenny Bruce in Supreme Court of Illinois 1963

- Suggestions of Illinois Attorney General to Supreme Court of Illinois 1963