Table of Contents

What is the stopping point? Responses to the Supreme Court’s 303 Creative decision — First Amendment News 387

Fred Schilling / Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court as composed June 30, 2022 to present. Front row, left to right: Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., Associate Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., and Associate Justice Elena Kagan. Back row, left to right: Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

Make of what you will of the Court’s recent ruling in 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, but one thing is clear: there is considerable disagreement about its merits and meaning, even among those in the First Amendment community. The ACLU’s David Cole, for example, has described it as “fundamentally misguided.” Larry Tribe maintains that “the case is built on a lie. But the damage it wreaks is all too real.”

And then there’s this:

Allowing 303 Creative to discriminate on the basis of the First Amendment’s protections would necessarily open the door to conflicts between such ‘expressive’ interests and other laws of general application, unsettling the law in multiple ways.

That assertion was made in an amicus brief filed on behalf of the Respondent. Among others, it was signed by Vincent Blasi, Erwin Chemerinsky, Burt Neuborne, Robert Post, and Geoffrey Stone.

My point: for those who argue that the 303 Creative ruling is beyond dispute, take heed! It is far from settled.

The main question to grapple with is this: Is there a stopping point? If so, where . . . and why?

Columbia University law professor Katherine Franke, who also serves as director of the Center for Gender and Sexuality, contends that this case is “a green light for people to engage in what was previously understood as discrimination.”

Is she correct? Or was Kristen Waggoner, the lawyer who successfully argued the case in the high court, correct when she said, “Colorado and a number of media outlets have blatantly misrepresented the facts and the Supreme Court’s decision” in 303 Creative?

What does one make of how Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes characterized the opinion?

[A] woefully misguided majority of the United States Supreme Court has decided that businesses open to the public may, in certain circumstances, discriminate against LGBTQ+ Americans. While my office is still reviewing the decision to determine its effects, I agree with Justice Sotomayor – the idea that the Constitution gives businesses the right to discriminate is “profoundly wrong.”

Even those sympathetic to Justice Gorsuch’s majority opinion, such as Dale Carpenter, are measured in their response.

“I read Justice Gorsuch’s decision as broader in some respects than some may hope it is,” he said. “It can’t reasonably be cabined to all of its specific facts.”

And did Justice Gorsuch not concede as much when he wrote, “Doubtless, determining what qualifies as expressive activity protected by the First Amendment can sometimes raise difficult questions”?

So, where is the stopping point?

When it comes to providing services, are the constitutionally operative words “customized,” “tailored,” or “expressive” sufficient to invoke a First Amendment claim under 303 Creative?

Consider Justice Gorsuch’s admonition in this regard:

[O]ur case is nothing like a typical application of a public accommodations law requiring an ordinary, non-expressive business to serve all customers or consider all applicants. Our decision today does not concern — much less endorse — anything like the “straight couples only” notices the dissent conjures out of thin air.

As Justice Gorsuch noted, Justice Sotomayor and her dissenting colleagues viewed the matter quite differently:

The business argues, and a majority of the Court agrees, that because the business offers services that are customized and expressive, the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment shields the business from a generally applicable law that prohibits discrimination in the sale of publicly available goods and services. That is wrong. Profoundly wrong. . . .[T]he law in question targets conduct, not speech, for regulation, and the act of discrimination has never constituted protected expression under the First Amendment. Our Constitution contains no right to refuse service to a disfavored group.

*** Note: See also the 2023 case of Klein v. Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries, another cake baker case, granted cert., judgment vacated, and remanded to the Oregon Court of Appeals.

What, then, is the practical and legal reach of the Court’s recent 6-3 ruling in 303 Creative? Put another way: What, if any, is the operative free speech principle as applied that governs such cases? Might a claim under the Free Exercise Clause alter the constitutional equation?

Consider the following examples:

- Relying on 303 Creative, a state judge refuses to issue a marriage license to a same-sex couple.

- On First Amendment grounds, a hair stylist refuses to serve certain LGBTQ+ persons.

- A lesbian couple seeks lodging at a roadside motel with no other nearby public accommodations. The owner of the motel refuses them on First Amendment Free Exercise grounds since he believes same-sex relations and marriage are morally wrong.

