Table of Contents

Happy 150th Anniversary, 14th Amendment

It’s the 150th anniversary of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Without it, there wouldn’t be a FIRE, because there wouldn’t be any rights to protect on campus.

For all the praise that’s heaped on the First Amendment, most of the good it does today is due to the 14th. If you really think about it, the 14th Amendment was the catalyst that finally evolved our experimental form of government into one striving to be worthy of the words of the Declaration of Independence.

I can explain, but to do that, we ought to go back to the beginning. Well, almost the beginning. The second paragraph of the Declaration:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed...

This is a beautiful sentiment, and the ideal to which we continually strive. Unfortunately, when it came time to actually enshrine these in a constitution, the drafters made some compromises. Some really, really ugly compromises.

While the Declaration said all men were created equal, the Constitution enshrined and protected slavery as the law of the land. The Declaration was free to be an unrestrained expression of our highest ideals; the Constitution, on the other hand, required the signatures of state delegates, and some of those states had economies that relied on the institution of slavery.

The Constitution’s preamble talked about a “more perfect” union, sure. But if the drafters wanted the state delegates to agree to any kind of a union, it needed to be a lot less perfect than what they described in the Declaration. After the powers of the government were enumerated in the main body of the document, some state delegates (looking at you, George Mason) felt some rights of the people ought to be enumerated too. The delegates added the Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment.

At the time it was written, its authors didn’t believe that the First Amendment restricted the ability of a state to limit what you could say or publish; as the text states, it restricted the ability of the federal Congress to make laws. For decades after the First Amendment’s passage, states were free to make laws limiting speech or proscribing forms of religious observation as they saw fit. It took over eighty years before the Supreme Court even analyzed any substantive First Amendment question, and in that case, it upheld the federal government’s power to outlaw bigamy.

It was the aftermath of the Civil War that pushed us to re-examine the scope of these guarantees. In the first few years after the war’s end in 1865, some state legislatures in former Confederate states worked to limit the freedom granted to once-enslaved Americans. Congress responded by passing a new civil rights law and three constitutional Amendments: the 13th, 14th, and 15th. The 13th abolishes slavery; the 15th prohibits abridging the right to vote on the basis of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The 14th Amendment was a bit more complicated than the other two, and its first section — the one that’s most important to First Amendment advocates — purports to announce a number of changes in how civil rights work. The parts that would end up being most important today, in plain language, say:

- Anyone born or naturalized in a state is a citizen of that state.

- No state can deprive anyone of “life, liberty, or property” without “due process of law;” and

- No state can deny any person the “equal protection” of the laws.

It wasn’t really clear how these promises of due process and equal protection were going to work until 1925, when the Supreme Court finally held that the promise of freedom of speech was so important that it was “incorporated” into the rights promised under the 14th Amendment. In the years since, nearly every right granted by the Bill of Rights has been “incorporated” and made to apply as a limit on the power of the states.

Eventually, the Supreme Court would be asked to confront these rights in the context of state education directly. In 1943, the Court found that public schools must respect the religious freedom of their students. In 1954, the Court found that students had a right to the equal protection of the laws. And in 1969, the Court found that schools had to respect the right of freedom of expression in schools, provided the expression was non-disruptive.

Without those rulings, there wouldn’t be any rights under the U.S. Constitution to protect on campus, as universities and colleges are largely state, not federal, institutions. And those rulings only exist because of the 14th Amendment.

A student of history might well be surprised to see what became of the Constitution after the 14th Amendment. Our delegates and founders agreed to a federal government that would stand back and permit states to limit civil rights; instead, today, we have a federal government that defends (actively, when necessary) the constitutional rights of its citizens.

I instead prefer to see it as the union ever-evolving into a more perfect form. When we declared our independence, we said that all men (really, all persons) are created equal and have “unalienable rights,” including the right to liberty. Our Constitution did not live up to that promise. It may never fully attain it. But we are far closer today because of the 14th Amendment.

So happy anniversary, 14th Amendment. May your next 150 years bring us ever closer to our ideals.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

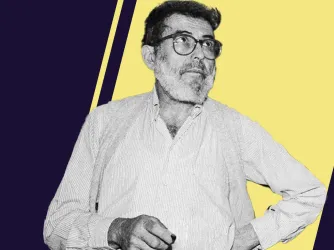

Remembering 'free-thinking' writer Nat Hentoff

Podcast

FIRE's 2025 impact in court, on campus, and in our culture

VICTORY: Court vindicates professor investigated for parodying university’s ‘land acknowledgment’ on syllabus