Table of Contents

University of New Hampshire’s removal of anti-sexual harassment exhibit undermines free speech

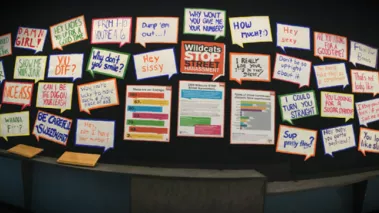

via The New Hampshire, which posted the photo courtesy of Connie DiSanto.

FIRE and others are asking questions about the University of New Hampshire’s decision to remove a student-led exhibit criticizing street harassment and allow it to be re-posted only after making changes apparently acceptable to administrators’ tastes about what language is sufficiently inoffensive to be shared on a university campus.

Student Jordyn Haime came up with the idea for the exhibit and worked with the university’s Sexual Harassment & Rape Prevention Program (SHARPP) to send a survey to students about their experiences with street harassment. After gathering the results, Haime created an exhibit incorporating the information gathered.

The exhibit, displayed on the third floor of the university’s Memorial Union Building, contained statistics from the survey and quotes from students’ experiences with street harassment, including “You look like sluts,” “I’ll buy you a drink if you suck me off,” “Flash your boobs,” and more. According to SHARPP, one of its members informed the building’s staff about the exhibit’s concept before it was displayed. Haime and SHARPP also said they chose to display “milder” statements gathered from the survey.

The exhibit, which was intended to stay up throughout April — which is Sexual Assault Awareness Month — was removed within hours after it was posted on March 17. The exhibit was replaced with a display praising students’ contributions to the community.

According to the university’s American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and Lecturers United-AAUP chapters, the University of New Hampshire justified the exhibit’s removal under section 8.03 of the building’s posting policy. The policy states in part, “Any poster with ‘hate speech’ as defined in the Student Rights, Rules and Responsibilities will not be posted. Any poster/flyer containing profane/vulgar language is prohibited.” A report by WMUR, the ABC affiliate in Manchester, also quotes a university spokeswoman citing this prohibition. Haime and SHARPP said they were not made aware of this policy when they proposed the exhibit.

According to a Friday report, the university has agreed to allow a modified version of the exhibit to “eventually” return to its original location inside the Memorial Union Building, but only after Dean of Students Ted Kirkpatrick “circled comments [on a photo of the display] that could be included in the revised version.” Haime is, according to the report, not satisfied with this result — and understandably so, as it still results in administrative censorship of her project.

In a comment to The New Hampshire, Kirkpatrick discussed his rationale for removing exhibit, pulling the “we believe in free speech, but” card and claiming that viewers’ reaction to the exhibit justified its removal:

“Put another way, while I am certain that this was not the intent of the display, the fact is that the display elicited strong negative reactions from some who saw it,” Kirkpatrick said. “Importantly, the university does not shrink from its loyalty to the principle of free speech but the university does ask members of its community to respect a sense of decorum and civility in order that heated debate about important and pressing issues may obtain.”

Apparently, it is not in line with “a sense of decorum and civility” for a student to repeat words that students claim have been said to them, as a means of sharing their concerns.

But Kirkpatrick wasn’t quite done with recycling tired excuses for censorship. He also deployed the ol’ “think of the children!” rationale:

Additionally, open house season for admitted students and their families began last week and, according to Kirkpatrick, some of the “language used on the [Memorial Union Building] wall placards was not suitable for young children or for those members of our publics and our campus community who have strong personal convictions that may originate from religious, spiritual or ethnic roots.”

FIRE has heard these excuses — “think of the children,” “hate speech,” “free speech, but” — innumerable times. They’re never compelling, rarely coherent, and almost universally an excuse for censoring unpopular expression. And that’s why we’re writing to the university this week to ask why these unconvincing excuses are being summoned to justify the removal of an exhibit created by a student working with a university-led program.

It’s understandable that, as Kirkpatrick says, “the display elicited strong negative reactions from some who saw it.” The messages displayed in the exhibit were arguably crude and could make for uncomfortable reading. And that was the entire point. Haime and SHARPP intended to make it difficult for people to ignore the comments they say students have faced while walking in the street. As Haime explained to The New Hampshire, “These are real things said by students… [SHARPP] is trying to [provide] a platform so the voices [of those who have experienced street harassment] can be heard and we can start a discussion about it.”

As we’ve stated before, a viewer’s negative reaction to material that offends them is not a valid reason to censor that material. My colleague Adam Steinbaugh explained last month that offense is often the response artists hope to elicit from their work, not an unintentional byproduct:

Drawing attention to views in order to criticize them is a time-honored tradition. Repurposing offensive or shocking imagery as a means of exposing perceived atrocities or bigotry is an important way to convey the moral urgency of one’s cause, if not demonstrate its very existence. Efforts to silence speech because it is offensive risk chilling, if not foreclosing, this critical channel of communication.

Haime explained this position further in an op-ed defending the exhibit:

To counter the administration’s arguments, I would say that offense is the appropriate response to the quotes on the wall. Our display contained real things that had been said to students on this campus, and yes, they were horrible. That fact should upset people and cause them to want to take action on the issue, like we did. We did not pull these quotes from the internet for shock value, we pulled them from a survey that we conducted and that UNH students answered. Words like “boobs” and “suck” are not horribly vulgar or profane and the response from the administration was uncalled for. I do not believe I did anything offensive or controversial; my intention was to spark dialogue on an important topic that has not been addressed on this campus, but the issue can never be mended or even discussed if it is hidden.

In its statement supporting Haime, Stop Street Harassment, a nonprofit group that documents street harassment, made a similar argument as well:

If people were offended by reading the street harassment stories, imagine what the person who was targeted felt when she or he experienced it first-hand. How can we work to stop these comments from being spoken if we try to hide that they are said at all? Instead of censoring campaigns to raise awareness about street harassment — an issue that, as Ms. Haime says, she and others normally regard as something that “just happened to them” — the administration should celebrate one of its student’s efforts to bring attention to such an important issue.

Street harassment is offensive. It is deplorable. It is uncomfortable. It can cause real emotional harm and even pose health risks when it’s extreme and/or repeated. It is a human rights violation and a form of gender-based violence. But this does not mean we should ignore it or that it is too controversial to discuss.

Most of what people call “hate speech” is protected by the First Amendment — for good reason — and the controversy over the university’s removal of this anti-sexual harassment exhibit is a perfect example of the importance of that protection. A policy against “hate speech” and “vulgar language,” neither of which are categories of speech unprotected by the First Amendment, was used to silence students’ criticism of the very words used against them. This should serve as a reminder to all students that policies that many believe are meant to combat injustice could be used to perpetuate it.

Stay tuned for FIRE’s letter and further updates on the story.

Update (April 7, 2017): FIRE has now written to the University of New Hampshire. Our letter is here.

Recent Articles

Get the latest free speech news and analysis from FIRE.

Princeton president misunderstands FIRE data — and campus free speech

The global free speech recession

What I told the Senate Commerce Committee about 'jawboning'