It’s not reasonable to interpret 303 Creative to allow that salon to engage in discrimination, but these are exactly our long-founded concerns. Not only for the real discrimination that will be permissible as a result of 303 Creative, but that it will inspire discriminatory behavior, and really disgusting public discourse about LGBTQ people.

— Sarah Warbelow, Human Rights Campaign’s legal director

In all of this, certain troubling questions arise: First, when does such discriminatory conduct amount to expression under the First Amendment? In its amicus brief, the national ACLU viewed the governing issue differently: “The relevant question is not whether 303 Creative’s Conduct is expressive . . . but whether the State’s interest in regulating it is related to the suppression of expression.”

Beyond that, does the mere invocation of a free exercise right suffice to justify such discrimination? How are such claims to be judged?

One suggested approach comes from Dale Carpenter’s “How to Read 303 Creative v. Elenis,” in the The Volokh Conspiracy blog:

The speech compulsion it forbids is not limited to wedding-website designers who object to same-sex marriage, but its principles should apply only to a narrow range of commercial products.

[. . .]

[T]he decision is also narrower in important ways than some progressives fear or some religious conservatives/libertarians may hope. I read 303 Creative to hold that a vendor cannot be compelled by the government:

(1) to create customized and expressive products (whether goods or services) that constitute the vendor's own expression . . . ;

(2) where the vendor's objection is to the message contained in the product itself, not to the identity or status of the customer . . .

Related (Standing Issue)

- David Post, “More on Standing in the 303 Creative Case,” The Volokh Conspiracy (July 18)

- David Post, “Case or Controversy Requirement? What Case or Controversy Requirement?” The Volokh Conspiracy (July 8)

Bob Corn-Revere and government pressure on social media platforms to censor

- Robert Corn-Revere, “A Win for the First Amendment, and a Loss for Partisans Who Want to Weaponize Censorship,” Reason (July 16)

On America's birthday, yet another front in the culture war opened over the meaning of free speech.

The provocation? On July 4, a federal court ordered Joe Biden's White House and a bevy of federal agencies and officials not to pressure social media platforms to delete or suppress broad categories of information, including posts on the pandemic, the 2020 election, and Hunter Biden's laptop.

Initial reporting on Judge Terry A. Doughty's 155-page opinion in Missouri v. Biden reflected our polarized times. The Washington Post labeled the decision a “win for the political right" while The New York Times called it "a victory for Republicans.” The headline for the Post story placed quotation marks around the word censorship.

But shouldn't this just be considered a win for the First Amendment and not a partisan matter? After all, most of us should be able to agree it's a bad idea for government officials to huddle in back rooms with corporate honchos to decide which social media posts are "truthful" or “good” while insisting, Wizard of Oz–style, “pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”

Knight Institute challenges Texas TikTok ban

- “Researchers and Knight Institute Challenge Constitutionality of Texas TikTok Ban,” Knight First Amendment Institute (July 13)

The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University filed suit today on behalf of the Coalition for Independent Technology Research asserting that Texas’s TikTok ban, initially imposed by Texas Governor Greg Abbott last year, violates the First Amendment. The ban requires all state agencies, including public universities, to bar employees from downloading or using TikTok on state-owned or -issued devices or networks, as well as on personal devices used to conduct state business. The lawsuit challenges the ban’s application to public university faculty, asserting that it compromises academic freedom and impedes vital research.

“Banning public university faculty from studying and teaching with TikTok is not a sensible or constitutional response to concerns about data-collection and disinformation,” said Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute. “Texas must pursue its objectives with tools that don’t impose such a heavy burden on First Amendment rights. Privacy legislation would be a good place to start.”

The Coalition for Independent Technology Research is a group of academics, journalists, civil society researchers, and community scientists that works to advance, defend, and sustain the right to study the impact of technology on society. The coalition’s members include professors at public universities in Texas whose research and teaching have been compromised by the ban.

Complaint: Coalition for Independent Technology Research. v. Abbot (U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, July 13, 2023)

Forthcoming book on free speech and intellectual diversity in the academy

- James Stoner Jr., Paul O. Carrese, and Carol McNamara, eds., “Free Speech and Intellectual Diversity in Higher Education,” Lexington Books (Sept. 15)

The essays in Free Speech and Intellectual Diversity in Higher Education reflect diverse perspectives on one of the most pressing issues in higher education — the controversies over freedom of speech and its relation to intellectual diversity.

Does the First Amendment apply on campuses and do its principles clarify or obscure the issues surrounding campus speech? What, after all, is the basis for those principles, and how do they relate to the purposes of the university? Is free speech truly effective without a diversity of perspectives, and to what extent is such diversity found at universities today? Does free speech discourage the inclusion of minorities or previously excluded groups?

Are there specific policies that can address the issue of free speech on campuses today in ways that are fair to all parties and to the interests at stake?

- Brian Soucek, “Speech First, Equality Last,” Arizona State Law Journal (2023)

Universities have been put in an impossible situation. They are liable under nondiscrimination laws if they allow hostile speech to interfere with someone’s education, but they are increasingly said to be liable under the Free Speech Clause if they do anything to stop speech before that point. Put simply, universities are liable for acting until the moment when they are liable for not having acted.

This conundrum — what this Article calls the Double Liability Dilemma — is the result of remarkably successful litigation brought in courts across the country by a recently formed, conservative free-speech organization called Speech First. Three courts of appeals, with a fourth perhaps soon to come, have recently enjoined universities from enforcing their harassment policies. These schools now find themselves unable to act to counteract hostile speech based on race or sex before it is too late.

To see the Double Liability Dilemma is to see that these cases simply cannot be rightly decided — and to wonder how courts or commentators might ever think otherwise. Providing the first close look at litigation that is reshaping speech and harassment regulation throughout American higher education, this Article highlights the procedural mechanisms Speech First has used to push courts into taking what critical race theorists have long referred to as the “perpetrator perspective.” By contrast, this Article shows how a broader perspective, taking both sides of the dilemma into account, forces us to rethink the meaning and reach of the First Amendment on college and university campuses.

‘So to Speak’ podcast on free speech during Civil War

- “Civil Liberties and Civil War “(July 13)

In the last episode of the “So to Speak” podcast, we traced the dramatic story of free speech in the United States from colonial America to the abolitionists' campaign to abolish slavery. In this week's episode, we pick up where we left off and explore the complicated history and legacy of civil liberties during the American Civil War.

Professor and author Joseph R. Fornieri and FIRE Chief Counsel Robert Corn-Revere join the show this week to unpack Abraham Lincoln's justifications for suspending civil liberties and the important lesson that, in war, civil liberties can be hard to uphold, and our rights can be difficult to defend.

Institute for Free Speech expands communications team

The Institute for Free Speech is pleased to announce that Sarah Fisher has joined IFS as Associate Director of Communications. Tiffany Donnelly, who joined the Institute as media manager in 2019, has been promoted to Deputy Director of Communications.

Sarah comes to IFS after nearly four years on the communications team for Council for a Strong America, a nonprofit advocacy organization in Washington, DC.

Sarah has wide-ranging public relations and social media experience in the arts, entertainment, and nonprofit sectors. In her career, she has published dozens of pieces in major news outlets across the country and created social media content for audiences of over a million people. She is a graduate of the University of Virginia and resides in Hampton Roads.

Regarding her new position, Sarah said, “I am thrilled to join the Institute for Free Speech team and further elevate the critical work of this organization.”

Sarah and Tiffany will collaborate with the Chief Communications Officer on media outreach, social media, guest commentaries, and more.

Tiffany will continue her role as Editor-in-Chief of the Daily Media Update, a curated compilation of the latest free speech and campaign finance news.

More in the news

- Eugene Volokh, “First Amendment Claim of Professor Fired Over Article Claiming Race-Based Genetic IQ Differences,” The Volokh Conspiracy (July 18)

- Sarah McLaughlin, “UN Human Rights Council gets it wrong: Prosecuting blasphemy won’t stop religious discord, but it will silence dissent,” FIRE (July 18)

- Betsy Hammond, “Oregon senator who threatened ‘hell’s coming to visit you’ wins 1st Amendment case,” The Oregonian (July 18)

- Alex Rose, “Racist flyers appear again in Delaware County, launching First Amendment discussion,” Delaware County Daily Times (July 17)

2022-2023 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Cases decided

- 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis (6-3 per Gorsuch for the majority and Sotomayor for the dissent: The First Amendment prohibits Colorado from forcing a website designer to create expressive designs speaking messages with which the designer disagrees.)

- Counterman v. Colorado (Held: First Amendment violated — 4 votes per Kagan with Sotomayor concurring in part joined by Gorsuch in part. Thomas filed a dissent and Barrett also filed a dissent, in which Thomas joined). (“In this context, a recklessness standard — i.e., a showing that a person ‘consciously disregard[ed] a substantial [and unjustifiable] risk that [his] conduct will cause harm to another’ . . . — is the appropriate mens rea. Requiring purpose or knowledge would make it harder for States to counter true threats — with diminished returns for protected expression. The State prosecuted Counterman in accordance with an objective standard and did not have to show any awareness on Counterman’s part of his statements’ threatening character. That is a violation of the First Amendment.” )

- Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC (9-0: held — When a defendant in a trademark suit uses the mark as a designation of source for its own goods or services — i.e., as a trademark — the threshold Rogers test for trademark infringement claims challenging so-called expressive works, see Rogers v. Grimaldi, does not apply, and the Lanham Act’s exclusion from liability for “[a]ny non-commercial use of a mark” does not shield parody, criticism, or commentary from a claim of trademark dilution. (This from footnote 1 of the majority opinion: “To be clear, when we refer to ‘the Rogers threshold test,’ we mean any threshold First Amendment filter.” Justice Kagan wrote the majority. Justice Sotomayor filed a concurring opinion, in which Justice Alito joined. Justice Gorsuch filed a concurring opinion, in which Justices Thomas and Barrett joined.)

- United States v. Hansen (7-2: Title 8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(A)(iv) — which criminalizes “encouraging or inducing” illegal immigration — forbids only the purposeful solicitation and facilitation of specific acts known to violate federal law and is not unconstitutionally overbroad.)

Review granted

- Vidal v. Elster

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier

- 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis (argued Dec. 5)

- Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC (argued March 22)

- United States v. Hansen (argued, March 27) (Volokh commentary here)

- Counterman v. Colorado (argued, April 19)

Cert. granted and case remanded

- U.S. v. Hernandez-Calvillo (cert. granted, judgment vacated, and case remanded to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit for further consideration in light of United States v. Hansen)

- Klein v. Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries (cert. granted, judgment vacated, and case remanded to the Court of Appeals of Oregon for further consideration in light of 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis).

Pending petitions

- Center for Medical Progress v. National Abortion Federation

- Mazo v. Way

- Tingley v. Ferguson

- Frese v. Formella

- National Rifle Association of America v. Vullo

- Moody v. NetChoice, LLC

- NetChoice, LLC v. Moody

- Florida v. NetChoice

State action

- O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier (cert. granted)

- Lindke v. Freed (cert. granted)

Qualified immunity

- Novak v. City of Parma (cert. denied)

Immunity under Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act

- NSO Group Technologies Limited v. WhatsApp, Inc. (cert. denied)

Liability Anti-Terrorism Act

- Twitter v. Taamneh (held, 9-0 per Thomas, J.: SCOTUSblog: “Plaintiffs’ allegations that the social-media-company defendants aided and abetted ISIS in its terrorist attack on a nightclub in Istanbul, Turkey fail to state a claim under 18 U.S.C. § 2333(d)(2).”)

Section 230 immunity

- Gonzalez v. Google (held, 9-0, per curiam, SCOTUSblog: “The 9th Circuit’s judgment — which held that plaintiffs’ complaint was barred by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act — is vacated, and the case is remanded for reconsideration in light of the court’s decision in Twitter, Inc. v. Taamneh.”)

Review denied

- Mobilize the Message v. Bonta

- North Carolina Sons of Confederate Veterans v. North Carolina Dept. of Transportation

- Price v. Garland

- Keister v. Bell

- Morgan v. Arizona

Previous FAN

FAN 386: “Abandoned love: The left’s move away from the right’s First Amendment”

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE or of Mr. Collins.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

The American people fact-checked their government

Facing mass protests, Iran relies on familiar tools of state violence and internet blackouts

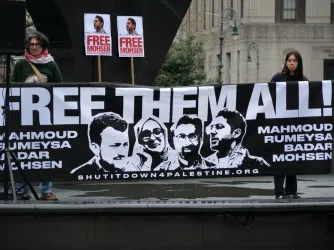

Unsealed records reveal officials targeted Khalil, Ozturk, Mahdawi solely for protected speech